Despite murky goals and moving targets, the recent CHIPS Act sets the stage for long term government incentives.

Authored by Jo Levy and Kaden Chaung

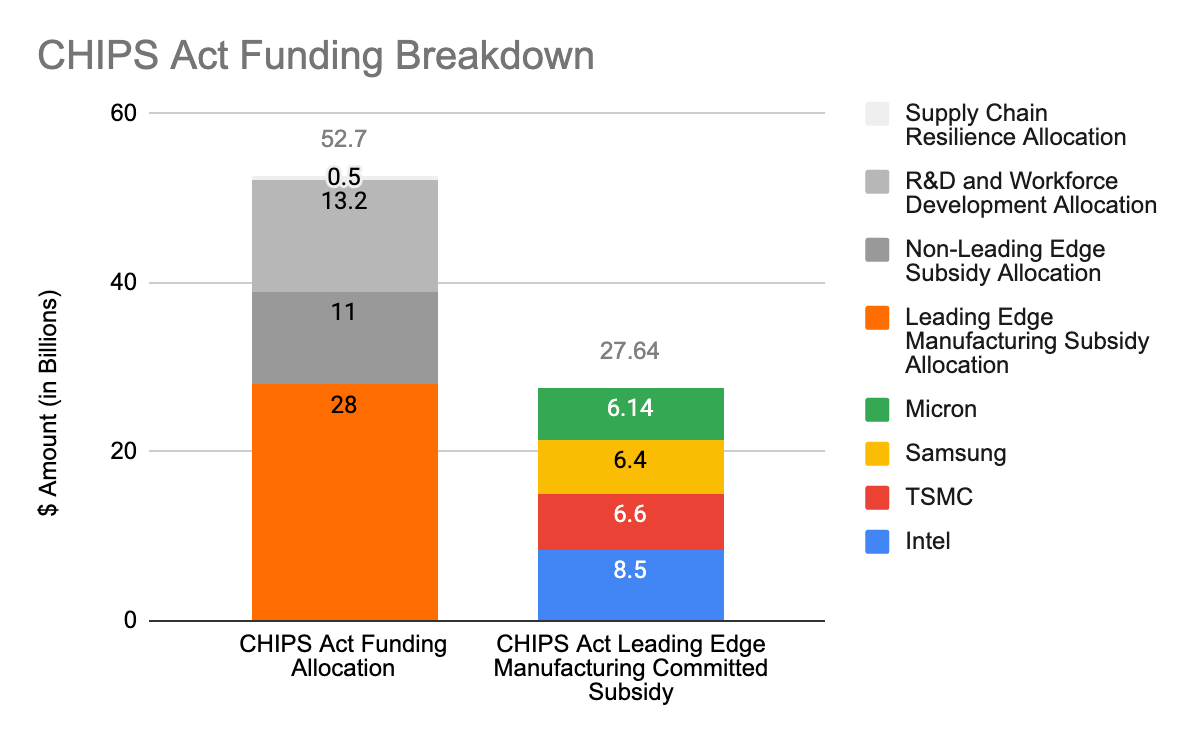

On April 25, 2024, the U.S. Department of Commerce announced the fourth, and most likely final, grant under the current U.S. CHIPS Act for leading-edge semiconductor manufacturing. With a Preliminary Memorandum of Terms (or PMT) valued at $6.14B, Micron Technologies joined the ranks of Intel Corporation, TSMC, and Samsung, each of which is slated to receive between $6.4 and $8.5B in grants to build semiconductor manufacturing capacity in the United States. Together, these four allotments total $27.64B, just shy of the $28B that Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo announced would be allocated to leading-edge manufacturing under the U.S. CHIPS Act. The Secretary of Commerce has stated ambitions to increase America’s global share in leading-edge logic manufacturing to 20% by the end of the decade, starting from the nation’s current position at 0%. But will the $27.64B worth of subsidies be enough to achieve this lofty goal?

To track achievement toward the 20% goal, one needs both a numerator and a denominator. The denominator consists of global leading edge logic manufacturing while the numerator is limited to leading edge logic manufacturing in the United States. Over the next decade, both the numerator and the denominator will be subject to large-scale changes, making neither figure easy to predict. For nearly half a century, the pace of Moore’s Law’s has placed the term “leading-edge” in constant flux, making it difficult to determine which process technology will be considered leading-edge in five years’ time. More recently, American chip manufacturing must keep pace with foreign development, as numerous countries are also racing to onshore leading-edge manufacturing. These two moving targets make it difficult to measure progress toward Secretary Raimondo’s stated goal and warrant a closer examination of the potential challenges faced.

Challenge #1: Defining Leading Edge and Success Metrics

The dynamic nature of Moore’s Law, which predicts the number of transistors on a chip will roughly double every two years (while holding costs constant), leads to a steady stream of innovation and rapid development of new process technologies. Consider TSMC’s progression over the past decade. In 2014, it was the first company to produce 20 nm technology at high volume production. Now, in 2024, the company is mass producing logic technology within the 3 nm scale. Intel, by comparison, is currently mass producing its Intel 4. (In 2021, Intel renamed its Intel 7nm processors to Intel 4.)

Today, the definition of advanced technologies and leading edge remains murky at best. As recently as 2023, TSMC’s Annual Report identified anything smaller than 16 nm as leading edge. A recent Trend Force report used 16 nm as the dividing line between “advanced nodes” and mature nodes. Trend Force predicts that U.S. manufacturing of advanced nodes will grow from 12.2% to 17% between 2023 and 2027, while Secretary Raimondo declared “leading-edge” manufacturing will grow from 0% to 20% by 2030. This lack of clarity dates back to the 2020 Semiconductor Industry Association (“SIA”) study which served as the impetus for the U.S. CHIPS Act. The 2020 SIA report concluded that U.S. chip production dropped from 37% to 10% between 1999 and 2019 based upon total U.S. chip manufacturing data. To stoke U.S. fears of lost manufacturing leadership, it pointed to the fast-paced growth of new chip factories in China, though none of these would be considered leading-edge under any definition.

A new 2024 report by the SIA and the Boston Consulting Group on semiconductor supply chain resilience further muddies the waters by shifting the metrics surrounding the advanced technologies discourse. It defines semiconductors within the 10 nm scope as “advanced logic” and forecasts that the United States’ position in advanced logic will increase from 0% in 2022 to 28% by 2032. It also predicts that the definition of “leading-edge” will encompass technologies newer than 3 nm by 2030 but fails to provide any projection of the United States’ position within the sub3 nm space. This begs the question: Should Raimondo’s ambition to reach 20% in leading edge be evaluated under the scope of what is now considered as “advanced logic”, or should the standard be held to a more rigorous definition of “leading edge”? As seen within the report, U.S. manufacturing will reach the 20% goal by a comfortable margin if “advanced logic” is used as the basis for evaluation. Yet, the 20% goal may be harder to achieve if one were to hold the stricter notion of “leading edge”.

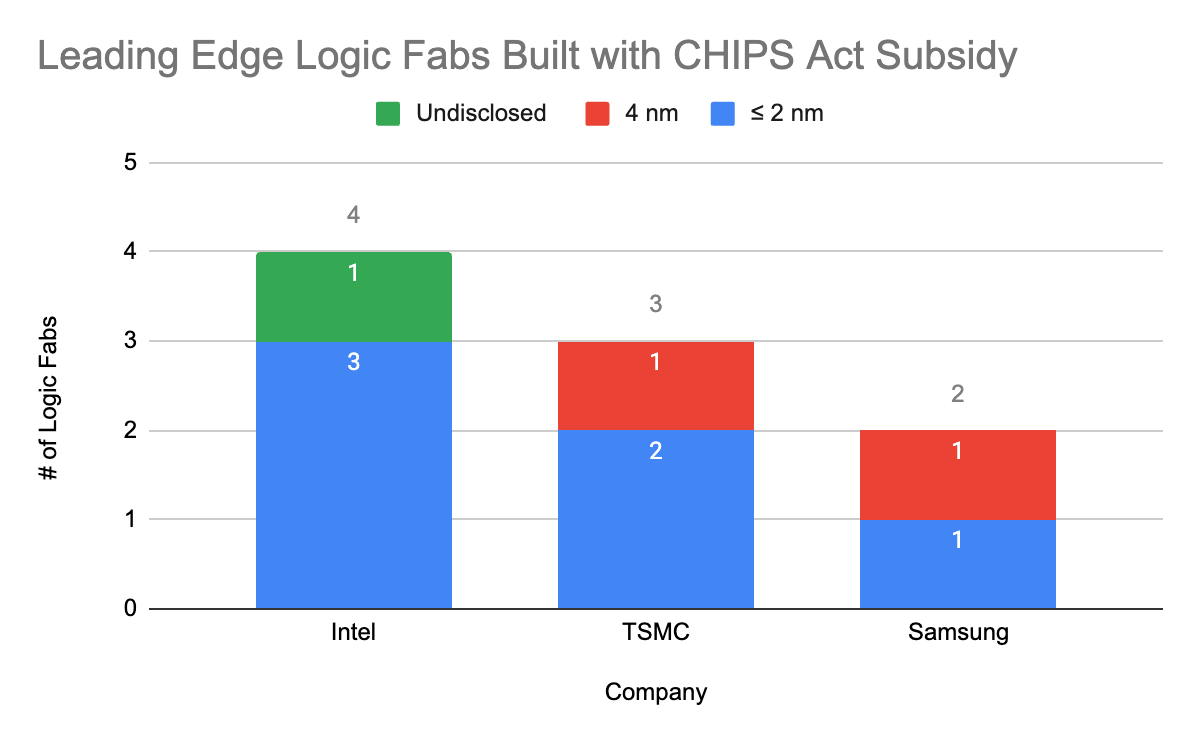

The most current Notice of Funding Opportunity under the U.S. CHIPS Act defines leading-edge logic as 5 nm and below. Many of the CHIPS Act logic incentives are for projects at the 4 nm and 3 nm level, which presumably meet today’s definition of leading-edge. Intel has announced plans to build one 20A and one 18A factory in Arizona, two leading edge factories in Ohio, bring the latest High NA EUV lithography to its Oregon research and development factory, and expand its advanced packaging in New Mexico. TSMC announced it will use its incentives for 4 nm FinFet, 3 nm, and 2 nm but fails to identify how much capacity will be allocated to each. Similarly, Samsung revealed its plans to build 4nm and 2 nm, as well as advanced packaging, with its CHIPS Act funding. Like TSMC, Samsung has not shared the volume production it expects at each node. However, by the time TSMC’s and Samsung’s 4 nm projects are complete, it’s unlikely they will be considered leading-edge by industry standards. TSMC is already producing 3 nm chips in volume and is expected to reach high volume manufacturing of 2 nm technologies in the next year. Both Intel and TSMC are predicting high volume manufacturing of sub-2nm by the end of the decade. In addition, the Taiwanese government has ambitions to break through to 1 nm by the end of the decade, which may lead to an even narrower criterion for “leading-edge.”

In this way, the United States’ success will be contingent on the pace of developments within the industry. So far, the CHIPS Act allocations for leading-edge manufacturing are slated to contribute to two fabrication facilities producing at 4 nm, and six at 2 nm or lower. If “leading-edge” were to narrow down to 3 nm technologies by 2030 as predicted, roughly a fourth of the fabrication facilities built for leading-edge manufacturing will not contribute to the United States’ overall leading-edge capacity.

If the notion of “leading-edge” shrinks further, even fewer fabrication facilities will be counted towards the United States’ leading-edge capacity. For instance, if the Taiwanese government proves to be successful with its 1 nm breakthrough, it would cast further doubt on the validity of even a 2 nm definition for “leading-edge”. Under such circumstances, the Taiwanese government will not only be chasing a moving target, but will shift the goalpost for the rest of the industry in the process, greatly complicating American efforts to reach the 20% mark. Thus, it becomes essential for the American leadership to keep track of foreign developments within the manufacturing space while developing its own.

Challenge # 2: Growth in the United States Must Outpace Foreign Development

Any measure of the success of the CHIPS Act must consider not only the output of leading edge fabrication facilities built in the United States, but also the growth of new fabs outside the United States. Specifically, to boost its global share of leading edge capacity by 20%, the U.S. must not only match the pace of its foreign competition, it must outpace it.

This means the U.S. must contend with Asia, where government subsidies and accommodating regulatory environments have boosted fabrication innovation for decades. Though Asian manufacturing companies will contribute to the increase of American chipmaking capabilities, it appears most chipmaking capacities will remain in Asia through at least 2030. For instance, while TSMC’s first two fabrication facilities in Arizona can produce a combined output of 50,000 wafers a month, TSMC currently operates 4 fabrication facilities in Taiwan that can each produce up to 100,000 wafers a month. Moreover, Taiwanese companies have announced plans to set up 7 additional fabrication facilities on the island, 2 of which include TSMC’s 2 nm facilities. In South Korea, the president has unveiled plans to build 16 new fabrication facilities through 2047 with a total investment of $471 billion, establishing a fabrication mega-cluster in the process. The mega-cluster will include contributions by Samsung, suggesting expansion of Korea’s leading-edge capacity. Even Japan, which has not been home to logic fabrication in recent years, has taken steps to establish its leading-edge capabilities. The Japanese government is currently working with the startup Rapidus to initiate production for 2 nm chips, with plans of a 2 nm and 1 nm fabrication facility under way. While the U.S. has taken a decisive step to initiate chipmaking, governments in Asia are also organizing efforts to establish or maintain their lead.

Asia is not the only region growing its capacity for leading edge chip manufacturing. The growth of semiconductor manufacturing within the E.U. may further complicate American efforts to increase its leading-edge shares by 20%. The European Union recently approved of the E.U. Chips Act, a $47B package that aims to bring the E.U.’s global semiconductor shares to 20% by 2030. Already, both Intel and TSMC have committed to expanding semiconductor manufacturing in Europe. In Magdeburg, Germany, Intel seeks to build a fabrication facility that uses post-18A process technologies, producing semiconductors within the order of 1.5 nm. TSMC, on the other hand, plans to build a fabrication facility in Dresden, producing 12/16 nm technologies. Though the Dresden facility may not be considered leading-edge, TSMC’s involvement could lead to more leading-edge investments within European borders in the near future.

In addition to monetary funding under the CHIPS Act, the U.S. also faces non-monetary obstacles that may hamper its success. TSMC’s construction difficulties in Arizona have been well-documented and contrasted with the company’s brief and successful construction process in Kumamoto, Japan. Like TSMC, Intel’s U.S. construction in Ohio has also faced setbacks and delays. According to the Center for Security and Emerging Technology, many countries in Asia provide infrastructure support, easing regulations in order to accelerate the logistical and utilities-based processes. For instance, during Micron’s expansion within Taiwanese borders, the Taiwanese investment authority assisted the company with land acquisition and lessened the administrative burden the company had to undergo for its construction. The longer periods required to obtain regulatory approvals and complete construction in the U.S. provide other nations with significant lead time to outpace U.S. growth.

Furthermore, the monetary benefits of CHIPS Act rewards will take time to materialize. Despite headlines claiming CHIPS Act grants have been awarded, no actual awards have been issued. Instead, Intel, TSMC, Samsung and Micron have received Preliminary Memorandum of Terms, which are not binding obligations. They are the beginning of a lengthy due diligence process. Each recipient must negotiate a long-form term sheet and, based upon the amount of funding per project, may need to obtain congressional approval. As part of due diligence, funding recipients may also be required to complete environmental assessments and obtain government permits. Government permits for semiconductor factories can take 12- 18 months to obtain. Environmental assessments can take longer. For example, the average completion and review period for an environmental impact statement under the National Environmental Policy Act is 4.5 years. Despite the recent announcements of preliminary terms, the path to actual term sheets and funding will take time to complete.

Even if the due diligence and term sheets are expeditiously completed, the recipients still face years of construction. The Department of Commerce estimates a leading-edge fab takes 3-5 years to construct after the approval and design phase is complete. Moreover, two of the four chip manufacturers have already announced delays in construction projects covered by CHIPS Act incentives. Accounting for 2-3 years to obtain permits and complete due diligence, 3-5 years for new construction, and an additional year of delay, it may be 6-9 years before any new fabs begin production. To achieve the CHIPS Act goal of 20% by 2030, the United States must do more than provide funding– it must ensure the due diligence and permitting processes are streamlined to remain competitive with Europe and Asia.

The Future of Leading-Edge in the United States

Between the constant changes in the meaning of “leading-edge” under Moore’s Law and the growing presence of foreign competition within the semiconductor industry, the recent grant announcements of nearly $28B for leading-edge manufacturing are only the start of the journey. The real test for the U.S. CHIPS Act will occur over the next few years, when the CHIPS Office must do more than monitor semiconductor progress within the U.S. It must also facilitate timely completion of the CHIPS Act projects and measure their competitiveness as compared to overseas expansions. The Department of Commerce must continually evaluate whether its goals still align with developments in the global semiconductor industry.

As such, whether the United States proves successful largely depends on why achieving the 20% target matters. Is the goal to establish a steady supply of advanced logic manufacturing to protect against foreign supply-side shocks, or is it to take and maintain technological leadership against the advancements of East Asia? If the former case, then abiding to the notion of “advanced logic” will suffice; the degree of such an achievement will be smaller compared to what was initially promised under “leading-edge”, but it remains a measured and sensible goal for the U.S. to achieve. If the latter case holds true, achieving the 20% benchmark would place the United States in a much stronger position within the global supply chain. To do so, however, will undoubtedly require much greater funding efforts towards leading-edge than the $28B that has been allocated.

National governments are increasingly investing efforts to establish a stronger productive capacity for semiconductors, and many will continue to do so in the succeeding decades. If the United States aims to keep pace with the rest of the industry, then it must maintain a steady stream of support towards leading-edge technologies. It will be an expensive initiative, but some leading figures such as Secretary Raimondo are already suggesting a secondary CHIPS Act to expand upon its initial efforts; In the global race, another subsidy package will provide the nation with a much needed push towards the 20% finish line. Hence, despite all the murkiness surrounding the United States’s fate within the semiconductor industry, one fact remains certain: the completion of the CHIPS Act should not be seen as the conclusion, but as the prologue to America’s chipmaking future.

Also Read:

Micron Mandarin Memory Machinations- CHIPS Act semiconductor equipment hypocrisy

The CHIPS and Science Act, Cybersecurity, and Semiconductor Manufacturing

Share this post via:

Comments

2 Replies to “The Case for U.S. CHIPS Act 2”

You must register or log in to view/post comments.