In one of those odd coincidences, I was having dinner with a friend last week and somehow the Carrington Event came up. Then I read a a piece in EETimesabout whether electrical storms could cause problems in the near future. Even that piece didn’t mention the Carrington Event so I guess George Leopold, the author, hasn’t heard of it.

It constantly surprises me that people in electronics have not heard of the Carrington Event, the solar storm of 1859. In fact my dinner companion (also in EDA) was surprised that I’d heard of it. But it is a “be afraid, be very afraid” type of event that electronics reliability engineers should all know about as a worst case they need to be immune to.

Solar flares go in an 11-year cycle, aka the sunspot cycle. The peak of the current cycle is 2013 or 2014. This cycle is unusual for its low number of sunspots and there are predictions that we could be in for an extended period of low activity like the Maunder minimum from 1645-1715 (the little ice age when the Thames froze every winter) or the Dalton minimum from 1790-1830 (where the world was also a couple of degrees colder than normal). Global warming may be just what we need, it is cooling that causes famines.

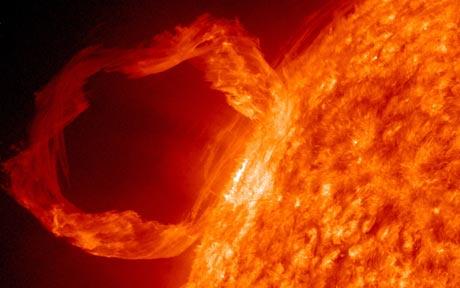

But for electronics, the important thing is the effect of coronal mass ejection which seems to cause solar flares (although the connection isn’t completely understood). Obviously the most vulnerable objects are satellites since they lack protection from the earth’s magnetic field. There was actually a major event in March but the earth was not aligned at a vulnerable angle and so nothing much happened and the satellites seemed to survive OK.

But let’s go back to the Carrington Event. It took place from August 28th to September 2nd 1857. It was in the middle of a below average solar cycle (like the current one). There were numerous solar flares. One on September 1st, instead of taking the usual 4 days to reach earth, got here in just 17 hours, since a previous one had cleared out all the plasma solar wind.

On September 1st-2nd the largest solar geomagnetic storm ever recorded occurred. We didn’t have electronics in that era to be affected but we did have telegraph by then. They failed all over Europe and North America, in many cases shocking the operators. There was so much power that some telegraph systems continued to function even after they had been turned off.

Aurora Borealis (Northern Lights) was visible as far south as the Caribbean. It was so bright in places that people thought dawn had occurred and got up to go to work. Apparently it was bright enough to read a newspaper.

Of course telegraph systems stretch for hundreds or thousands of miles so have lots of wire to intercept the fields. But the voltages involved seemed to be huge. It doesn’t seem that different from the magnetic pulse of a nuclear bomb. And these days, our power grids are huge, and connected to everything except our portable devices.

Imagine the chaos if the power grid shuts down, if datacenters go down, if chips in every car’s engine-control-unit fries or and all our cell-phones stop working. And even if your cell-phone survives and there is no power, you don’t have that long before its battery is out. It makes you realize just how dependent we are on electronics continuing to work.

In 1859 telegraph systems were down for a couple of days and people got to watch some interesting stuff in the sky. But from a NASA event last year in Washington looking at what would happen if another Carrington Event occured:In 2011 the situation would be more serious. An avalanche of blackouts carried across continents by long-distance power lines could last for weeks to months as engineers struggle to repair damaged transformers. Planes and ships couldn’t trust GPS units for navigation. Banking and financial networks might go offline, disrupting commerce in a way unique to the Information Age. According to a 2008 report from the National Academy of Sciences, a century-class solar storm could have the economic impact of 20 hurricane Katrinas.

Actually, to me, it sounds a lot worse than that. More like Katrina hitting everywhere, not just New Orleans. That’s a lot more than 20. To see how bad a smaller event can be:In March of 1989, a severe solar storm induced powerful electric currents in grid wiring that fried a main power transformer in the HydroQuebec system, causing a cascading grid failure that knocked out power to 6 million customers for nine hours while also damaging similar transformers in New Jersey and the United Kingdom.

Wikipedia on the Carrington Event is here. The discussion at NASA here.

Share this post via:

CEO Interview with Jerome Paye of TAU Systems