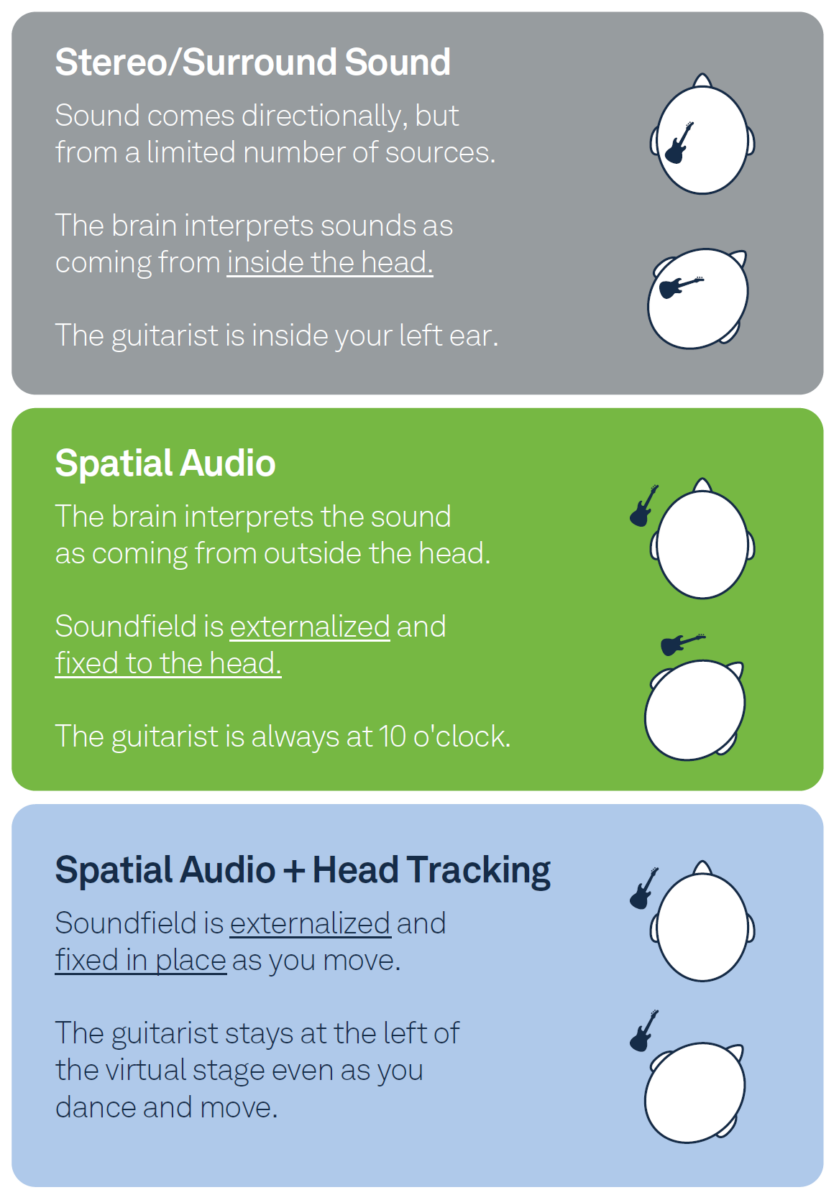

Spatial audio technologies deliver more realistic sound by manipulating how the listener perceives sounds virtually sourced from different directions and distances in a 3D space. Where traditional surround sound technology uses various sound channels through many speakers positioned around a listener, spatial audio can deliver immersive experiences from fewer speakers in smaller packages, such as in a pair of earbuds or a compact soundbar. Kaushik Sethunath, Audio Test Engineer at Ceva, shared some thoughts leading into his series of blog posts explaining spatial audio concepts and parameters that help define innovative designs.

Better sound is intensely subjective for each listener

Audio has been the subject of intense scrutiny from expert reviewers since the initial development of high-fidelity analog recordings on 33rpm vinyl in 1948. Studio engineers became proficient at mixing multiple recorded tracks into stereo formats. At the peak of the vinyl format, 1970s bands like Steely Dan and Pink Floyd produced albums renowned for their complex yet crisp sound, becoming benchmarks for consumer stereo systems.

What constituted “stereo” sound was relatively simple, with left and right speakers standard and optional center and subwoofer channels on higher-end gear. If one spent more money on equipment – sensitive, mechanically smooth turntables, amplifiers with lower distortion and noise and higher dynamic range, and larger, more powerful speakers with improved response – the sound was, at least in theory, perceptibly better.

However, with so many variables in analog audio, including differences in the frequency sensitivity of each listener’s ears, better sound was a subjective measure. Vinyl records would degrade with handling and excessive play, altering even great experiences. Then, audio went digital, first on physical CDs, then in file formats such as MP3. Digital recordings don’t degrade over time, and new delivery mechanisms appeared.

Perhaps more importantly, digital audio technology ushered in significant engineering changes. Users moved from large, fixed stereo equipment and the 12” vinyl format to smaller, less expensive portable gear playing CDs or files. Some audio engineers responded by recording content for listening through lower-quality headphones in noisy ambient settings, using higher sound levels with less dynamic range, leaving the sound good enough for most listeners.

Use cases drive a need for an audio parameter framework

In the last few years, the pendulum has swung back: consumers can now buy digital audio technology rivaling high-end surround sound systems in affordable soundbars and earbuds, with pervasive streaming technology delivering more sophisticated audio formats like Dolby Atmos and DTS:X. The low-quality approaches to content are leaving listeners wanting more, and they are willing to spend incrementally more to get better quality they can hear.

“Trying to preserve the integrity of the original artist’s vision is really important,” says Sethunath. “We think the best way to experience sound is with different settings for different content. A podcast heard while commuting is a very different use case from a movie in the comfort of a home theater, and gamers have other needs, so there is no one-size-fits-all. Accordingly, based on the content, the parameters of the spatial audio processing need to be tuned, to create the appropriate spatial experience.”

Sethunath sees a more complex landscape where the industry lacks a framework to compare and quantify audio performance in different use cases. He proposes eight technical parameters in two broad categories to guide both spatial audio device design and content curation:

- Spatialization

- Degree of Externalization

- Room Character and Presets

- Maximum Number of Channels Rendered

- Mono and Stereo Rendering

- Artifacts

- Head Tracking

- Latency

- Degrees of Freedom

- Artifacts

There are tradeoffs and design decisions with host-based rendering (using the power of phones and tablets to do the heavy lifting of spatial audio processing) and embedded rendering on the headset (lowest latency, but without direct multi-channel support due to Bluetooth bandwidth limitations). Ceva provides optimized solutions for both architectures, including head tracking technology to enhance realism in affordable devices.

“I think creating a smoother onboarding process to spatial audio, walking people through what it can do and content that highlights the experience, will be compelling,” says Sethunath. He’s created a new series of three blog posts on spatial audio concepts, explaining the parameters in more detail and describing how designers can evaluate implementations. Links to the posts:

Evaluating Spatial Audio – Part 1 – Criteria & Challenges

Evaluating Spatial Audio – Part 2 – Creating and Curating Content for Testing

Evaluating Spatial Audio – Part 3 – Creating a Repeatable System to Evaluate Spatial Audio

For readers interested in Ceva’s IP with solutions for head tracking, more info is also online:

Ceva-RealSpace: Spatial Audio & Head Tracking Solution

Share this post via:

Comments

There are no comments yet.

You must register or log in to view/post comments.