The cybersecurity of automobiles has become an increasingly critical issue in the context of autonomous vehicle development. While creators of autonomous vehicles may have rigorous safety and testing practices, these efforts may be for naught if the system are compromised by ethical or unethical hackers.

The cybersecurity of automobiles has become an increasingly critical issue in the context of autonomous vehicle development. While creators of autonomous vehicles may have rigorous safety and testing practices, these efforts may be for naught if the system are compromised by ethical or unethical hackers.

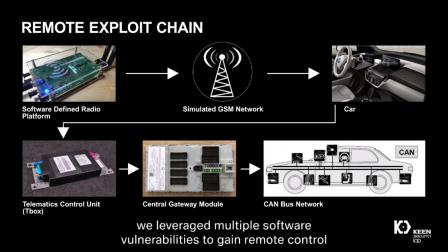

Establishing cybersecurity in a motor vehicle is a daunting proposition. Cars are exposed in unprotected areas such as parking garages and public roadways much of the time they are in operation. Cars are also increasingly connected to wireless cellular networks and nearly all cars built after 1996 are equipped with an OBD-II diagnostic port enabling physical access to vehicle systems.

The proliferation of smartphone connection solutions such as Android Auto, Apple Carplay, the CCC Consortium’s MirrorLink and the SmartDeviceLink Consortium’s SDLink have also opened a path to cybersecurity vulnerability. All of these attack surfaces were used by Tencent’s Keen Security Labs when the organization identified 14 vulnerabilities in BMW vehicles earlier this year.

It is hardly shocking the Keen found these vulnerabilities. What is shocking was BMW’s response.

As a member of the Auto-ISAC, based in the U.S., BMW was obliged to report vulnerabilities to the membership – encompassing upwards of 50 car companies and their suppliers – within 72 hours. Instead, BMW waited more than three months. (Note: It is possible that the part of BMW that was notified of the hack by Keen was not in touch with the BMW executives representing the company within the Auto-ISAC.)

]During that time, between notification by Keen and notification of the Auto-ISAC, BMW worked directly with Keen engineers and scientists to remedy the flaws found by Keen. In fact, there are multiple videos available online that describe the details of the hacks and the efforts to correct them – which included over-the-air software updates, a capability that reflected BMW’s design foresight.

BMW concluded the episode by giving Keen the first ever BMW Group Digitalization and IT Research Award and pledging to collaborate closely with Keen in the future. BMW was Keen’s second “victim.”

Two years ago Keen remotely hacked a Tesla Model S also resulting in fixes from Tesla delivered via over-the-air software updates. Keen performed a second Tesla hack a year later and ultimately Keen parent Tencent took a 5% stake in Tesla.

It’s not clear whether Tesla was a member of the Auto-ISAC at the time of the Keen hacks or whether it reported those hacks in a timely manner. But there are lessons to be learned from both hacks.

1. Even the most sophisticated cars designed by some of the cleverest engineers in the industry have been found to be vulnerable to physical and remote hacks;

2. In a world where cars are increasingly driven based on the guidance of software code, cybersecurity is suddenly an essential concern for which there is no immediate, obvious fix;

3. Over-the-air software update technology is a key part of the solution;

4. Car companies must report cybersecurity attacks and vulnerabilities in a timely manner – mainly because so many components and so much code is shared across multiple car makers;

5. Car makers are obliged to constantly test their own systems and foster bug bounty programs and ethical hacking of their own systems to identify vulnerabilities in a proactive manner.

Unlike cybersecurity hygiene for mobile devices, consumer electronics or desktop computers, car makers cannot wait until they are hacked to respond. Car makers must be in a constant state of cybersecurity vigilance and testing.

This need is reflected in a recent announcement from Karamba Security. The company has launched its ThreatHive. ThreatHive implements a worldwide set of hosted automotive ECUs in simulation of a “car-like” environment for automotive software system integrators.

According to Karamba: “These ECU software images are automatically monitored to expose automobile attack patterns, tools, and vulnerabilities in the ECU’s operating system, configuration and code.” In other words, Karamba is embedding pen testing of systems into the development cycle of automotive systems.

The Karamba solution reflects the fact that car makers cannot wait for an intrusion and the lengthy product development life cycle requires a means of hardening automotive systems prior to market launch. As for automotive cybersecurity generally or the security of a given BMW particularly, cars may never be fully or certifiably cybersecure.

Car makers need to come clean with their industry brethren via organizations such as the Auto-ISAC and, ultimately, must be honest with their customers. If BMW knows my BMW is insecure, they better let me know and let me know how they are going to or how they have fixed that vulnerability.

In the video describing the remediation a BMW engineer says that the corrective measures are “transparent” to the vehicle owner who “will not notice the difference.” Unfortunately, BMW appears to have misunderstood the meaning of “transparent.” When correcting cybersecurity flaws, car makers must disclose, not hide, their work to protect the consumer. That may be the biggest lesson of all from the Keen Security Lab hack of BMW and may be one of the more difficult obligations for the industry to accept.

Share this post via:

Flynn Was Right: How a 2003 Warning Foretold Today’s Architectural Pivot