A strange narrative took hold in the U.S. at the end of 2020 that vehicle sales were in decline, that cars weren’t selling. The reality is something quite different. In spite of nearly two solid months of auto factory and dealership shutdowns, automotive sales surged back in 2020 – a phenomenon that manifested globally with regional variation.

It took a Herculean effort on the part of auto makers accommodating auto workers and new car dealers accommodating uneasy customers, but the industry facilitated a miraculous recovery. For most makers and dealers sales are percolating again. In fact, several car makers selling cars in North America ran short of larger vehicles such as SUVs, crossovers, and pickup trucks. Turns out, cars and light trucks are pretty essential for a lot of people.

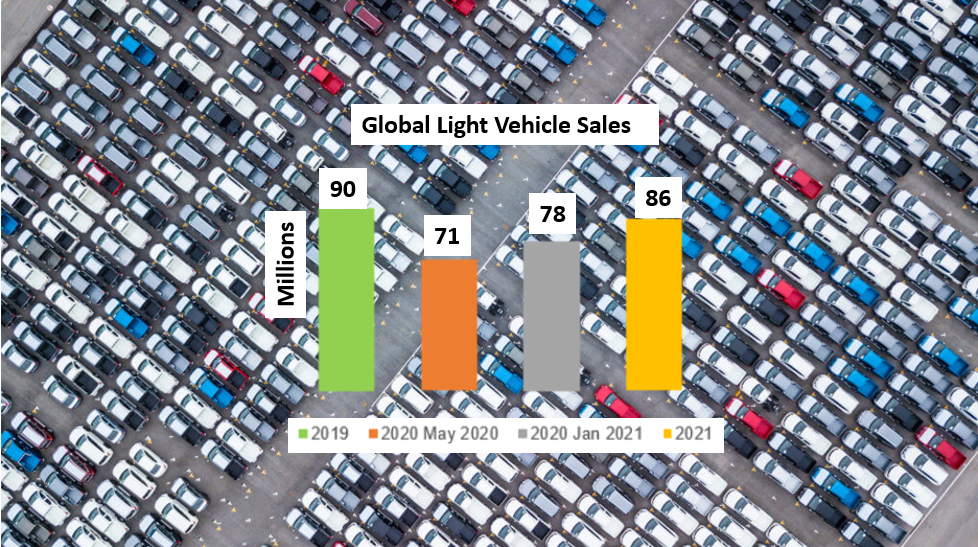

If the COVID-19 pandemic were negatively impacting vehicle sales in a prolonged and predictable way I might agree with the gloom and doomers. In fact, forecaster LMC Automotive estimates the negative impact of the two-month COVID vehicle/production sales hiatus (in the U.S. and elsewhere around the globe) to be a 15.8% hit to 2019 production volumes – to 74.1M vehicles produced globally, down from 89M in 2019.

LMC expects a recovery to pre-COVID production volumes by 2022 with steady growth eventually pushing volume toward and beyond 100M units annually. So it looks like cars are going to be with us for a while.

The fact is that the onset of COVID-19 has scrambled the anti-car culture dialectic that society, as a whole, was steadily evolving toward a carless future. This week kicked off with a story in USA Today (sourced from LawnStarter.com) describing the 10 best cities to live without a car. This is not to be confused with Curbed’s report on the 14 best car-free cities.

The vision of carlessness was gathering steam prior to the arrival of COVID-19. We saw the rise of congestion charging in London and Stockholm, to discourage the introduction of vehicles from the suburbs into city centers. We also saw bans on diesel fueled vehicles in multiple German cities battling smog. And we saw cities such as Paris and New York introduce roadway “diets” to reduce the available travel lanes for cars in favor of pedestrians, bikes, and scooters.

Further, we saw multiple countries – primarily but not only in Europe – pronounce end dates for the sale of internal combustion-based vehicles within 10 or 15 years. But flying in the face of these sanctions on individual vehicle ownership and operation, COVID-19 has directly and negatively impacted demand for mass transit – due to lockdowns and rider reluctance.

Consumers are increasingly opting for cars in a manner that is disrupting what was once a subtle and orderly transition away from cars. In the pre-COVID times cities were discouraging the creation of additional parking with new apartment and office construction. Clever policy makers were shifting the emphasis away from requiring sufficient parking in favor of a focus on public or ad hoc transportation options.

Now comes the report – also this week – from The New York Times that growing individual car ownership is making it increasingly difficult to find parking in New York’s residential neighborhoods. What this story misses is the reality that COVID-19’s impact is more complex than simply stimulating demand for individually owned and operated vehicles as consumers turn away from declining mass transit options.

The New York Times is right, though, to zero in on parking as the key pain point in shifting consumer transportation preferences. Indeed, parking is at the heart of the private car ownership “crisis” – if I may call it that. While the still fledgling transition to electric vehicles has introduced range anxiety, parking anxiety has always been and always will be a controlling factor for individually owned and operated vehicles.

Hans-Hendrik Puvogel, chief operating officer for Parkopedia, notes that the impact on parking is not really the old (and incorrect) 30% of traffic results from drivers driving around seeking parking spaces, but rather a shift in terms of usage patterns of parking assets.

“Residential parking is much more in demand than before. Street parking is in process of getting re-purposed for pickup/drop-off points, bike lanes, and loading zones. So, other off-street assets become very interesting (hotel and office parking and long-term parking in commercial parking garages).

“On the other hand, transient parking needs will decrease, as people stay at home, work from home, shop from home. In the short term that is going to create a mess in terms of parking and traffic, as the parking infrastructure is still geared for the old pre-Covid times, but eventually we will see a transformation of parking in the city centers.”

In response to this new reality, some expect shared robotaxis to replace privately owned vehicles. Don’t count on it. Sunny cities like Phoenix or tech hubs like San Francisco – will become increasingly overrun with robotaxis and will be forced to turn to road use tolling as in Singapore, Puvogel says.

Brutal economics will determine whether already deeply indebted robotaxi operators will be able to maintain fleets of driverless vehicles in constant motion when not charging. Cities are likely to have a low tolerance for these operators further tying up already clogged streets.

The policy implications for the car removers, with their road diets and reduced parking requirements for new construction, will be a forced rethink. Ample public parking and charging (for EVs) will be necessary to accommodate the growing flock of privately owned vehicles during a prolonged period of COVID-19 recovery during which mass transit will need to build back operations and rider confidence.

In the meantime, parking anxiety will become increasingly pronounced and companies, like Parkopedia, with solutions for locating the closest and cheapest parking spaces will thrive. The Car Wars of 2021 will be a battle for open parking spaces and available and compatible EV charging locations. Car-less living will simply have to wait for another decade or two.

Memory Matters: Signals from the 2025 NVM Survey