My PhD thesis is titled The Design of a Network Filing System. Yes, that was a research topic back then (and yes, we did call them filing systems not file-systems). One big chapter was on access controls. There are several problems with designing an access control system:

My PhD thesis is titled The Design of a Network Filing System. Yes, that was a research topic back then (and yes, we did call them filing systems not file-systems). One big chapter was on access controls. There are several problems with designing an access control system:

- it needs to be possible to implement it efficiently

- it needs to be flexible enough to provide the controls that the organization requires

- it needs to be comprehensible to the people who have to set up the controls

These are hard goals to reconcile. When I worked at VLSI Technology I was responsible for all the data management infrastructure and I soon discovered that the elegant (to me!) access control systems that a software engineer might dream up were not really usable by design engineers. They only wanted very basic capability, namely that most stuff should be shareable and alterable, except they also wanted the capability to take a snapshot of the design and keep it in a form that could never be changed. I invented something I called a read-only-library (actually a large file containing all the smaller files that made up the snapshot). This was especially useful at tapeout to capture the precise design that was taped-out and ensure nobody could change it (since then it would not match the masks), and for standard cell libraries that were also “released” in specific versions. That was about as far as IP went in the early 1980s when a state-of-the-art chip was 10,000 gates.

Now we are in a different world. As a couple of the speakers at SEMI’s ISS this week stated, the semiconductor industry is becoming a dumb-bell, with one end being very large companies with broad IP portfolios (think Broadcom say, or Synopsys) and at the other are tiny companies with a business of selling one product, either as IP or a chip. And nothing really in-between. Those large companies with huge IP portfolios have blocks that are generic and others that are crown-jewels. They need very different access controls since some products (an LTE-modem say) should be restricted on a need-to-know basis to ensure that a random engineer leaving for the competition hasn’t had access to it (unless working on the product, obviously) but others (a standard cell library perhaps) need to be widely available to every design engineer.

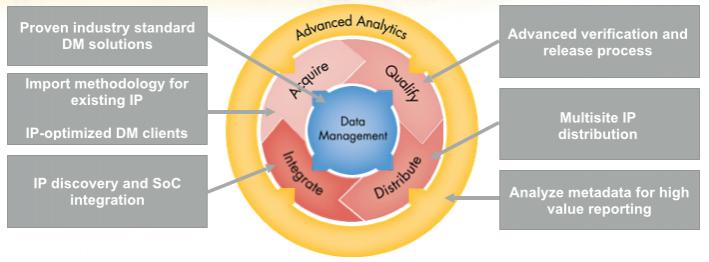

These days we have powerful source control systems such as git and subversion. But these are designed for software projects and don’t really map directly onto the capabilities that are required for managing the IP lifecycle or the design of semiconductors with myriad views, hierarchy and a variety of requirements that don’t map well onto software (you can see the netlist but not the layout). This is where Methodics comes in, providing the capabilities for managing the IP lifecycle in a layer between the basic underlying data management system and the designers themselves.

These days we have powerful source control systems such as git and subversion. But these are designed for software projects and don’t really map directly onto the capabilities that are required for managing the IP lifecycle or the design of semiconductors with myriad views, hierarchy and a variety of requirements that don’t map well onto software (you can see the netlist but not the layout). This is where Methodics comes in, providing the capabilities for managing the IP lifecycle in a layer between the basic underlying data management system and the designers themselves.

For example, engineers integrating an IP block (say that LTE-modem) need one level of access, whereas engineers that are designing that block need another level of access. In particular, the first group of engineers need read-only access to some subset of the views of the block, whereas the designers of the block need to be able to alter it and fix bugs in it and create releases of it.

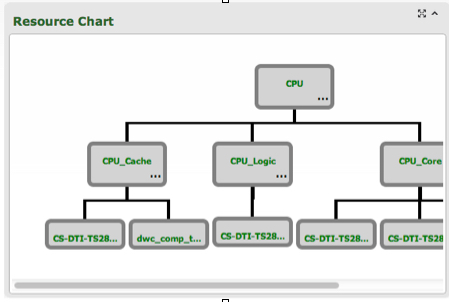

At the IP level there is some hierarchy in the sense that large IP blocks will pull in smaller IP blocks. For example, an Ethernet controller is an integration of a MAC (digital logic) and a PHY (largely analog) probably designed by different groups. It needs to be possible to control access to the high level (designers can alter it, for example) without automatically granting the same access to the lower-level IP blocks (the integration engineers cannot change the MAC).

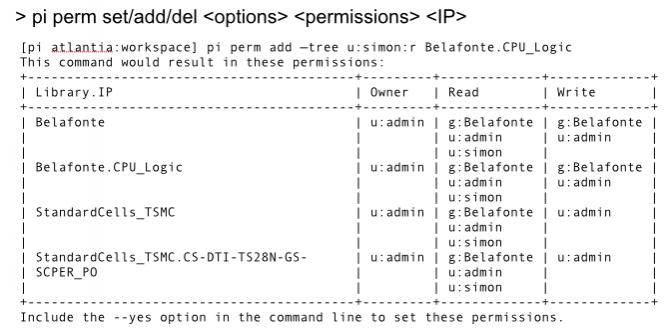

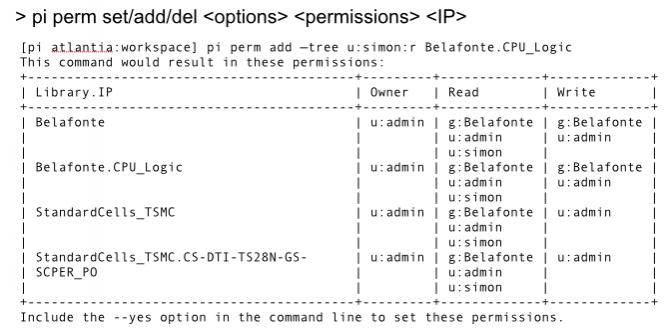

Methodics ProjectIC provides access control commands that provide this level of flexibility through the pi permcommand. It is possible to do things like:

- add a new user to the project with read access to everything

- selectively remove access to lower-level IP blocks

- preview what permission changes a particular command would make without making the changes, to check that no unwanted changes will happen

- construct complex access controls that are not wholly hierarchical (a contrived example: allow access to the US, deny it to California in general, but permit it for Palo Alto)

Read the white paper on IP permissions management here

More articles by Paul McLellan…

Comments

There are no comments yet.

You must register or log in to view/post comments.