On November 7 last year, Henry M. Paulson, Jr., Chairman of the Paulson Institute and former Secretary of the US Treasury gave a speech in Singapore about the growing tension between the United States and China and warned that “an economic iron curtain” is a very real possibility as a result of a decoupling between the United States and China. Chinese as well as foreign media have since then written about a possible US-China decoupling resulting in a variety of opinions about the matter.

“Other countries are being forced into an unwelcome choice. In a win-lose world, you are either with America or you are with China.” – Edward Luce, Washington columnist and commentator for the Financial Times; Financial Times, December 20

“It is utterly unrealistic to uncouple China and the US economically. The two economies are symbiotically connected and are too interdependent to be pried apart.” – Sourabh Gupta, senior fellow at the Washington-based Institute for China-America Studies; Xinhua, June 4

“The trade war from our side is primarily about decoupling China from the US supply chain. I get it. But these policies that Trump is pursuing also gives the rest of the world an argument to decouple from the US.” – John Scannapieco, shareholder Nashville office Baker Donelson law firm; Forbes, June 26

“Decoupling could be seen as ‘strategic blackmail’ for Washington to try to prevent China from growing stronger.” – Li Xiangyang, director National Institute of International Strategy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences; South China Morning Post, July 7

“Beijing could work more with its Asian neighbors to prepare for a possible decoupling with the United States.” – Sun Jie, Researcher Institute of World Economics and Politics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences; South China Morning Post, July 7

Mr. Paulson also reflected on his own speech in February this year when he addressed the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS): “Technology is an integral part of business success, blurring the lines between economic competitiveness and national security. The result is that, after forty years of integration, a surprising number of political and thought leaders on both sides advocate policies that could forcibly de-integrate the two countries … We need to consider the possibility that the integration of global innovation ecosystems will collapse as a result of mutual efforts by the United States and China to exclude one another. [This] could further harm global innovation, not to mention the competitiveness of American firms around the world. But more than that, I am convinced that it has the potential to harm the United States in ways that too few people in Washington seem to take seriously: They’re focused on finding ways to hurt China and attenuate its technological progress in advanced and emerging industries. But they’re less focused than they should be on what that effort might mean for America’s own technological progress and economic competitiveness.”

The potential damage the US government’s actions in the trade war could do to global innovation ecosystems as well as American companies is particularly relevant in the semiconductor industry. The two most prominent targets of the US government’s actions have been ZTE and Huawei. After Huawei was put on the US Department of Commerce’s Entity List in May, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce announced it would publish its own list of ‘unreliable entities’. Although no such list has been published yet, American semiconductor companies such as Qualcomm and Intel, who had already cut off their supplies to Huawei, could potentially be targeted.

But even without being listed as an ‘unreliable entity’ by the Chinese government, the consequences of US government actions could hurt US semiconductor companies. A staggering 67% of Qualcomm’s revenue comes from China, for Micron this is 57%, and for Broadcom 49%. These three companies’ combined revenue from China was US$ 42.8 bn in 2018. It is no surprise that the American Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) told the Trump administration that the sanctions against Huawei risked cutting off its members from their largest market and hurting their ability to invest. US-based Qorvo indicatedthat sales to Huawei accounted for 15% of its total annual revenue (US$ 3bn) and US company Lumentum said that Huawei accounted for 18% of their revenue in Q1 2019.

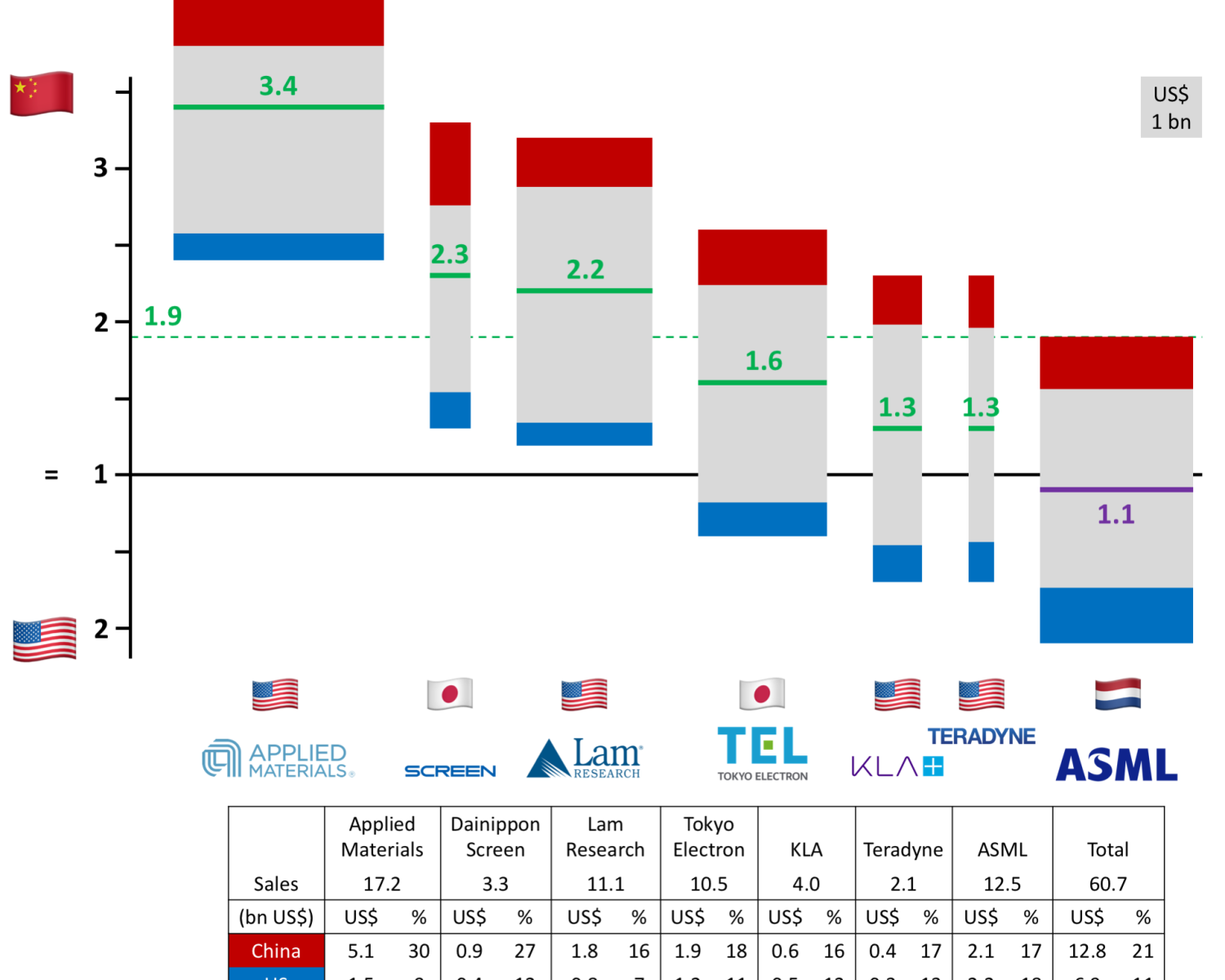

Especially in an industry where R&D is not only necessary but also very costly, losing revenue from China will hurt the technological development and competitiveness of American firms. To get an idea about the potential impact of a US-China decoupling in the semiconductor industry, I analysed semiconductor companies’ revenue shares from the US and China. Looking at the annual reports of seven of the largest semiconductor equipment companies, all but one (Dutch lithography equipment maker ASML) sell more to China than to the US (see Figure 1). The China-US ‘sales balance’ for Applied Materials shows that their revenue from China is 3.4 times as much as their revenue from the US.

For the other three American (Lam Research, KLA and Teradyne) and two Japanese (Dainippon Screen and Tokyo Electron) equipment makers, the sales balance also favours China. One possible explanation that ASML’s revenue from the US is (a little) more than their revenue from China, is that their most expensive (EUV) equipment is used for the most advanced technology nodes. It is likely that they sell these more to the leading chipmakers (such as Intel in the US) than to (less advanced) foundries in China.

For the combined revenue of these seven equipment makers (US$ 60 bn), the China part is 1.9 times as much as that from the US. Sales to China and the US represent about one third of their total sales on average, South Korea and Taiwan (and to a lesser extent Japan) being the most important other sales regions for these companies.

Figure 1: China-US sales balance semiconductor equipment

I did the same exercise for eight of the biggest semiconductor suppliers in the world (see Figure 2). For the selected companies, six from the US (Qualcomm, Micron, Broadcom, Texas Instruments, Nvidia and Intel), one from the Netherlands (NXP), and one from South Korea (SK Hynix), the numbers are even more striking. US-based Qualcomm’s China revenue is more than 25 times as much as its US revenue.

Although the other companies’ sales balance does not even get close to Qualcomm’s, another four of these companies sell more than 3 times as much to China as they do to the US. Actually, for all these eight major semiconductor suppliers their China sales is more than their US sales.

For the combined revenue of these eight semiconductor suppliers (US$ 218 bn), the China part is 2.3 times as much as that from the US. For these companies, sales to China and the US represents on average 60 percent of their total sales. Two (non-US) companies that are often mentioned in the semiconductor suppliers top 10 are not included in this analysis. South Korea’s Samsung is not included because it does not present a geographical distribution for its semiconductor business (US$ 77.2 bn) in its annual report. Taiwan-headquartered TSMC is left out as it is the only pure play foundry among these companies.

Figure 2: China-US sales balance semiconductor suppliers

It is no surprise that for all global leaders in the semiconductor industry both China and the US are extremely important markets. What becomes clear here though, is that for 14 out of 15 of the largest semiconductor companies in the world, including all 10 American companies, their sales in China is (sometimes much) more than their sales in the US.

For the 10 American semiconductor companies included in this analysis, their combined revenue from China (US$ 79.3 bn) is 2.8 times as much as their combined revenue from the US (US$ 28.1 bn).

The Chinese government has made no secret of its ambitions to further develop the domestic semiconductor industry. For instance, by establishing the China Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund (CICIIF or ‘Big Fund’) in 2014 and setting ambitious targets for the semiconductor industry in the “Made in China 2025” plan. With setting up the Big Fund, the Chinese government envisioned spending more than US$ 160 bn over 10 years to stimulate developments in semiconductor design and manufacturing and one objective of Made in China 2025 is to increase China’s self-sufficiency in chip production to 40% in 2020 and 70% by 2025. Ding Wenwu, President of the Big Fund, already acknowledged 1.5 years ago that this catching up will not be an easy task: “How can one overtake the front-runners when lagging so far behind? Not to mention the leaders are trying very hard to keep their position.”

Looking at the 2018 data, the only conclusion can be that there is still a long way to go for China to reach the desired levels of domestic chip production. IC insights calculated that total chip production in China by Chinese headquartered companies accounted for only 4.2% of the domestic demand in 2018.

Adding the production by foreign companies in China, this number rises to 15.5%. More than 70% of the chips made in China are made in foreign companies’ fabs. Being the largest consumer of chips, China is still very much dependent on importing them. Even with chip production of foreign companies in China included, it will be very challenging to achieve the ambitious goals of self-sufficiency.

In the semiconductor industry’s globally integrated network, policies aimed at decoupling will not help anyone. China needs fabs of foreign (including US) companies to reach its targets of ‘domestic’ production. The semiconductor equipment leaders are American, Japanese and Dutch companies, and increasing production without equipment from these countries seems impossible. On the other hand, these companies also need their revenue from China to be able to invest in R&D and keep innovating. This is even more true for the largest semiconductor suppliers in the world such as Intel, Micron, Qualcomm, Broadcom and Texas Instruments. SIA mentioned in their April 2019 report Winning the Future – A Blueprint for Sustained US Leadership in Semiconductor Technology: “The US semiconductor industry already invests heavily in its own research and development to stay competitive and maintain its technology leadership. Nearly one-fifth of US semiconductor industry revenue is invested in R&D.”

Many (most) of the largest semiconductors suppliers in the world are American companies, but any policy that diminishes their China revenue will definitely hurt their competitiveness. According to the SIA report, “Semiconductors are America’s fourth-largest export, contributing positively to America’s trade balance for the past 20 years. More than 80 percent of revenues of US semiconductor companies are from sales overseas. Revenue from global sales sustains the 1.25 million semiconductor-supported jobs in the US, and is vital to supporting the high level of research and development necessary to remain competitive.”

Banning US companies from doing business with Chinese semiconductor companies will indeed delay the development of the semiconductor industry in China. But that’s just one side of the story. It will also hurt American (and other) companies’ competitiveness, as Mr. Paulson argued in his speech about a US-China decoupling and the possibility of an ‘economic iron curtain’. I hope this article gave some quantitative insights on how much the US and China, and all countries in the global semiconductor value chain, are dependent on each other to keep achieving technological progress. So please allow me to end with a quote by Ken Wilcox, Chairman Emeritus of Silicon Valley Bank, one of the experts interviewed in the (highly recommended) film “Trump’s Trade War” by Frontline and NPR:

“If your goal is to stop China from advancing, you’re not going to accomplish that anyway. Because they’ll just innovate around you.

Why would you want to stop anybody from making progress? … The better goal is for us to spend time on becoming more powerful ourselves.”

Share this post via:

TSMC N3 Process Technology Wiki