Cadence hosted a panel at DAC on how EDA, MCAD and industrial software have come together, a topic I always find interesting. Many years ago, I worked on a NAVAIR contract bid team, an eye-opener for a young engineer who thought that innovation started and ended with electronic design. I remember CATIA (3D modeling) being a component in the bid, along with PLM and other automation outside the EDA realm. This naturally made me wonder about the interaction between these domains. Back then, there wasn’t much interaction that I remember. This panel provided a useful update on what has changed.

The panel was moderated by Jay Vleeschhouwer (Managing Director at Griffin Securities) and included John Lee (GM/VP of the Electronics, Semiconductor and Optics Business Unit at Ansys), Tom Beckley (Sr. VP/GM of the Custom IC and PCB Group at Cadence), Brian Thompson (Division VP/GM of CREO and Desktop Engineering Calculations at PTC), Stephane Sireau (VP of High Tech Industry for Dassault Systèmes), and Tony Hemmelgarn (President and CEO of Siemens Digital Industries Software). These executives represent a comprehensive span of automation and lifecycle management across systems design. In some areas, each offers unique advantages, in others they compete, sometimes they cooperate. As usual in my panel write-ups, I’ll summarize my takeaways.

What motivates convergence?

Back in my NAVAIR days the boundaries between electrical CAD, mechanical CAD, and software were pretty sharp. Physics analytics and lifecycle management were system concerns: Screening, decoupling, cooling outside the chip, making sure that thermal, ESD, EM, and aging fell within pre-agreed limits. Now boundaries are more diffuse with more complex application-specific SoCs and sensing in faster and more challenging processes, smaller enclosures complicating thermal management, tighter coupling between mechanical and electrical, stronger constraints on aging and operation in hostile environments, plus, of course, security and safety.

Tighter coupling leads to more interdependence in the design of the whole system. Failing to meet a requirement can have broader consequences, triggering a respin in silicon, multi-die systems, enclosures, mechanical design, or in software. Active lifecycle management is becoming more important for remote devices, in predictive maintenance applications, or where safety critical automation in automotive and aerospace applications must be checked frequently and should fail gracefully if a problem is detected.

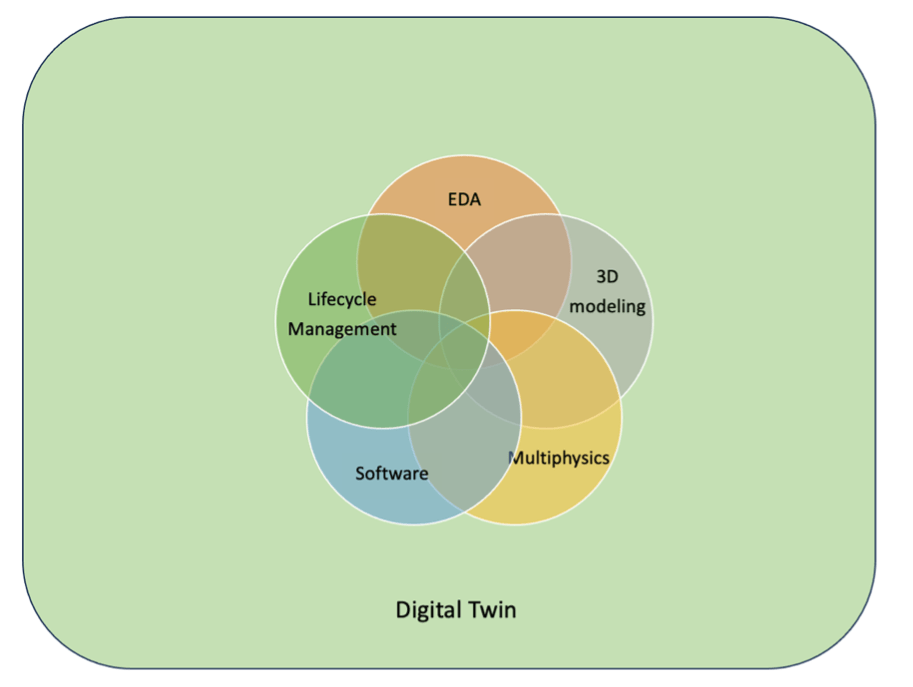

Digital twins

Everyone endorsed digital twins to characterize and refine the complete system model before committing to manufacturing, seeing this as a better way to co-optimize each of these domains with quick turnaround and at much lower cost than doing the real thing. What a twin will look like depends very much on the domain. A twin for an assembly line or a jet fighter will necessarily have significant emphasis on mechanical content, supported by electronic enhancements. A twin for a data center or a fixed wireless access network would be more electronics-forward, with some mechanical support (cooling, for example).

Curiously, automotive is still figuring out which side of this divide it wants to be on. According to Alberto Sangiovanni-Vincentelli, who gave an earlier keynote, Tesla takes the view that they are fundamentally an electrical engineering and software engineering company. They start in electronic system architecture and then weave in the rest of the system, mechanical, etc., iterating to deliver the highest performance they can. In contrast, a traditional automotive OEM starts where they have always started—volume manufacturing and mechanical engineering. But, when they assemble electronics into the chassis, they blow their power envelope —at least compared to Tesla. This question of system design with electronics-forward or mechanical-/manufacturing-forward may be important not only here but in all systems where electronic content is rising rapidly.

Partnerships and coopetition

Clearly each of the panelists’ organizations have their own core strengths yet tread on each other’s turf in one way or another: Multiphysics, CFD, PLM, digital twins, 3D modeling, etc. This isn’t so unusual, especially in mechanical and industrial software. Customers want best in class solutions, as always. Vendors respond preferentially through organic growth or acquisitions (ex., the Siemens acquisition of Mentor Graphics). Siemens has their own MCAD and PLM offerings; Dassault and PTC are also established in those domains but do not have EDA capability or certain multiphysics options in-house so must rely on partnerships. However, none of them can cover all the bases. Even Siemens EDA (Mentor) must be augmented in several areas.

Conversely Cadence, which was historically concerned primarily with semiconductor design, now offers tightly integrated capabilities analytics and design capabilities around package and board assembly to ensure comprehensive solutions for design, electromagnetics, power distribution, EM, thermal and cooling. The Cadence focus on computational software drives in-house capabilities like CFD and datacenter energy optimization and, in a different direction, molecular simulation. Ansys, on the other hand, is squarely focused on what they call pervasive insights through multiphysics analysis as a capability you can call from anywhere, not only in the electronics domain.

All agreed that partnerships are essential to meet customer expectations, and that those partnerships consume a lot of energy. They must draw clear boundaries on where they compete and where they cooperate. Interestingly, difficulties are mostly in field and distributor organizations where alignment demands much more up-front and ongoing effort. At the technical level, multiple methods were suggested to simplify handshaking between tools.

Ansys has released a Python-compatible open-source version of all their APIs to GitHub. Linking clouds is another popular approach, particularly because speakers felt it easier to standardize and maintain interfaces in a cloud environment (where I assume versions and features are more easily controlled) than in on-premises platforms. Collaboration still depends on either standardized or de-facto standard interfaces; no one saw value in “universal” standards across such a diverse range of design domains.

One last thought here. Simulation Process and Data Management (SPDM) came up a few times in this discussion with regard to tracing digital threads across all simulation domains: Requirements, digital twins, test, model-based system engineering (MBSE) and verification management. I can’t find anything on the subject in core EDA; however, I do see Ansys and others making noise on the value of SPDM in complex system design. It will be interesting to see if this topic starts to appear in EDA also!

Very enlightening discussion on a topic of growing importance.

Share this post via:

Comments

One Reply to “Convergence Between EDA and MCAD and Industrial Software”

You must register or log in to view/post comments.