GlobalFoundries’ (GF) acquisition of MIPS in 2025 wasn’t a nostalgic move to revive a legacy CPU brand. It was a calculated step into one of the most lucrative frontiers in semiconductors: AI, high-performance computing (HPC), and datacenters. As Nvidia, AMD, Intel, and hyperscalers embrace chiplet architectures, GF is betting that owning CPU IP will secure it a central role in the modular compute era.

Chiplets Reshape the Datacenter

The shift to chiplets in datacenters is now undeniable. AI training and inference workloads have pushed beyond the limits of monolithic scaling. Traditional GPUs and accelerators face reticle-size ceilings, yield problems, and soaring power and cooling demands. Chiplets solve these constraints by breaking compute into smaller dies—CPUs, GPUs, accelerators, memory, and I/O—then stitching them together with advanced interconnects.

The model is already proven. AMD’s EPYC CPUs and Instinct GPUs rely on chiplet designs. Intel uses Foveros and EMIB (Embedded Multi-die Interconnect Bridge) in its Xeon and GPU hybrids. Nvidia adopted chiplets in its Hopper and Blackwell roadmaps. Hyperscalers like Google, AWS, Microsoft, and Meta are developing modular dies to balance cost, performance, and yield.

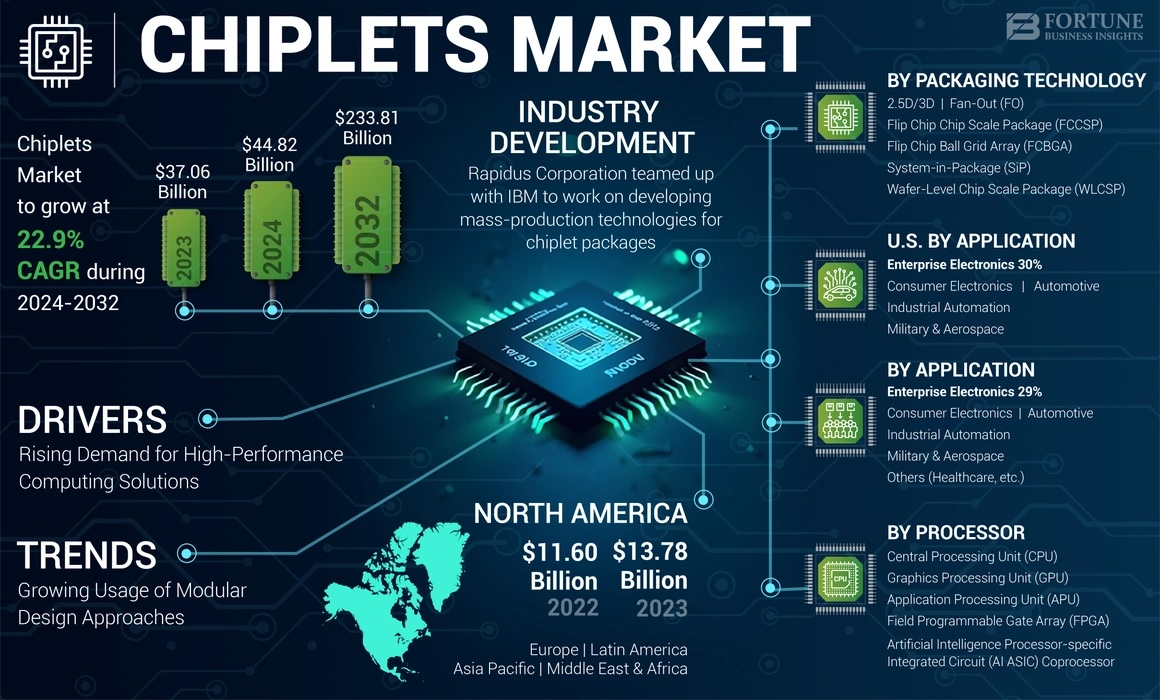

Market forecasts highlight the speed of adoption. Fortune Business Insights valued the global chiplet market at $44.82 billion in 2024 and projects it will reach $233.81 billion by 2032—nearly 23 percent CAGR. The fastest growth is in AI, HPC, and datacenter deployments, where modular compute is shifting from experiment to mainstream infrastructure.

Why GF Bought MIPS

Within this context, GF’s acquisition of MIPS secures direct access to CPU IP tuned for RISC-V. MIPS’ Atlas cores bring multithreading, functional safety, and custom instructions optimized for AI and datacenter workloads. With MIPS under its roof, GF can deliver silicon-proven CPU chiplets already mapped to its 22FDX and 12LP+ FinFET nodes. Customers gain a known-good CPU die—tested, interoperable, and ready for integration.

GF President and COO, Niels Anderskouv stated in recent quarterly report, “MIPS brings a strong heritage of delivering efficient, scalable compute IP tailored for performance-critical applications, which strategically aligns with the evolving demands of AI platforms across diverse markets.”

Automotive adds credibility. While GF has never named Mobileye as the primary driver of the deal, MIPS’ long partnership with Mobileye in ADAS applications underscores its reputation in safety-critical environments. That track record likely factored into GF’s decision.

This clarity of purpose contrasts sharply with Intel. Intel’s CPU business depends on keeping x86 as the anchor die in datacenters, making RISC-V chiplets look like a threat to its core franchise. Intel Foundry Services, however, must sell wafers, packaging, and chiplets to all comers—including RISC-V adopters. Its partnership with SiFive shows the dilemma: enabling RISC-V strengthens Intel’s foundry arm but undermines x86; resisting it protects x86 but limits foundry growth.

The analogy to the earlier “known-good-die” (KGD) era illustrates the stakes. In the 2010s, KGD built the trust system designers needed before investing in costly multi-die packaging. Without it, 2.5D and 3D adoption would have stalled. Today, datacenter chiplets face the same barrier: customers want assurance that CPUs, GPUs, and accelerators will interoperate seamlessly.

GF’s MIPS acquisition positions it to provide exactly that—CPU chiplets validated for AI and HPC. Beyond technology, it also plays into geopolitics. As governments and hyperscalers seek sovereign compute platforms independent of Nvidia and Intel, GF’s ownership of RISC-V CPU IP positions it as a neutral supplier of trusted, open chiplets.

Packaging Power Plays

Owning CPU IP is only the first step. To compete in the chiplet era, GF must also master advanced package integration. This is not unfamiliar ground: after acquiring Chartered Semiconductor in 2010, GF operated an Assembly & Test business in Singapore that offered wirebond, flip-chip, and wafer-level packaging. But as the company refocused on front-end wafer technology, those back-end operations were wound down, leaving GF dependent on OSAT (Outsourced Semiconductor Assembly and Test) partners.

That reliance is problematic because packaging has become the new choke point. TSMC has spent more than a decade perfecting CoWoS (Chip-on-Wafer-on-Substrate), InFO (Integrated Fan-Out), and SoIC (System on Integrated Chips), elevating packaging to a first-class capability. Nvidia’s GPUs, AMD’s server CPUs, and Apple’s processors all depend on these lines. Industry media report that packaging capacity is now one of the primary bottlenecks in global AI chip supply.

Despite rising wafer output, advanced steps such as 2.5D interposers, HBM integration, and 3D stacking are straining available lines. Most of TSMC’s CoWoS capacity is already booked by Nvidia, AMD, and Apple, leaving little room for smaller players. Demand for AI accelerators has outpaced back-end investment, creating long lead times and fierce competition for packaging slots. Packaging has shifted from a back-end process to a strategic resource, as critical to performance and delivery as the fabs themselves.

Intel and Samsung are investing heavily in EMIB, Foveros, and X-Cube, but TSMC remains the entrenched leader with unmatched scale and ecosystem depth. For GF, the MIPS acquisition provides the anchor CPU chiplets, but without building in-house packaging capacity—or forging deeper ties with leading OSATs such as ASE, Amkor, and JCET—it risks being shut out of the highest-value datacenter opportunities. These partners bring expertise in 2.5D/3D integration, fan-out wafer-level packaging, and automotive-grade reliability—areas where GF still trails.

Foundries, OSATs, and Marketplace Models

Intel promotes EMIB and Foveros but still leans on OSATs. Samsung offers I-Cube and X-Cube with heavier OSAT reliance. GF, by contrast, does not yet operate advanced packaging at this scale and relies primarily on partnerships. Meanwhile, TSMC is building a neutral chiplet marketplace, with partners such as SiFive, Andes, and Arm supplying CPU IP. For each, TSMC maintains the GDSII layouts, test data, and packaging rules.

Chiplets are then fabricated, validated, and packaged on demand. This model positions TSMC as an impartial enabler, offering interoperable building blocks that customers can combine with memory, accelerators, or custom logic. Unlike Arm’s original design-time macros, TSMC delivers finished dies, ready for integration.

GF is pursuing a hybrid path: it owns CPU IP through MIPS to offer anchor dies but must rely on OSAT partnerships for packaging. Samsung leverages its memory dominance, Rapidus emphasizes sovereignty through Renesas, and Intel struggles with neutrality because of x86.

Physical AI and the Sovereignty Play

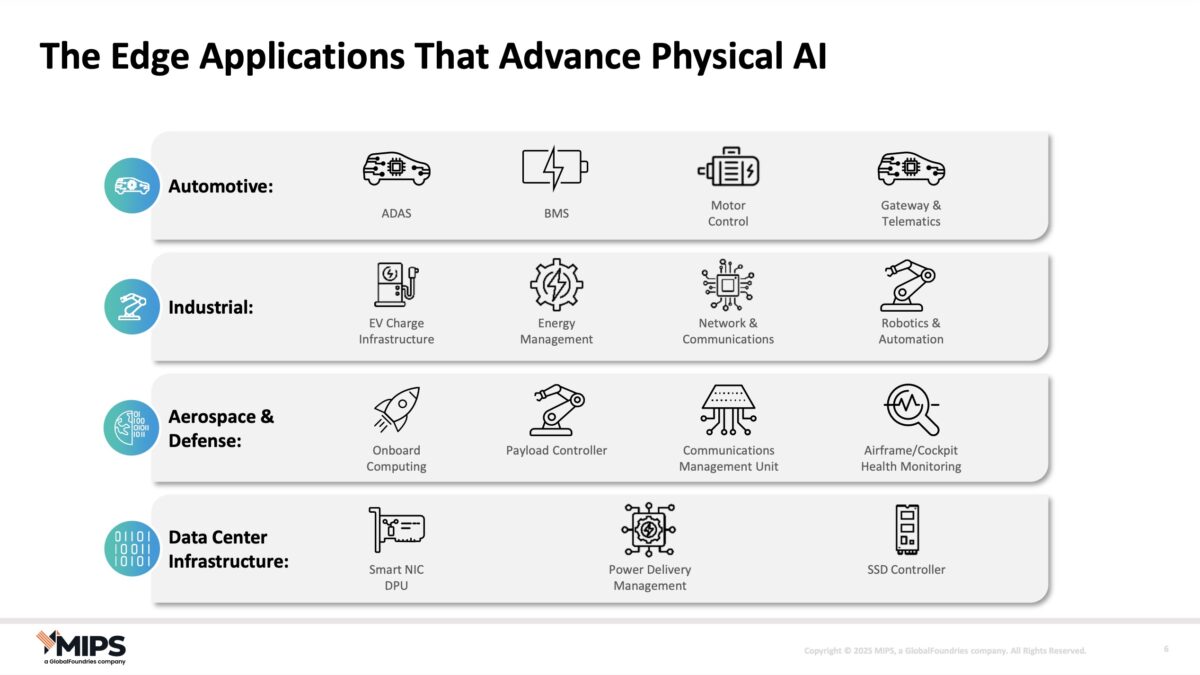

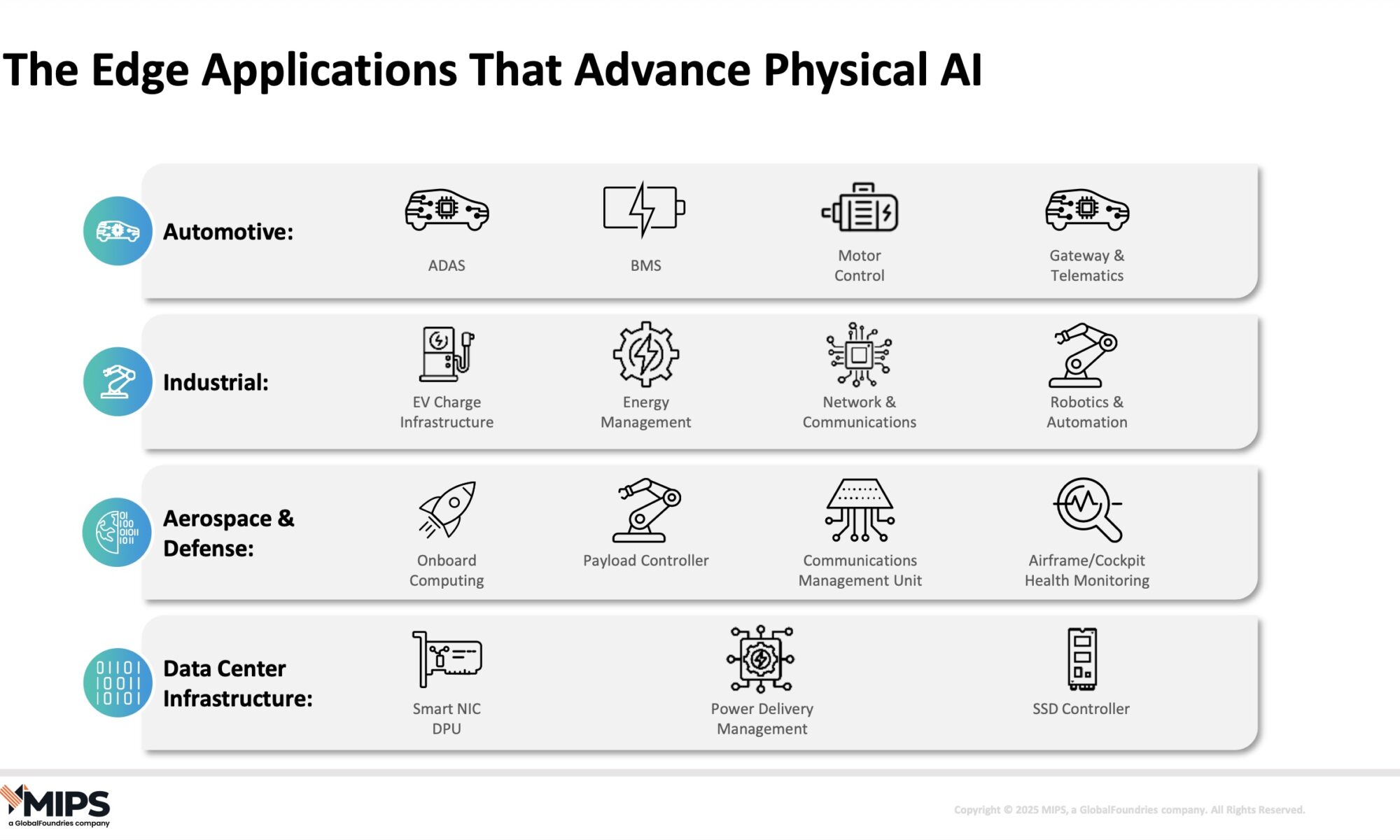

GF frames the MIPS acquisition as enabling “Physical AI”—processors that not only sense and infer but act in real time for robotics, autonomous driving, and Smart NIC DPU. But the immediate battleground is datacenter AI. With chiplets becoming the architecture of choice, GF is positioning itself not just as a wafer supplier but as a strategic partner, offering anchor dies for sovereign compute platforms.

In practice, GF’s strongest near-term opportunities lie in automotive and edge AI, where its process nodes align with safety, reliability, and low-power requirements. Its datacenter ambitions may depend less on competing head-to-head with TSMC and more on offering sovereign, open alternatives through chiplets. In the race to define the backbone of AI datacenters, GF’s MIPS bet is less about reviving a legacy brand and more about ensuring relevance in a modular, sovereign compute era.

Also Read:

Breaking the Thermal Wall: TSMC Demonstrates Direct-to-Silicon Liquid Cooling on CoWoS®

Sofics’ ESD Innovations Power AI and Radiation-Hardened Breakthroughs on TSMC Platforms

Share this post via:

The Name Changes but the Vision Remains the Same – ESD Alliance Through the Years