COVID-19 underscores the importance of US-based production for strategic industries

COVID-19 underscores the importance of US-based production for strategic industries

The COVID-19 pandemic has drawn intense focus on the need to repatriate pharmaceutical manufacturing back to the United States. The increased awareness that a strategic adversary manufactures or controls up to 80% of the active pharmaceutical ingredients used to produce drugs has shocked the nation’s sensibility. What other strategic industries are at risk of offshore dependency? Foremost on the list is electronics, most especially the semiconductor industry.

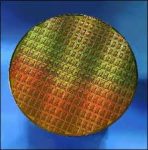

No industry has a more pervasive and strategic impact on the economy than semiconductors. “Chips” are the essential infrastructure of the digital economy, embedded in every connected hardware platform. They drive consumer electronics, telecommunications, media, the internet, the cloud, transport, medical discovery and medical devices, education, finance, energy, agriculture, government and more. US national security runs on chips, including defense, intelligence, cyber and space. To safeguard the digital economy during conflict or national crisis, the US Government must take a more proactive posture to guard against offshore dependency and supply disruption.

The semiconductor industry is a complex global network of companies including product design, design tools and intellectual property (IP), chip manufacturing, outsourced packaging and test (OSAT) and semiconductor equipment and materials. “Fabless” firms solely design chips. “Foundries” focus exclusively on manufacturing. The “Integrated Device Manufacturers” (IDMs) both design and manufacture chips. The US has capable manufacturers in Intel, TI, On Semiconductor and Micron, but as IDMs they only manufacture products they design. With the benefit of their decades-long investments in the United States, for the products that they make, the US is well prepared.

However, for many other high-volume chips used across essential digital platforms, the US is critically dependent on offshore factories. This is evident in the supply of leading-edge technologies and the equipment and materials central to the manufacturing process. Fabless product companies such as Qualcomm, AMD and Xilinx have virtually all leading-edge products (7 nanometer and below) manufactured offshore, mostly at TSMC in Taiwan. The commercial Foundries in the US, GLOBALFOUNDRIES and TowerJazz, do not offer leading edge technology. AMKOR, the only US-based commercial-scale OSAT, has all its manufacturing located offshore. Dutch equipment company ASML holds a virtual monopoly on lithography equipment, arguably the most critical step in chip production. Key rare earth raw materials such as cobalt, gallium, tungsten and germanium are critical to chip production. China is estimated to hold at least 80% of world production of these and other rare earth materials.

A prolonged denial of access to suppliers in Taiwan, South Korea, Japan and elsewhere in Southeast Asia during time of crisis would severely risk supply of chips for US communications networks, data centers, medical devices, financial systems and the electric grid. While the US has effective mitigation to assure the supply of critical parts for national security through the Department of Defense’s Trusted Foundry, its scope and scale are insufficient to address our nation’s other critical infrastructure needs. United States policy should target self-sufficiency for both national security and critical infrastructure needs.

Domestic “burst” capacity in chip manufacturing is a much tougher task than production of ventilators, masks and personal protective equipment – as important as these are to our current national emergency. The issue is time. To build, equip, qualify and ramp a new chip factory requires minimally up to two years, time well beyond that needed to meet an emergency. Existing factories at Intel, GLOBALFOUNDRIES, TI, On Semiconductor and Micron could be re-purposed on a quicker timetable, but these companies would need access to the IP and know-how of offshore competitors such as TSMC, and potentially additional equipment, to build non-IDM and leading edge products. Alternately, Fabless firms could re-spin their product designs to be built on US-based IDM process technologies, a non-trivial effort requiring several months to achieve volume. Invoking the Defense Production Act can trigger action but not solve the issue of time.

Decisive US policy is needed to re-balance the equation between government-led readiness and the continuation of an un-bridled free market approach to semiconductor manufacturing.

First, the Administration needs to adopt policy proposals that enhance, not diminish, the competitiveness of our leading semiconductor companies. For example, the pending decision to invoke the “foreign direct product rule” to inhibit supply of chips to Huawei will inflict severe financial damage to US equipment suppliers and hand hard-earned market share to Japan and South Korea. Next, US should fund aggressive financial incentives for both US and global manufacturers (with focus on TSMC and Samsung) to build or expand leading-edge factories in the US. This plan should include subsidies for capital and operating expenditures sufficient to eliminate current cost disadvantages versus Southeast Asia as well as competitive tax incentives. Creative public-private models can achieve the best of the innovative and efficient private sector while assuring adequate, responsive US-based supply. Third, US should fund a Strategic Semiconductor Reserve comprised of US Government priority access to domestic “burst” manufacturing capacity, physical stockpiles of rare earth materials, and in concert with industry, a government-funded virtual finished goods inventory of chips and other components found in essential infrastructure platforms. Finally, the US should expand advanced research funding to assure US leadership in Artificial Intelligence, 5G, quantum computing and other emerging technologies.

Whether in a Phase 4 “infrastructure” bill or a normal appropriation cycle, The President and Congress must think expansively in redressing the strategic risk inherent in the current US posture. One prefers that a free trade regime govern independent investment decisions by US and global corporations. But as COVID-19 has brought to light, establishing national readiness for exceptional circumstances requires implementation of pro-active public policy ahead of crisis.

Terry Daly is a retired semiconductor industry executive

Share this post via:

A Century of Miracles: From the FET’s Inception to the Horizons Ahead