Near the end of Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire” the Blanche DuBois character, who has suffered a mental breakdown following an implied rape, tells the doctor and matron who have come to take her to the hospital: “Whoever you are – I have always depended on the kindness of strangers.” Sadly, this is the same mentality of municipalities turning to Waze to resolve traffic troubles.

More than 3,000 municipalities around the world – according to Waze – have turned to the popular navigation app to better understand their own traffic woes and resolve challenges. The irony here, of course, is that Waze often CREATES traffic problems by routing vehicles through neighborhoods abutting major highways – or even navigating users into dangerous areas such as favelas in Brazil, occupied territories in Israel, or forest fire zones in California.

Waze’s traffic insights are derived from crowd-sourced “probe” data from users of the app. The location data from users’ mobile phones traces the pace and direction of travel and users can report road hazards or the location of law enforcement vehicles for the benefit of other drivers.

The result – when calibrated to convert real-time data into predictive traffic models – is a compelling navigation tool that has put pressure on car makers that offer built-in navigation systems that often use outdated maps. Waze claims 140M users worldwide and that kind of ubiquity is hard to ignore.

It’s also hard to ignore the fact that Waze has yet to define a profit-generating business model. The sheer desperation of this effort is reflected in the increasingly distracting array of display advertising that shows up in the app while in use. Oddly, you can’t enter a destination into the app while driving, but the app can try to distract you with impossible to read advertisements while it is navigating.

The source of Waze’s strength, though, is also its greatest weakness. Waze has no reliable means to validate the user inputs regarding hazards and other observations – and on multiple occasions users have punked Waze into re-routing drivers away from particular neighborhoods or locations.

Waze has also been known to use its negative impact on local traffic patterns as a door opener with local municipalities. Waze creates the traffic problem – blamelessly! – and then begins collaborating with local traffic authorities to “hack” the app to overcome the routing snafu that is riling citizens.

In the end, Waze is still relying on the “kindness” of strangers and the company runs its Waze for Cities program almost like a protection racket – mesmerizing cities into relying on Waze to fix their traffic problems by using it as a communication conduit. In one such case, Sandy Springs, Georgia, officials joined forces with Waze to communicate confusing traffic patterns to drivers through the app. This alone on its face isn’t such a horrible idea, but in the context of failing to communicate the same information via 511 services or embedded navigation systems from Telenav, NNG, TomTom, and HERE or even via radio stations drives even more users to Waze.

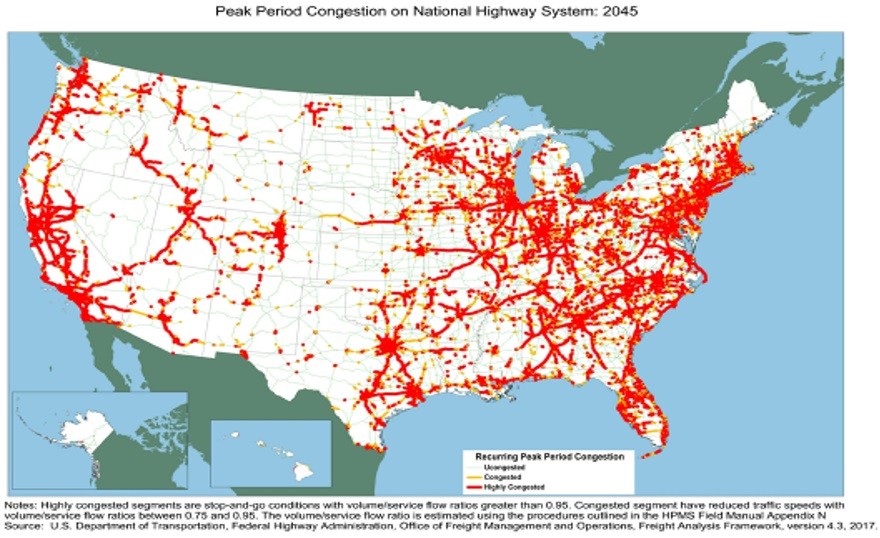

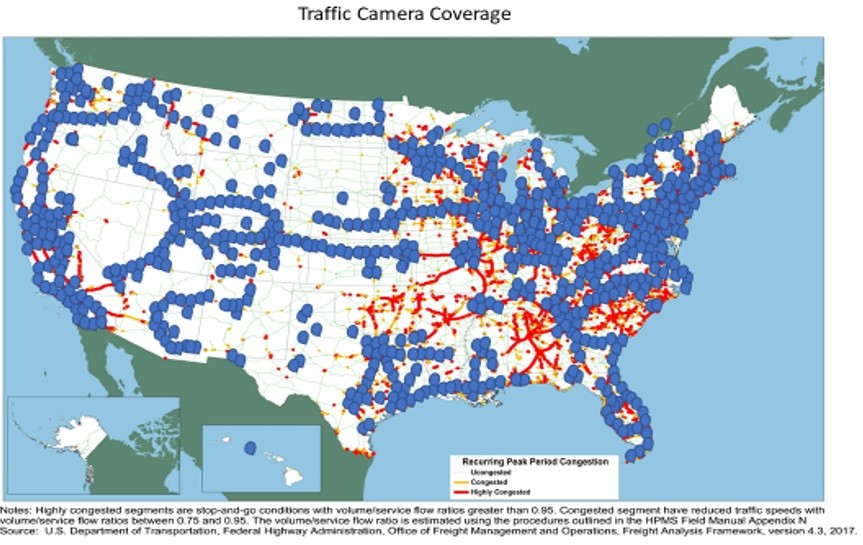

The strangest thing about cities that have turned to Waze as a partner and a communications tool is that most cities have their own traffic information resources. In fact, cities have access to traffic cameras – thousands of them – mostly trained on predictable traffic hotspots.

In the U.S., the leading provider of nationwide traffic camera information is TrafficLand. TrafficLand is responsible for nearly half of all server-side traffic camera installations and is able to deliver still images or streaming video on demand. The company also performs digital analytics on the images it gathers.

With a proper front-end interface, built-in vehicle navigation systems could tap into TrafficLand content to allow drivers to make better-informed navigation decisions. There’d be no need to “trust” Waze, in this instance. Still images or video would confirm the reality of traffic conditions on the road ahead.

Better yet, what about auto makers as a source of front-facing camera data. Mercedes-Benz and the Netherlands’ Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management have announced a two-year project whereby Mercedes-Benz will share anonymized sensor data from its vehicles with the agency for the identification of road safety hotspots and maintenance issues. The key difference here is the reliance on vehicle sensors – which include cameras – that generate verifiable and reliable inputs.

Between fixed cameras (TrafficLand) and vehicle-mounted cameras, local municipalities ought to be able to identify and resolve their traffic issues – without the assistance of Waze and its user-generated inputs. Cities can then share their data resources with any and all traffic information and navigation providers – not just Waze.

In fact, every city should have a data exchange program in place in which auto makers could participate. That could be a job for Telenav or NNG or HERE or TomTom. But please, not Waze. We shouldn’t rely entirely on strangers for our traffic insights when we can observe reality directly in real time.

Also read:

Auto Safety – A Dickensian Tale

Share this post via:

The Intel Common Platform Foundry Alliance