The might have beens. The shoulda’s, coulda’s, woulda’s are what launches a thousand Harvard Business School Case Studies that are meant to prepare a generation of business leaders on how to make decisions that impact the future directions of companies. Right before the 2008 financial crises (September 5, 2008), Samsung made a run at Sandisk in order to reduce its NAND Flash royalty payments. A year later, Sandisk rejected Samsung’s final offer for what would be half the value of the company today. Samsung can look back and say that was a big fork in the road and hopefully for them it wasn’t a “stick a fork in it” moment.

The might have beens. The shoulda’s, coulda’s, woulda’s are what launches a thousand Harvard Business School Case Studies that are meant to prepare a generation of business leaders on how to make decisions that impact the future directions of companies. Right before the 2008 financial crises (September 5, 2008), Samsung made a run at Sandisk in order to reduce its NAND Flash royalty payments. A year later, Sandisk rejected Samsung’s final offer for what would be half the value of the company today. Samsung can look back and say that was a big fork in the road and hopefully for them it wasn’t a “stick a fork in it” moment.

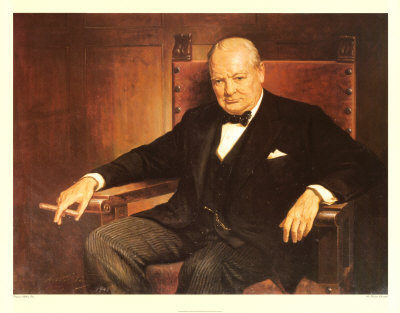

Winston Churchill, the man who saved Western Civilization was famous for saying “the farther backward you can look, the farther forward you are likely to see.” While he was forced to sit on the political sidelines in the 1930s during his “Wilderness Years”, he watch Britain and France run the same appeasement playbook while Germany re-arm with new tanks and planes. At age 65, he was called to lead Britain out of its darkest hour with only the technology of Radar and a 22-mile water barrier called the English Channel as his barrier to defeat. The beaches of Dunkirk were left littered with the bulk of Britain’s military equipment. As one of the fathers of the WWI tank and a through and through military technologist he could tie the nuts and bolts of capability with an overarching strategy. None was his equal. What’s this got to do with semiconductors?

There is only one semiconductor executive that has been there from the early, early days of the 1970s of Noyce, Moore and Grove. From the days of DRAM, the EPROM, the 8 bit microprocessor all the way to today’s multi-core 64 bit processors there is only one who was personally tutored by Andy Grove and who has the ability to look farther back in semiconductors in order to see what lies farther ahead. This person is Paul Otellini, who has built an Intel that in 2012 will likely end up being 3 times as profitable as in the bubble year of 2000, the peak of the disastrous Craig Barrett “Itanium Era.”

Competing in the semiconductor industry often times is a multi-front war. If you can’t visualize your enemies or the enemies of your enemies, then you will die somewhere in the next turn of Moore’s Law. Intel has recognized this for a long time now. The compute platform is the actual battlefield. The array of tanks and airplanes offered by the ARM camp are built in factories that are NOT out of bombing range like American factories of WWII.

Imagine you are a processor architect and have been given a clean sheet of paper to define the next big thing. You have been told that there are three new parameters. The first one is that you have infinite cache SRAM. The second is that you have infinite, off-chip NAND Flash. And the third is that you have a pool of DRAM that is still quite large but has already shrunk by an order of magnitude in size relative to Flash (and is shrinking relative to SRAM) but its cost is FREE. How would you arrange the new architecture? Remember, the price of a loaf of bread in the old USSR was FREE before the breakup.

If you are designing something that will first be in production in 3-4 years and remain as the basis for multiple product spinoffs for an additional 4 years then you push the envelope on those resources that maximize performance/cost and performance/watt. This means that over the lifetime of the chip, Moore’s law will expand the SRAM by a factor of at least 8 over where it is today. NAND Flash is scaling even faster and DRAM will likely scale at half that rate. The beauty of DRAM over its 40-year history is that there was nothing better sitting next to the processor as a cheap, short-term storage of code and data. However, this is fading fast relative to NAND Flash, especially as the flash controllers of the world get smarter in maximizing the life of a bit. This sums up the trend that places NAND and SRAM as the dominating factors driving winners and losers for the next decade. How do Samsung, Intel, TSMC, Toshiba, Sandisk and the rest stack up?

The ramifications of Infinite SRAM and Infinite NAND are probably already incorporated in Intel’s roadmaps for the next 4 years. Many people know that Intel has a business-operating model that they call the Tick-Tock model, where Tick is referred to as a new process technology used on an existing architecture and Tock is a new microarchitecture running on an existing process technology. With SRAM and NAND about to be added in a stacked 3D configuration above the processor – I would like to suggest that the Intel business model will now be effectively known as “3D Tick-Tock.” In 3D Tick-Tock, a variable size of cache or NAND will be stacked to an underlying multi-core CPU to enhance the overall product for mobile, desktop or server applications. The timing of the 3D Tick-Tock product rollouts will be determined by the availability of the latest NAND Flash or Logic (SRAM) process technology. Imagine these new memory cores offering a midlife kicker to the older, more complex processor core at higher prices but same operating and thermal (TDP) power envelopes. And these will be introduced when competitors offer their newest products that are built on one or two generation-old technology. Now Intel’s competitors must think about how they keep up in a whole dimension.

This scenario is why TSMC, Samsung, Sandisk and the ARM Crew must think in a whole new way about competing with Intel. If the Foundries lack world-class process technology in both NAND Flash and Logic and if these same foundries cannot field high performance, small footprint SRAM blocks, then they will not be able to get ARM or any other processor architecture across the goal line in the market segments that Intel chooses to play in.

Samsung’s moment of lift off was available three years ago in early 2009 when the economic world was thought to be close to ending. If they had overpaid for Sandisk, they would have consolidated the NAND Flash industry to themselves before Apple took off and before Intel made the decision to get back in. It was a moment to end Toshiba as a NAND foundry for Apple. Samsung would have owned the 1/2 of the infinite memory architecture playing field that will determine the winners of the Semiconductor market in the coming decade.

FULL DISCLOSURE: I am Long AAPL, INTC, QCOM, ALTR

Advancing Automotive Memory: Development of an 8nm 128Mb Embedded STT-MRAM with Sub-ppm Reliability