There was a day, not too long ago, when a software developer could be intimate with a processor through understanding its register set. Before coding, developers would reach for a manual, digging through pages and pages of 1s and 0s with defined functions to find how to gain control over the processor and its capability. One bit set or cleared in the right place could be the key to making an application work.

Leaps in processor performance and increases in memory size made hand-crafted code less important, and high level languages took hold as a way to increase coding productivity. Developers graduated from bit-twiddling I/O to more sophisticated functions like disk storage and networking stacks and GUIs, and the real-time operating system emerged with code to set up and manage peripherals.

Peripherals started to coalesce on functional standards like USB and SATA, reducing the variety of interfaces programmers had to deal with. Standardized interfaces like PCI and PCI Express and RapidIO further abstracted the peripheral, seamlessly extending the processor beyond the boundaries of its local bus while allowing complex functions to be added.

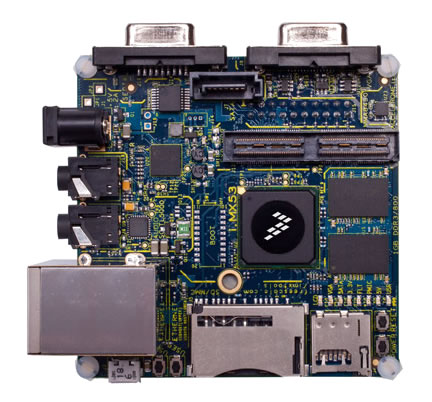

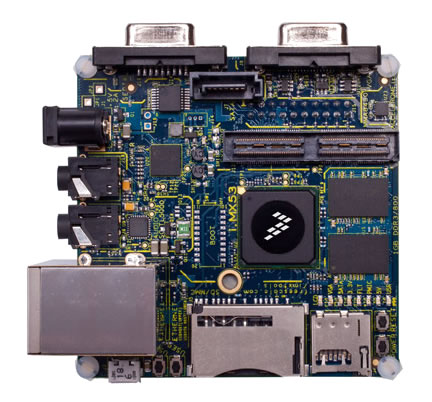

Then, a funny thing happened: the system-on-chip (SoC) movement took all the exposed functions developers were used to, glued them together and buried them deep inside a complex beast of a chip. While this drove an incredible revolution in size and performance, it has made a nightmare for developers to really optimize their execution environment, accounting for all the capability an SoC presents. In many cases, the IP blocks inside an SoC are black-boxes to developers who hope beyond hope to get a driver that works for an operating system.

While it’s still possible to figure out programming an SoC, excavating into what in some cases is over 2000 pages of documentation for the part not to mention docs for the operating system, it all takes precious time. Developers have to be experts on their application, and smaller departments have little hope of time left over to develop a deep understanding of the SoC inside. This used to be a gap the board vendors would fill, in taking an operating system and creating a board support package with the drivers packaged together. As the value-add of a board vendor working with an SoC diminishes, fewer board vendors are interested, and this task is swinging back to the semiconductor and operating system firms.

In practice today, that’s the only hope for applications running on SoCs: a tight relationship between the semiconductor company and the operating system company that produces abstracted and optimized support for the myriad of functions inside. Otherwise, developers have to be experts on processor cores, caching and MMU operation, graphics, networking, storage, USB, DSP, audio, compression, encryption, and more functions. That’s a 7 or 8 dollar figure effort for a large project, and it’s impossible for projects with typically embedded volumes of a couple thousand.

This new model is taking shape in quite a few places, but perhaps nowhere as broadly as Mentor Graphics. This week, Mentor announced up-to-date support for 42 embedded SoC boards on their RTOS and Linux environments (proving the answer to the universe and everything embedded is actually 42). The philosophy is Mentor’s embedded software teams live with the SoC vendors at the front end, so you don’t have to in order to get a solid starting point for software. Again, they’re not unique in this type of effort, but the range of relationships and architecture support Mentor is putting together is impressive.

You can still read the SoC manual, if you have time. Seriously, what are your views? Is this type of support for SoCs valuable, or can a development team with enough caffeine still do without it? Does open source (read: free) provide enough, or is value-added support worth a reasonable expenditure? Do you know of an example where this type of integrated, value-added support boosted productivity and got a project done faster than thought possible? Or saved a project that got in trouble?

(Disclaimer: Been away a while, long story, happy to be writing again)

Comments

There are no comments yet.

You must register or log in to view/post comments.