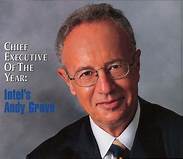

I met Andy Grove on a sunny day in New York City in 1987. He was dashing to press interviews for his just-off-the-presses management book, “One on One with Andy Grove.” I was a freshly badged member of the press working for IEEE Spectrum, a year or so out of college, still toting my college backpack. Little did I know that that would be the first of dozens of conversations I would have with Grove over more than two decades.

I met Andy Grove on a sunny day in New York City in 1987. He was dashing to press interviews for his just-off-the-presses management book, “One on One with Andy Grove.” I was a freshly badged member of the press working for IEEE Spectrum, a year or so out of college, still toting my college backpack. Little did I know that that would be the first of dozens of conversations I would have with Grove over more than two decades.

Grove was a self-made American original. He fled Hungary in 1956 when the Russians invaded, heading to the US with choppy English and bright ambitions. He reinvented himself along the way: He dropped the Hungarian “Andras Grof” for the more comfortable, “Andy Grove.” He spent a summer as a busboy at a resort in New Hampshire—and graduated at the top of his engineering class at City College in New York in three years. Impatient with the plodding pace of east coast companies, he gambled on California.

He was frequently an exasperating boss. “Occasionally we . . . suggest [to Grove] there may be an alternative to grabbing someone and slamming them over the head with a sledgehammer,” grumbled Craig Barrett (who followed Grove as CEO) in a 1996 interview. Others would call that an understatement.

In the years since my first Grove encounter, I’ve chronicled how he battled critics who called Intel’s chips “flawed,” pumped up Intel’s market success by hiring the “Blue Men,” and was humbled by being named Time’s Man of the Year. After Grove retired from Intel, I’d visit him periodically for a brisk walk up and down the hills near his Los Altos home.

When I started and became CEO of my own company, EdSurge, I discovered I appreciated many of Grove’s points afresh–even if I didn’t follow them all. I’m no fan of his “constructive confrontation” approach. Even though Grove aimed to “attack the problem not the individual,” too frequently the “confrontation” could overwhelm the, ah, “constructive” parts. More recently, managers practice instead “radical candor.” I suspect that Grove, who was a perennial student of the latest thinking in management practices, might have appreciated both the feedback–and a fresh approach.

Here are a few of the powerful lessons I learned from Andy Grove:

It’s okay to be scared. When Grove joined Intel as its first official employee in 1968, he said he was “scared to death.” He was supposed to be director of engineering but because the team was so small, Grove became director of operations. First task: Get a post office box and sign up for catalogues of equipment the startup couldn’t afford. “I literally had nightmares.”

Relish reality. After World War II, Grove and his family stayed in Hungary, only to see the corrosive effects of passive politeness. When he finally fled in late 1956, he headed to Vienna via train and had an epiphany: “After all the years of pretending to believe things that I didn’t, of acting the part of someone I wasn’t, maybe I would never have to pretend again.”

Discipline, discipline, discipline. (Did I mention discipline?) Obsessed with details, Grove oversaw manufacturing, which became key to Intel’s success. The best chip design in the world would be worthless without the manufacturing discipline to churn out millions of copies. And any time a problem occurred, Grove drove his people to attack it like a virus until it was fixed. He demanded a lot of himself–and his team. Grove was infamous for creating a “late sheet” kept by security that anyone who showed up for work after 8:00 a.m. had to sign. Employees were terrified of the late sheet. Grove eventually admitted that he never looked at it—its mere existence prodded people to show up on time.

When the going gets tough, suck it up. In November 1976, Grove wrote in his personal journal: “[D]issatisfied w/overall co. performance (hence: me!) … frequently depressed; thoughts of bailing out.” He didn’t.

Teach with humility. For years, Grove co-taught a class at Stanford University’s business school on strategy with long-time collaborator, Robert Burgelman. He tested ideas with students. He respected students, coaxing friends and well-known entrepreneurs, including Steve Jobs, to support him by putting in guest appearances. It was neither boastful nor for show: He also demanded students rigorously critique Intel’s choices, including pivotal ones about what microprocessor architecture to pursue in the mid 1990s. (Engineers were in love with an elegant architecture called RISC; Grove eventually stuck with a more evolutionary approach, CSIC.)

Learn with passion. Over the years, I have interviewed countless industry leaders and other mucky-mucks. Grove was unique in that he seized every conversation as an opportunity to learn not just to lecture. I remember swinging by his Intel cubical one day after recent interviews with other executives pioneering work in handheld devices and mentioning some of the emerging technologies that seemed promising. “Who was that? Why was it interesting?” he demanded, grabbing a notepad and scribbling furiously. It wasn’t just about competitors: He was boundlessly interested in learning about journalism, politics, social practices, recent books — you name it.

Did you screw up? Admit it. This one was hard for him. When Intel confronted a wave of unhappy customers because of a subtle flaw in the arithmetic functions of Intel’s Pentium processor, Grove refused to believe it mattered. He dragged his feet on apologizing to customers until the howling both inside and outside of the company was deafening. Finally, he agreed to take the chips back. “I was thick-headed. I don’t know how to say that differently,” Grove later said.

Science the shit out of your problems. Grove would have loved Matt Damon’s line in the “The Martian,” as he realizes he’s stuck on Mars without enough food or water: “I’m going to have to science the shit out of this.” When Grove was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1995, he dove into research about treatment alternatives, plotting out data in detailed analyses. He chose the path the data suggested—a successful pick. A few years later, he realized he had Parkinson’s disease. Once again, he “science’d” up, immersing himself in the details of the condition and the research, experimenting with treatments and agitating for more and faster research on the neurology of Parkinson’s.

Be real. “Beware of hypocrisy in the boss! The worst situation is when the boss says one thing and does another.” That was Grove’s advice in his book, One on One. And he tried to live it. Intel was among the first companies to eschew the “corner office.” Grove had a cubical, like just about all other Intel managers. He kept it real at home, too. Even when Grove and his wife became wealthy beyond their dreams, they continued to live in the house where they raised their daughters. Instead of doing movie cameos, the Groves more typically could be spotted around town waiting in a line at the theater.

Love fiercely. For Grove and his family, Intel was like a third, sometimes unruly, child. He continued to actively follow Intel’s work years into his retirement. Even so, there was competition for his heart: his wife, Eva. When Grove wrote his personal memoir, Swimming Across, he offers scant details about his personal life once he arrived in America. But family and friends received a bonus section, though: Grove added a “long-lost” chapter about how he met and wooed Eva, whom he married at age 21. She remained the love of his life until his final breath.

Betsy Corcoran is a long-time journalist and entrepreneur, working at the intersection of learning and technology. Follow her on LinkedIn here.

Also Read:

CEO Interview: Deepak Shankar of Mirabilis Design

CEO Interview: Prakash Murthy of Atonarp

CEO Interview: Toshio Nakama of S2C EDA

Share this post via:

Comments

One Reply to “Ten Lessons Learned from Andy Grove”

You must register or log in to view/post comments.