Uber has taken a highly profitable business and turned it into a very unprofitable and dangerous one with the help of the pandemic. With guile, innovation, and theft, Uber founder and pitchman, Travis Kalanick, spun up the ride hailing wonder into a global transportation leader built upon rapid growth and a bare knuckle approach to competitors and regulators.

The freewheeling ways of Kalanick caught up with him and he was replaced by the more sedate, though no less clever, Dara Khosrowshahi. With fast growth in the rearview mirror at Uber, Khosrowshahi has been forced to turn to distraction and misdirection to simultaneously satisfy drivers, regulators, and investors.

Uber investor presentation: https://s23.q4cdn.com/407969754/files/doc_financials/2020/q2/InvestorPresentation_2020_Q2.pdf

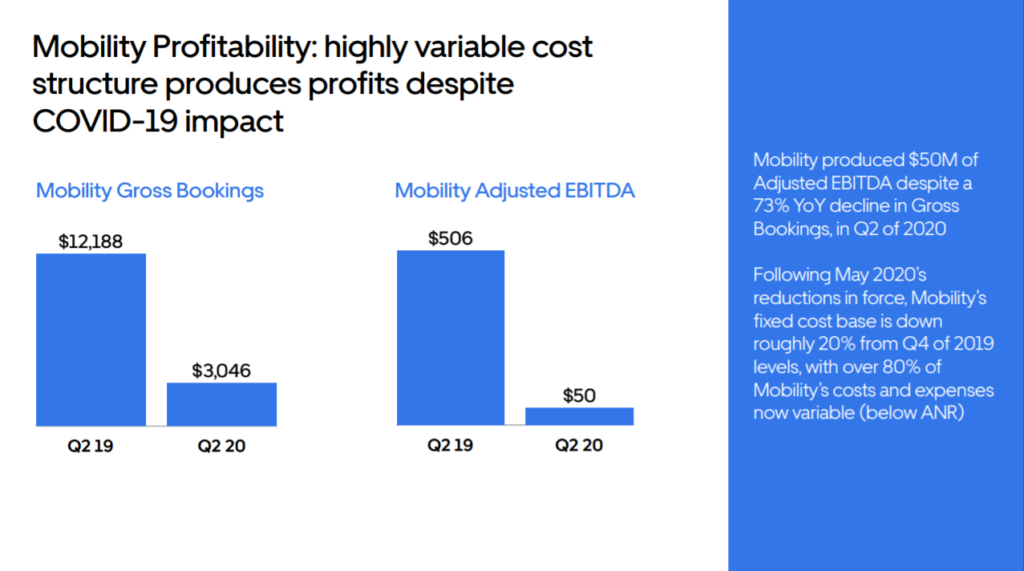

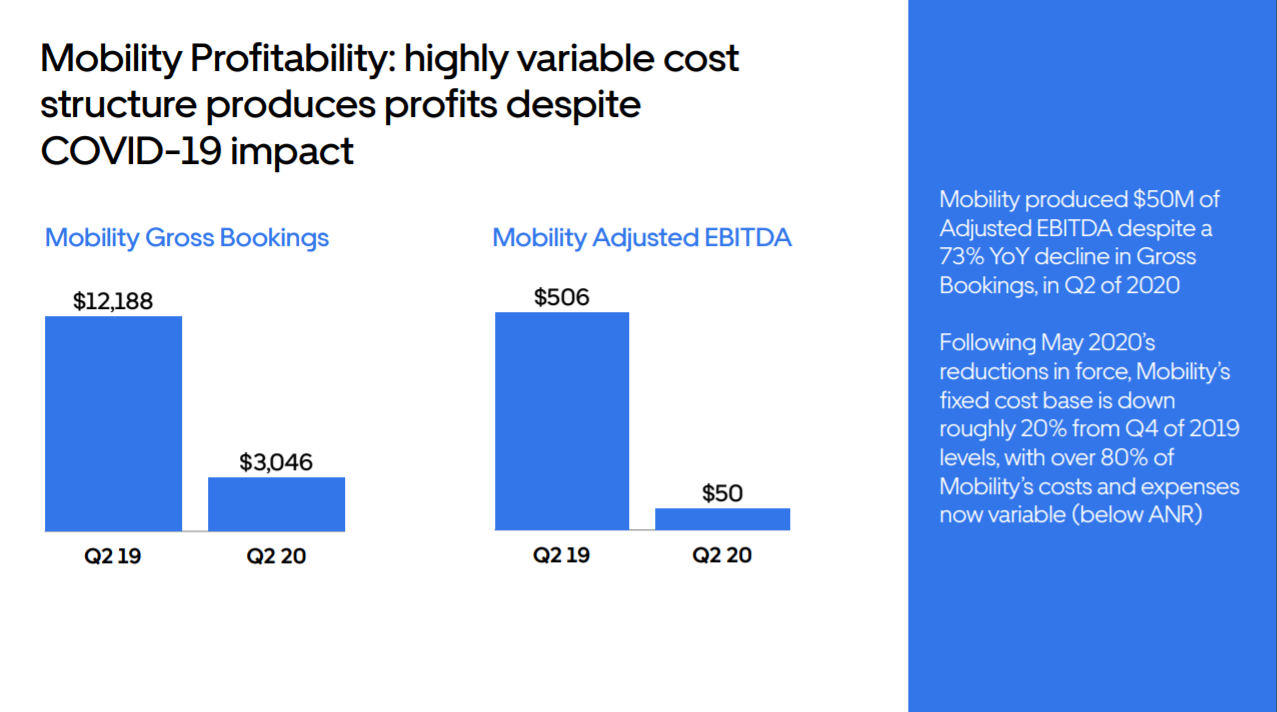

This post-pandemic chapter of Uber’s existence has seen the company’s business model whipsawed – simultaneously validated and vanquished – as drivers and their cars vanished along with demand for ride hailing services. The ride hailing business plunged 70%-80% around the world suddenly thrusting Uber into the uncomfortable position of no longer being able to deliver relentless growth.

To compensate, Uber embraced food delivery doubling down on its up and coming Uber Eats operation and acquiring rival Postmates. The move allowed Uber to perform an impressive pirouette shifting its business mix nearly overnight from majority people delivery to majority food delivery.

Khosrowshahi put on a distracting show for investors last week with a 57-slide presentation touting the merits of food delivery for restoring rapid growth to Uber’s prospective revenue even as the company enters a second highly competitive space. The key difference, though, between food delivery and people delivery is the uncertain prospect for profits.

Not only are margins tighter – if they exist at all – in food delivery, competition in the sector globally is already intense. There is no question that a pivot to food delivery made sense and makes sense in the context of rolling economic lockdowns around the world in the face of the coronavirus pandemic, but the associated profit margins remain unproven.

Investors clearly bought Khoshrowshahi’s pitch as Uber’s stock survived last week’s earnings report fairly unscathed. But Khoshrowshahi followed up that pitch with an opinion piece in the New York Times this week simultaneously arguing for and against treating its drivers as employees by offering them benefits.

Khosrowshahi’s NYTimes commentary speaks to the fallacy underlying Uber’s business model. Uber famously doesn’t own any cars and uses drivers that are not employees. This is the key to Uber’s – and other ride hailing operator’s – profitability – limited capital investment and limited obligations to drivers.

The model was validated during lockdown because drivers vanished at the same time as passengers thereby immediately reducing expenses – though also destroying revenue. The pandemic arrived in the midst of Uber’s regulatory battles with the U.S. states of New York and California, both of which have been seeking to force the company to treat its drivers as employees. (Something similar is playing out, still, in London, as well.)

But freedom and flexibility are the foundations of Uber. Khosrowshahi argues in the New York Times that it offers its gig workers that which they value most highly: maximum flexibility. If the company were to treat its drivers as employees they not only would lose that flexibility, but Uber wouldn’t be able to employ as many of them. And without that famous flexibility, it would be more difficult to recruit drivers.

If Uber offers any benefits at all to its contractor drivers, writes Khosrowshahi, they legally become, in many if not most states, employees with a range of legal obligations that undermine the otherwise highly profitable business model. Khosrowshahi argues for the creation of a third path forward whereby the company could offer gig workers some benefits, such as a contribution to pay for healthcare, without triggering full employment obligations and regulations.

In the end, Khosrowshahi’s “third way” – as he describes it – crafted in response to a critical editorial published by the New York Times – is yet another distraction. Khosrowshahi says that if such a system had been in place the company would have contributed $665M toward driver benefits last year alone.

The argument is a distraction because Khosrowshahi maintains that most drivers don’t want these benefits. Most already have healthcare coverage from other sources and they want to preserve their flexibility.

Dara Khosrowshahi’s distractions mask a bigger fundamental problem for Uber and other ride hailing operators that function in a similar manner. The company is founded on maximum freedom and flexibility and minimum accountability and reliability.

It is only recently that Uber has begun advertising its service to consumers. Previously, Uber almost exclusively advertised in order to recruit drivers. There is a reason for this. Uber cannot deliver a reliable and predictable level of service because of its maximum freedom and flexibility ethos.

There are no protocols around how passengers are treated. In fact, Uber passengers and drivers both routinely report abusive interactions. Uber’s freewheeling approach has ultimately undermined its ability to commit to any quality of service commitment.

In a post-coronavirus world, this max-flex strategy means drivers and passengers are supposed to wear masks – but do not always do so. Worse, Uber has failed to require drivers to install partitions between the front seat and passenger compartments of their cars.

There’s a reason Uber’s ride hailing revenue remains well below pre-COVID-19 levels. It is simply unsafe to hail and ride in an Uber without driver and passenger-protecting partitions. Uber may require masks, but masks are insufficient for safe delivery of people in the confined space of an automobile.

The truly strange thing about Uber, though, is the willingness and ability of the company to throw around big figures like $665M for driver benefits or $8B in the bank without defining a pro-active strategy for making driving safer and treating drivers better. Clearly Uber has the resources to do the right thing. Instead, CEO Khosrowshahi is punting the ball to regulators to find a “third way” solution to the company’s contractor-employee conundrum.

Khosrowshahi’s distractions and disingenuousness are unsafe at any speed. Food delivery will not deliver enough growth or profit to save Uber. The company must fix its fundamentals or, in the long run, it will fail.

New York Times – “I am the CEO of Uber. Gig Workers Deserve Better” – https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/10/opinion/uber-ceo-dara-khosrowshahi-gig-workers-deserve-better.html

Rideshareguy Interview with Dara Khosrowshahi: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rSiNJCwbcEk

Share this post via:

A Century of Miracles: From the FET’s Inception to the Horizons Ahead