Siemens recently released a white paper on a methodology to enhance test coverage for designs with tight DPPM requirements. I confess when I first skimmed the paper, I thought this was another spin on fault simulation for ASIL A-D qualification, but I was corrected and now agree that while there are some conceptual similarities this proposal describes a quite different purpose. The intent is to extend coverage accomplished through ATPG test vectors with carefully graded functional vectors in support of strengthening coverage and minimizing DPPM, particularly around areas that are missed by ATPG.

Why is this needed?

Just as large designs are becoming harder to verify, they are also becoming harder to test in manufacturing. SoCs have always needed PLLs for clock generation and now incorporate mixed signal blocks for sensor and actuator interfaces, all functions that are inaccessible to conventional DFT. Just think of all the mixed-signal speech, image, IMU, accelerometer and other real-world sensors we now expect our electronics to support.

Many SoCs must ensure very low failure rates. SD memory subsystems support warm-data caching in datacenters and must guarantee vanishingly small error rates to support cloud service pricing models. Cars too, beyond meeting ASIL A-D certification levels, also depend on very low error rates to minimize expensive recalls. None of these requirements is directly related to safety but they are very strongly related to profitability for the chip maker and the OEM.

Enhancing coverage

ATPG will mark anything it couldn’t control/observe as untestable. Strengthening coverage depends on finding alternate vectors to address these untestable faults, where possible. This is accomplished in the Siemens flow by grading vectors produced during design verification against faults injected into the design. Clearly the aim is to find a very compact subset of vectors since these tests must run efficiently on ATE equipment. This method uses a fault simulator, also used in automotive safety verification (hence my initial confusion), for functional fault grading. Rather than checking the effectiveness of safety mechanisms, here we want to control and observe those “untestable” faults from the ATPGP flow.

Importantly, while ATPG can’t access the internals of 3rd party IP, around AMS blocks or other cases, functional verification is setup to be able to exercise these functions in multiple ways, through boot sequences, mixed signal modeling and other possibilities. Maybe you can’t test internal nodes in these blocks, but you can test port behavior, and that’s just what you need to enhance DFT coverage.

Methods and tools

Fault grading proceeds as you would expect. You inject faults at appropriate points, ideally for a range of fault models, from stuck-at to timing delay faults and more. The paper suggests injecting faults at module ports since these most closely mirror controllable and observable points in testing. They point out that while you could inject faults on (accessible) internal nodes, that approach will likely lead to overestimating how much you improved coverage, since ATE equipment cannot access such points.

They suggest using the usual range of fault coverage enhancement techniques. First use formal to eliminate faults that are truly untestable, even in simulation. Then use simulation for blocks and smaller subsystems. And finally, use emulation for large subsystems and the SoC. Used in that order, I would suggest. Address as many untestable faults as you can at each stage so that you have a smaller number to address in the next stage.

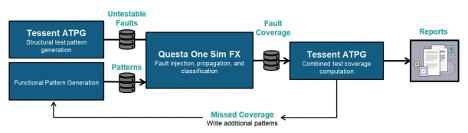

Siemens integrated tool flow and experiment

The paper works with a tool flow of Tessent™ ATPG and Questa One Sim FX . Using this flow, they were able to demonstrate test coverage improvement by 0.94% and fault coverage improvement by 0.95%. These might not seem like big improvements but when coverage is already in the high 90s and you still need to do better, those improvements can spell the difference between product success and failure.

Good paper. You can download it HERE.

Share this post via:

Comments

There are no comments yet.

You must register or log in to view/post comments.