Can a 4-member alliance reshape the semiconductor industry?

Semiconductors are ubiquitous in electronics and computing devices, making them essential to developments in AI, advanced military, and the world economy. As such, it is unquestionable that nations attain considerable geopolitical and economic leverage from controlling large portions of the global semiconductor value chain, granting them access to key technological and commercial resources while providing them the ability to restrict the same access from other nations. For this reason, competition between major powers such as the United States and China has largely manifested itself in efforts to attain and restrict access to semiconductor technology. For example, under the CHIPS and Science Act, the United States government offers subsidies to global manufacturers on the condition that the companies do not establish fabrication facilities in countries that pose a national security threat. The United States has also established export controls on advanced semiconductor equipment to China and reached a deal for the Netherlands and Japan to undertake similar measures. China, on the other hand, is a net importer on semiconductors and deems its reliance on competing nations for semiconductor access as a weakness; to counter this, it aims to establish a fully independent value chain, investing billions in its “Made in China 2025” policy to do so.

Perhaps the most ambitious venture to establish greater control over the semiconductor value chain emerged in 2022 under the Biden administration. Prior to the enactment of the , Biden proposed the Chip 4 alliance, a semiconductor collective comprised of the United States, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. The four member states are essential to the semiconductor value chain, with each member specializing in the necessary components to develop semiconductors as a collective. Under the Chip 4, the four member states will engage in coordination for policies on supply chain security, research and development, and subsidy use. The alliance would hold considerable influence on the distribution of semiconductors and can be utilized to significantly limit the chip access of geopolitical rivals. Despite its potential influence, the Chip 4 has yet to be realized, and it is unclear whether the prospective members will make clear commitments towards the alliance. In this article, we will provide a closer examination of the Chip 4 coalition and assess how it may influence the semiconductor industry. We will also observe the numerous challenges that prevent the prospective member states from forming the alliance.

A Closer Look at the Global Semiconductor Value Chain

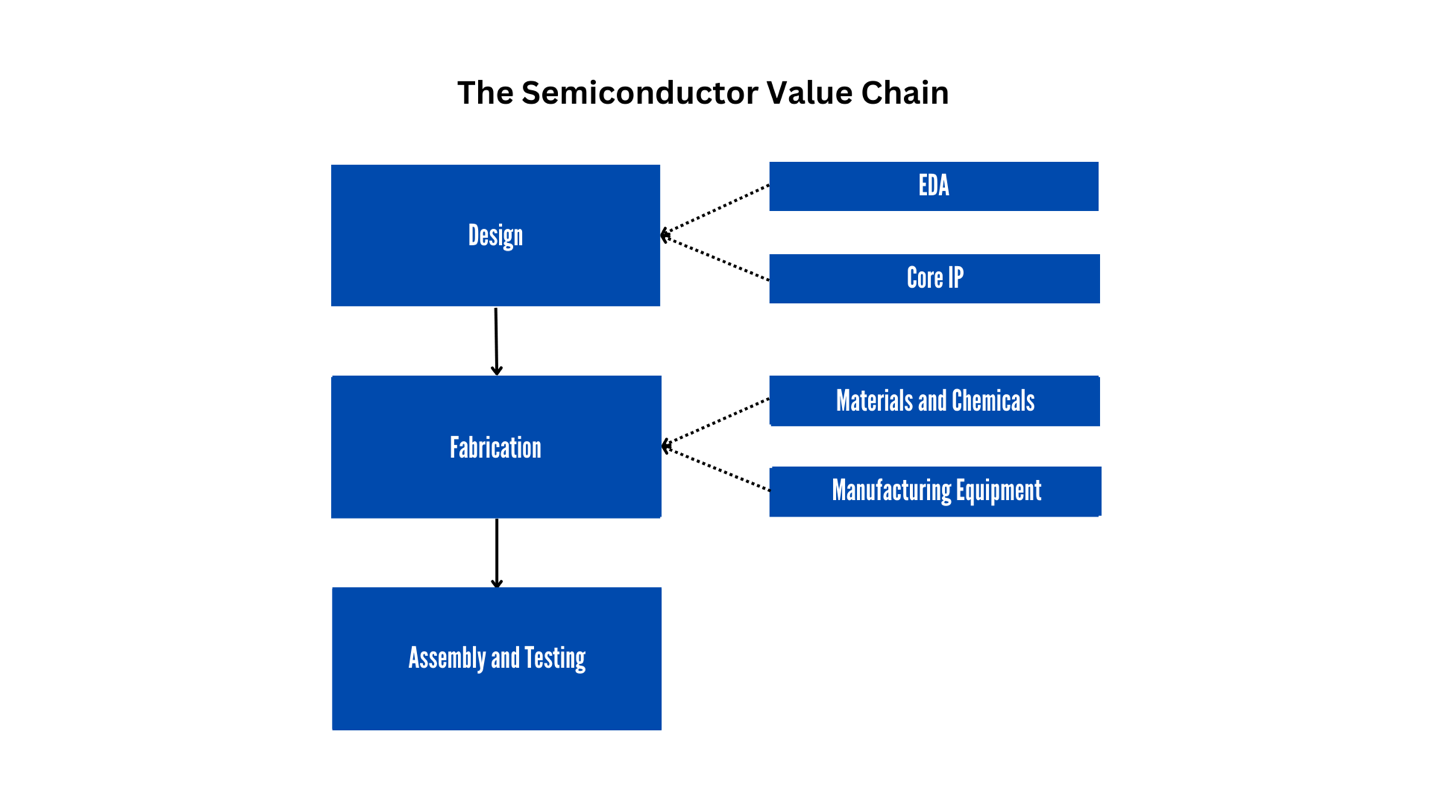

The semiconductor value chain is composed of three central parts: design, fabrication, and assembly. In the design process, the chip architecture’s blueprint is mapped out to fulfill a particular need. The process is facilitated using design software known as electronic design automation (EDA), and intellectual property (Core IP), which serves as basic building blocks for chip design. The semiconductor development process follows in the fabrication stage, where the integrated circuits are manufactured for use. Since these integrated circuits are built within the nano scale, the fabrication process requires highly specialized inputs, both in the form of materials and manufacturing equipment. In the final step, the wafers are assembled, packaged, and tested to be usable within electronic devices. The silicon wafers are sliced into individual chips, placed within resin shells, and undergo testing before being delivered back to the manufacturers.

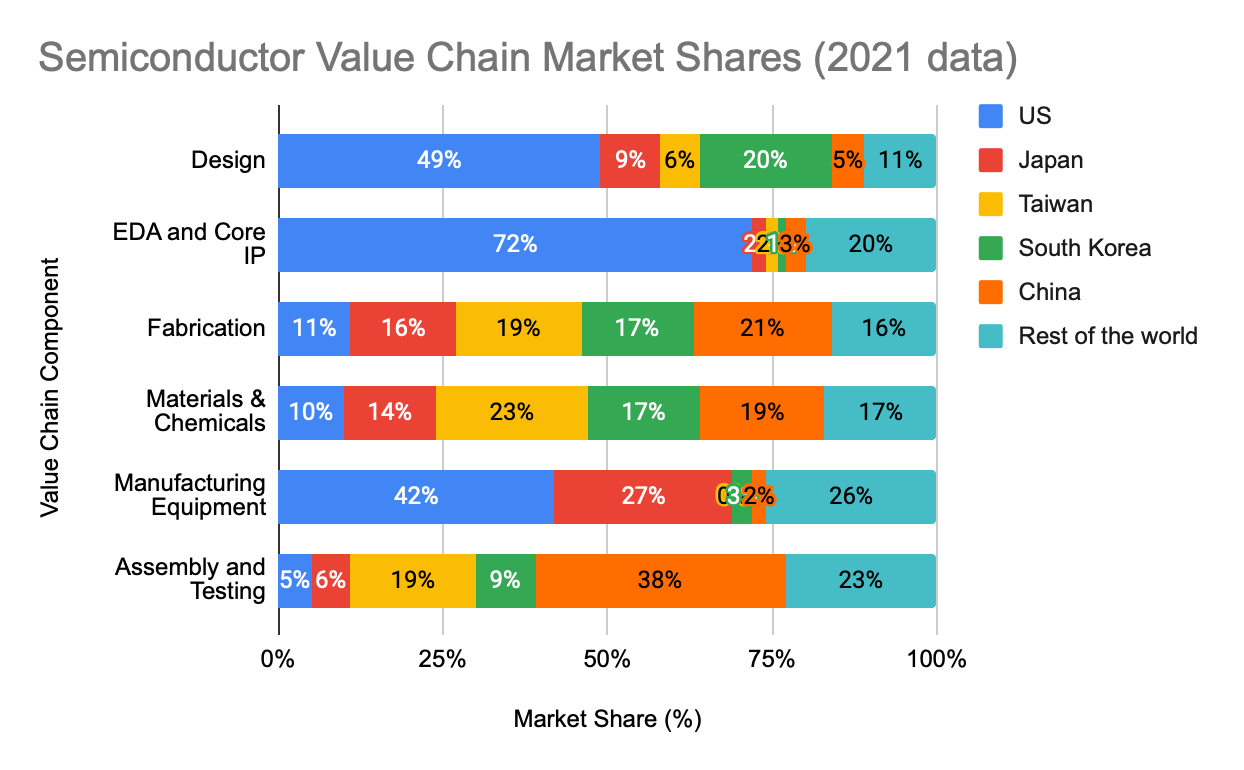

In recent decades, the semiconductor global value chain has become increasingly specialized, with much of the value chain contributions split between the United States and East Asia. United States possesses arguably the most important position within the semiconductor industry, having strong footholds in the design, software, and equipment domains. Its position in the design sector is especially essential, hosting key businesses such as Intel, Nvidia, Qualcomm, and AMD, which account for roughly half of the design market. On the other hand, much of the fabrication market is concentrated in East Asia, where Taiwan and South Korea play major roles. Taiwan and South Korea account for much of the world’s leading-edge fabrication, with TSMC producing the world’s most advanced semiconductors and Samsung following closely behind. In addition, Taiwan holds a well-established ecosystem for semiconductor manufacturing, with numerous sites for materials, chemicals, and assembly. Japan, along with the United States and the Netherlands, account for most of the industry’s equipment manufacturing, providing an essential function to the fabrication process. Lastly, China occupies the largest share of the assembly and testing processes and is also a major supplier of gallium and germanium, two chemicals central to semiconductor manufacturing.

As seen by the distribution of the value chain, the semiconductor industry relies on an interdependent network– no state can source semiconductors without the contributions of other states. Yet, the positioning of nations along the different components of the value chain creates imbalances in the degree of influence a nation has within the semiconductor industry. This, in turn, creates power dynamics that can be leveraged by nations with higher degrees of influence.

Weaponizing the Global Value Chain

Since the global semiconductor value chain operates under an interdependent network of states, states with access to exclusive resources can create chokepoints for rivals, diminishing their semiconductor capacities by withholding essential elements for its production. Hence, export controls operate as central weapons within the realm of global technology development, enabling dominant states to decelerate the growth of rising states.

The United States’ semiconductor-related export control measures against China provide valuable insights on how this principle has affected developments within the industry. In 2019, for instance, the Trump administration enacted export controls against the Chinese telecommunications company Huawei, employing a twofold measure to do so. Firstly, it banned Huawei from purchasing American-made semiconductors for its devices. Secondly, it banned its subsidiary semiconductor company, HiSilicon, from purchasing American-made software and manufacturing equipment. Initially, the measure proved to be ineffective in stunting Huawei’s business operations. Taiwan and South Korea held stronger positions within the semiconductor manufacturing space, and Huawei simply sought their services when American sources were unavailable. The American design firms, which provided blueprints for Huawei chips, outsourced their manufacturing to foreign shores. Here, the export measures damaged American chipmaking firms to a greater extent than it did to Huawei, depriving the domestic businesses of a lucrative client.

However, in an update of the export control policy, the Trump administration extended the export control efforts to third-party suppliers, potentially cutting their access to software, core IP, and manufacturing equipment should they continue to engage in business with Huawei. The United States, by controlling much of the software and core IP sources, could indirectly restrict Huawei’s access to chip design by denying essential inputs to third party design firms. Similarly, its dominant position within the manufacturing equipment industry gave it considerable leverage within the fabrication space, indirectly cutting Huawei’s access to semiconductor manufacturing. By threatening to cut off critical resources for design and fabrication, the United States effectively disincentivized third-party engagement with Huawei. Huawei soon lost crucial access to advanced semiconductors and trailed behind in the smartphone market in the subsequent years, with a report stating that the United States’ efforts cost the company roughly $30 billion a year.

The United States’ policy on semiconductor export control illustrates how having control over fundamental components of the global value chain enables an agent to produce rippling effects downstream. Specifically, the influence the United States was able to exert on China derived from its control over critical chokepoints; the earlier export control measures executed by the United States demonstrated that export controls enacted without sufficient leverage are largely ineffective.

Even so, there are inherent risks associated with a frequent tightening of chokepoints, especially if conducted unilaterally. Since the semiconductor industry is highly competitive and dynamic, companies are frequently producing new innovations within the market. Hence, while withholding critical technology and resources may be effective in the short run, a sustained use of export controls provides opportunities for competitors to produce reliable substitutes and fill the gap within the market. These risks are mitigated by multilateral export controls, where multiple producers along the same chokepoint collectively enact export controls, making it much more difficult for substitutes to be sourced or replaced. Indeed, the Biden administration has increasingly engaged in multilateral efforts in export controls– the Dutch-Japanese-American ban on equipment exports to China is a clear example. More importantly, the proposed Chip 4 alliance provides another critical avenue where multilateral action can be taken.

The World under Chip 4

The stated purpose of the Chip 4 alliance is to provide the four member states with a platform to coordinate policies relating to chip production, research and development, and supply chain management. The United States has outlined the arrangement as one that is fundamentally distinct from its export control policies against China, deeming it as a necessary multilateral coordination mechanism rather than an alliance driven by geopolitical competition. Yet, what would happen if the four member states were to operate under complete coordination and utilize their significant leverage? If the four member states act under a coordinated effort, the Chip 4 would possess unprecedented control over the semiconductor industry, creating an extremely powerful inner circle. In many ways, the formation of the Chip 4 can lead to an extensive weaponization of the global value chain.

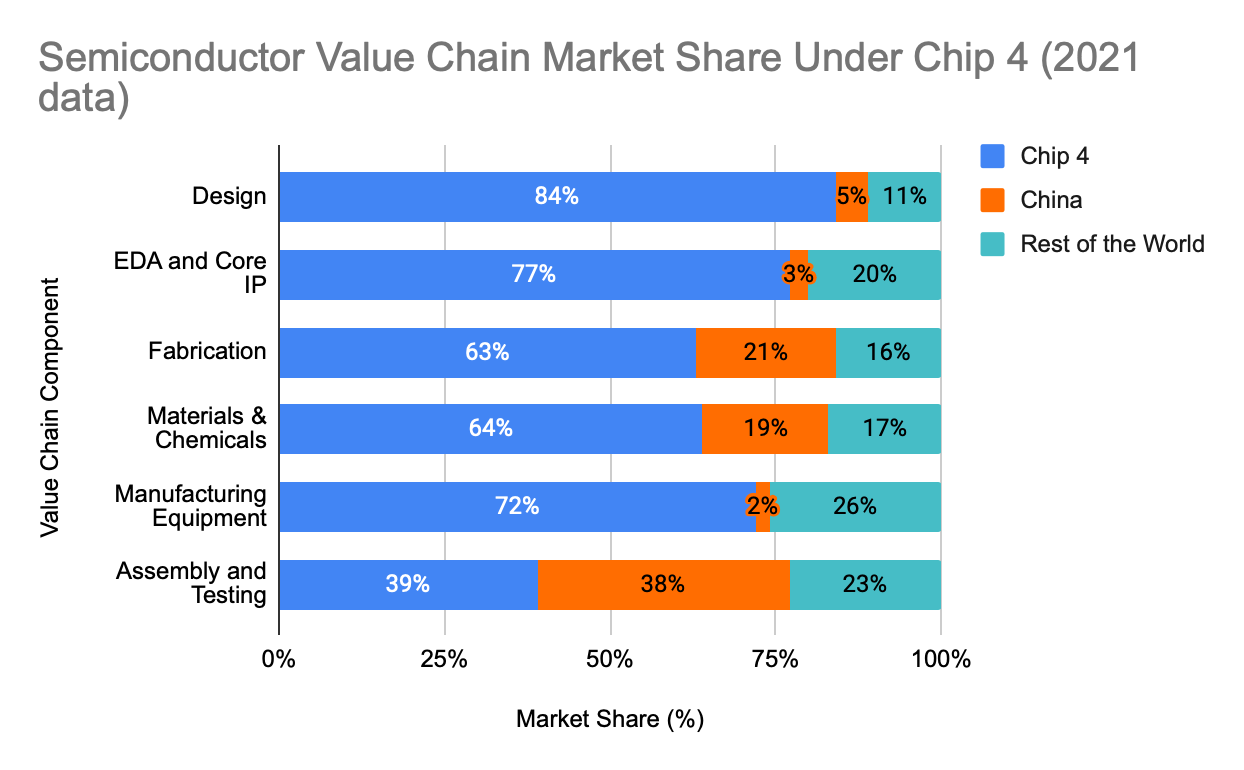

As a collective, the United States, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan would act as the most dominant force within the semiconductor industry, given the capability to exercise significant leverage across almost all areas within the global value chain. When combining their expertise, the Chip 4 would have a majority share in all aspects of the global value chain except for assembly and testing:

As seen above, the Chip 4 could engage in chipmaking processes with minimal engagement from outside sources. More critically, the coordination of resources provides the Chip 4 with a much stronger grasp on chokepoints than the members would have been able to acquire individually. In the design sector, for instance, the United States possesses a 49% share of the market. While significant, the Chip 4 would enhance this market dominance to 84% by combining the capabilities of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan– a multilateral effort to restrict design exports would severely limit the number of reliable substitutes needed for semiconductor production. The Chip 4 would also hold 63% of the market share within the fabrication industry. While a significant figure, it underestimates the actual strength of the Chip 4 within advanced manufacturing; TSMC, Samsung, and Intel have been able to produce logic chips within 10 nanometers, providing the alliance with a near-exclusive access to leading logic technologies. Within the equipment industry, the United States and Japan can still provide essential resources for leading fabrication firms given its concentration in Taiwan, South Korea, and the United States, but the Chip 4’s ability to restrict tooling to outside states could also be used to enhance the position of existing fabrication firms. Imaginably, Netherland’s ASML will also be a close ally to the Chip 4, providing essential equipment with its EUV tooling. Hence, the Chip 4 will inevitably act as a dominant force within the design, fabrication, and equipment industries, greatly shifting the dynamics of the global semiconductor industry.

Conceivably, then, the Chip 4 can be used as an instrument to advance the United States’ technological race against China. Since the Chip 4 holds expertise across almost all aspects of the global value chain, it can rearrange the supply chain in a way that heavily reduces Chinese involvement and access, preventing the country from establishing a strong foothold within the industry. So far, China has been reliant on the technological prowess of its Far Eastern neighbors for its own development– it houses both Taiwanese and Korean fabrication facilities, providing it with access to logic and memory-based manufacturing. Korean companies such as Samsung and Hynix have been especially involved within China’s semiconductor ecosystem, providing a critical access point to the nation’s technological development; Here, China can utilize technological leakages from more advanced fabrication sites to conduct essential knowledge-based transfers. Yet, under American leadership, members of the Chip 4 alliance may opt to reduce further investments within Chinese borders, effectively stalling Chinese progress.

Given the advantages the members would attain by forming a coalition, the prospect of establishing the Chip 4 appears highly attractive. However, the current state of the alliance suggests that its formation remains a far-reaching ideal. Although plans of a coalition have been in discussion since March of 2022, the prospective member states have been slow to set the groundwork for a coordinated policy. So far, only two meetings have been held to discuss the nascent coalition. The first occurred in September of 2022 and was attended only by working-level officials. A more recent meeting occurred virtually in February of 2023 between senior officials, though more concrete plans for the coalition have yet to be laid out. Despite its salient benefits, the establishment of the coalition presents significant risk factors and challenges for its member states to confront, prompting a more cautious approach to the alliance. These pressing obstacles serve as the greatest source of inertia for the alliance’s progression.

The Geopolitical Challenge

The principal obstacle to a formal declaration of Chip 4 membership stems from the geopolitical implications it carries. Since the Chip 4 can be leveraged to impede China’s semiconductor development, a commitment towards the alliance will undoubtedly be interpreted antagonistically by the Chinese government. For Asian members who have complicated economic and geopolitical ties to China, this can serve as a significant barrier to entry. Unsurprisingly, the Chinese government has voiced concerns against the coalition, with a spokesman specifically urging the South Korean government to reconsider its long-term interests before making formal commitments. Diplomatically, South Korea has maintained stronger relations with China compared to other Chip 4 states and therefore has a weaker interest in slowing China’s semiconductor progress. While Japan and Taiwan have demonstrated strong interest in following the United States’ multilateral initiative even at the cost of worsening diplomatic ties with China, South Korea has indeed been more reluctant to act– of the four member states, South Korea was the last to commit to a preliminary meeting discussing the Chip 4. Within the semiconductor industry, South Korea’s tie to the Chinese market is significant; Samsung and Hynix have built numerous fabrication facilities in China, and the Chinese market accounted for 48% of South Korea’s memory chip exports in 2021. In addition, the Chinese government has demonstrated a willingness to engage in retaliatory action when its interests are placed under threat. In 2017, for instance, the Chinese government implemented policies to restrict trade with Korea as a response to its adoption of THAAD anti-missile technology. More recently, it restricted the export of gallium and germanium following the Dutch-Japanese-American export ban on semiconductor equipment. As such, any steps taken to restrict Chinese access to technology will likely lead to an escalation of trade restrictions, inflicting high economic costs on all involved parties. Attaining membership in the Chip 4 therefore carries a fundamental risk, and South Korea appears to be the most disinclined to act under such circumstances.

There are also geopolitical tensions among the prospective Chip 4 members that makes a formal coalition difficult to establish. While Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan each have strong diplomatic ties with the United States, the relationship between the East Asian member states tends to rest on more tentative grounds. South Korea and Japan’s foreign relations have not fully recovered from their wartime past, which remains as a source of diplomatic friction; in 2018, South Korea’s Supreme Court ruled for Japanese companies to compensate for its forced usage of Korean labor in their wartime factories, prompting the Japanese government to retaliate in kind by restricting the export of essential semiconductor-related chemicals to Korea. On a different note, a South Korean official raised questions about establishing a formal alliance with Taiwan, seeking assurance from the U.S. government that Taiwan’s membership does not preclude a violation of the One China policy. These concerns indicate that diplomatic tensions concerning the Chip 4 are not only manifesting externally, but internally as well. Clearly, the United States must play a role in ameliorating these tensions for a seamless establishment of the Chip 4. The arrangement of the trilateral summit between the United States, Japan, and South Korea in August of 2023 demonstrates the United States’ willingness to forge stronger ties between the Asian states, but it remains to be seen whether its efforts will be sufficient for the formation of the chip alliance.

The Business Challenge

When discussing the Chip 4, some have likened the alliance to OPEC of the oil business, observing that the centralized coordination of the semiconductor industry among the 4 member states could produce a cartel-like presence within the market. While there may be some similarities between the two coalitions, it is important to point out key differences: the coordination efforts of the Chip 4 would be conducted for the interest of national security, coming at the expense of private firms by depriving them of essential markets. The conflict between national security and business interests thus serves as another point of friction for the Chip 4’s establishment. Already, American firms have demonstrated increasing resistance at the tightening of sanctions against Chinese firms. When the U.S. announced export bans in 2022, Lam Research, Applied Materials, and KLA, U.S.-based equipment manufacturers, had stated that they could lose up to $5 billion in revenue from China. Following the enforcement of the bans, Applied Materials came under criminal probe for supplying shipments to China, reportedly selling to Chinese fabrication firms under disguised third parties. The realization of the Chip 4 would likely signify an escalation of trade restrictions against China, meaning businesses that have typically relied on Chinese consumption for its revenue would have much to lose from the maneuver. A sustained exclusion of exports to China would thus be received negatively by semiconductor firms, which rely on its large market for its businesses.

One must also consider the possible effects the formation of the Chip 4 may have on competition and chipmaking innovation. A coordination of semiconductor manufacturing would be a source of concern for leading fabrication firms, who may have concerns about the prospect of sharing technologies with potential rivals. As noted by U.S. government officials, the South Korean leadership has expressed apprehensions that companies such as TSMC and Samsung may be encouraged to engage in knowledge exchange. Similarly, there are worries that the Chip 4 initiative may be used for the United States to place their chipmaking firms under more favorable conditions within the market. Indeed, if the semiconductor firms were to engage in explicit coordination efforts regarding manufacturing and distribution, some firms would undoubtedly benefit more than others; it would be a challenge for the Chip 4 to reach an agreement that complements the competing interests of all governments and private firms. More importantly, the introduction of governmental intervention could greatly reduce the competitiveness of the industry, stalling the pace of innovation in the process. Here, an overextension of governmental control could reshape the semiconductor industry for the worse, depriving the industry of its most valuable innovations. To alleviate these business concerns, the Chip 4 must assure firms that it will strive towards geopolitical objectives while maintaining the integrity of the industry’s operations and practices. A failure to do so will be highly costly not only to the industry, but the various other industries that rely on semiconductor development.

The Future of Chip 4

Overall, it remains uncertain what will become of the Chip 4. The two preliminary meetings indicate that there is a nascent interest in the coalition among the Asian states, but the inner mechanisms of the alliance are yet to be fully articulated. Additionally, the scarcity of official statements regarding the alliance indicates that the dialogue surrounding it remains highly tentative; These developments suggest that the Chip 4’s formation will not be realized in the coming years but may take much longer to complete. In truth, if the Chip 4 were to reshape the semiconductor industry as outlined above, it would be wise for the member states to approach the opportunity with careful deliberation. While a potent concept, the prospective alliance remains held back by the geopolitical and business concerns that greatly damage its appeal. The threat of an escalation of trade-related conflicts, coupled with the challenges of business coordination, raise questions about the effectiveness of the coalition. The American leadership must assure that the benefits of the alliance clearly outweigh the risks before any substantial steps will be taken by other prospective members.

Even if the Chip 4 fails to form, however, the very discussion of its concept signifies a decisive shift in the state of the industry: geopolitical concerns have leaked into the semiconductor world, fundamentally transforming business practices across regions. The United States will continue to tighten its semiconductor exports to China and prompt many of its allies to engage in similar efforts. China will continue to look for avenues of innovation that circumvent its rival’s technology restrictions. The remaining players within the field will find it increasingly difficult to engage with one global power without displeasing another. As technological advancements raise the stakes of attaining semiconductor access, the industry will likely split even in the absence of the Chip 4. With or without it, the globalized era of chipmaking is nearing its end, ushering in a fragmented landscape in its stead.

Also Read:

The State of The Foundry Market Insights from the Q2-24 Results

Application-Specific Lithography: Patterning 5nm 5.5-Track Metal by DUV

TSMC vs Intel Foundry vs Samsung Foundry 2026