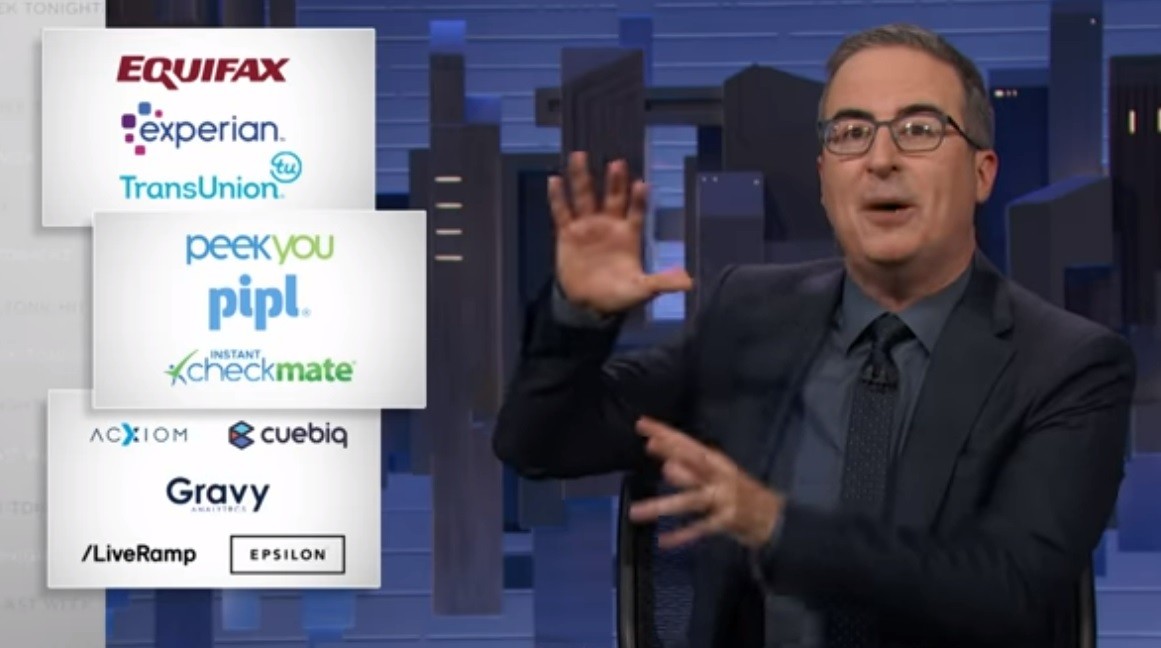

The same week that John Oliver took on the topic of privacy on his HBO program “Last Week Tonight,” one of the leading automotive data brokers – Otonomo – became the target of a class action lawsuit in California. While Oliver detailed the creepiness of everyday privacy violations on computers, mobile phones, and connected televisions, the lawsuit highlighted the privacy-compromising possibilities of connected cars.

Lawyers from Edelson PC have alleged that Otonomo collects location data on thousands of California residents resulting in a violation of the California Invasion of Privacy Act. The implications are sobering for both car makers and the dozen or more vehicle data brokers that have given form to this new market sector.

Otonomo rose to prominence with a billion-dollar SPAC in 2021. The special purpose acquisition corporation (SPAC) merger in August of last year valued money-losing Otonomo at $1.09B with a stock price of $8.31 a share. The gross proceeds of the SPAC were $255.1M for Otonomo, the stock price of which today stands at less than $2.

Otonomo was not alone in SPAC-ing in 2021. Fellow data broker startup Wejo concluded its own successful SPAC merger following Otonomo’s. Like Otonomo, Wejo’s stock has plunged since going public and the most recent quarterly results – reported March 31 – show an enormous $67.7M net loss with a further $100M+ loss anticipated for 2022.

Enthusiasm for “monetizing” car data was inspired by a notorious 2016 McKinsey report which estimated the value of car data at between $450B and $750B. What many readers of the report ignored was the portion of that forecasted value that was derivative or indirect. These literal interpreters and their car company enablers have sought to directly monetize vehicle data by literally selling it to growing networks of service providers and retailers also seeking to cash in.

The McKinsey report unleashed a gold rush among startups and established players seeking to unlock those billions. Car companies themselves got in on the act with companies such as Volkswagen, Audi, and Stellantis proclaiming that they would soon derive more value and revenue from car data than they would from selling vehicles.

Companies including Caruso and Xapix emerged alongside Wejo and Otonomo. All of these companies began collecting data from a range of sources including direct access to vehicle data from car makers (GM and Volkswagen sharing data with Wejo) as well as data derived from aftermarket devices and connected car smartphone apps.

The dismal reality is now setting in that not only is it difficult to extract value from car data (which often needs to be “cleaned up” and anonymized), it may also be illegal if not done properly. Data monetizers need expertise to extract value from vehicle data and they also need consumer consent.

Most early vehicle data applications derived first and foremost from vehicle tracking – i.e. the basic business of locating vehicles which may be in transit, making deliveries, or stolen. Of late, the emphasis has shifted toward vehicle diagnostics and driver behavior for service scheduling and insurance applications, respectively.

Most rental agreements and new car sales agreements include language regarding customer consent – but consent is often obtained as part of a fairly opaque process. The consumer scans past the small print that gives the dealer or auto maker the right to collect and resell vehicle data. This appears to be the case in the Otonomo class action.

Vice.com reports: “The plaintiff in the case is Saman Mollaei, a citizen of California. The lawsuit does not explain how it came to the conclusion that Otonomo is tracking tens of thousands of people in California.

“Mollaei drives a 2020 BMW X3, and when the vehicle was delivered to him, it contained an electronic device that allowed Otonomo to track its real-time location, according to the lawsuit. Importantly, the lawsuit alleges that Mollaei did not provide consent for this tracking, adding that ‘At no time did Otonomo receive—or even seek—Plaintiff’s consent to track his vehicle’s locations or movements using an electronic tracking device.’

“More broadly, the lawsuit claims that Otonomo ‘never requests (or receives) consent from drivers before tracking them and selling their highly private and valuable GPS location information to its clients.’ The lawsuit says that because Otonomo is ‘secretly’ tracking vehicle locations, it has violated the California Invasion of Privacy Act (CIPA), which bans the use of an ‘electronic tracking device to determine the location or movement of a person’ without consent.”

Otonomo says it protects customer privacy and obtains consent. Vice previously published an account of a 2021 investigation which revealed that data obtained from Otonomo could be used “to find where people likely lived, worked, and where else they drove.”

There is little doubt that vehicle data has value. Whether the value of that data amounts to hundreds of billions of dollars is debatable. What is clear, though, is that the organizations looking to cash in need consumer consent.

The Alliance for Automotive Innovation, representing the interests of foreign and domestic auto makers, has a privacy policy on its Website with two principles:

Participating automakers commit to:

1. Providing customers with clear, meaningful information about the types of information collected and how it is used

2. Obtaining affirmative consent before using geolocation, biometric, or driver behavior information for marketing and before sharing such information with unaffiliated third parties for their own use

Andrea Amico, founder of Privacy4Cars, a data privacy advocacy group, noted that the automotive industry continues to fall well short of these objectives. Amico said that auto makers seeking to access vehicle data need to provide:

1. A clear, prominent notice

2. A method for the customer to provide affirmative consent

3. An easy-to-use method for the customer to opt out

4. A process for managing a change in vehicle ownership

5. A process for erasing data

6. The one exception might be data related to the operation of a safety or emergency response system – as well as data reporting required by regulatory authorities. Of course, internal use of data by an auto maker is to be distinguished from data used by, sold to, or shared with third parties.

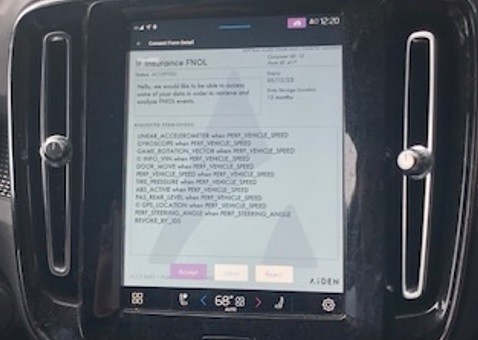

As an example, Aiden is a vehicle data startup focused on the growing number of cars arriving in the market equipped with the Android Automotive operating system. Last week and at the Consumer Electronics Show in January, Aiden demonstrated a first notice of loss (FNOL) car insurance application with an in-dash consumer consent element.

The application provides a complete in-dash display of all data to be shared with the insurance company with the option for the consumer to “Accept,” delay a response: “Later,” or “Reject.” This is a clear and prominent display requiring an affirmative response (which could also be a rejection).

SOURCE: In-dash screen shot of Aiden FNOL consent form.

Current auto maker and, by extension, new car dealer privacy policies are inadequate to fulfill the requirements of prominent notification, affirmative consent, customer control, and ownership transfer. Under current conditions, the Privacy4cars representative suggested that the Otonomo class action is not likely to be the last.

Car makers, rental car companies, and operators of car sharing programs need to review their policies for data management and privacy. We know it isn’t easy to monetize vehicle data – as demonstrated by two money-losing SPACs. Now we know it also requires consent.

Also Read:

ITSA – Not So Intelligent Transportation

OnStar: Getting Connectivity Wrong

Tesla: Canary in the Coal Mine

Share this post via:

TSMC N3 Process Technology Wiki