There’s more than one way to build a quantum computer (QC) though it took me a while to find a good reference. I finally settled on Building Quantum Computers: A Practical Introduction. Excellent book but designed only for those who will enjoy lots of quantum math. I’m going to spare you that and instead describe a couple of the more popular technologies and the challenges they face. My summary of challenges here is highly selective in the interest of a quick read.

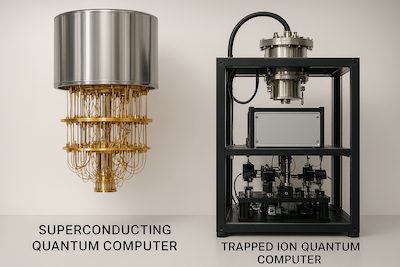

Superconducting QC

I touched on this topic a little in an earlier blog so I’ll add some new info here. Superconductivity emerges below relatively modest temperatures, >4 kelvin, but QCs are cooled to tens of millikelvin to reduce thermal noise. The volume a dilution fridge can economically drop to this temperature is quite small, not an issue for the chip but a big issue for control wiring/microwave guides. This can limit scaling qubit counts since qubit operations and readout are controlled by these signals.

Programming control depends on microwave resonances with qubits. Each qubit can be tuned in-situ to have a unique resonant frequency but put enough qubits near each other plus tuned microwave stimulus with finite frequency spread and it is easy for stimulus to stray beyond the intended target, triggering other qubits.

Physical constraints on-chip are challenging. Connecting an array of qubits is easiest through a grid of rather bulky waveguides but such topologies are significantly limiting for programmability options if only nearest neighbors can interact. As another way to increase densities, 3D stacking is an active area of research. IBM is already showing stacking in their Eagle processor family, qubits in one layer, resonators in a layer below that, allowing for higher densities. (Interestingly Eagle doesn’t aim for highest possible qubit densities, instead favoring reduced error rates.) IBM currently holds the record for (noisy) qubits on a chip on their Condor series at 1,121, though they don’t advertise area.

These technologies have quite short coherence times (~microseconds to milliseconds, the time before any carefully constructed quantum state collapses), though gate speeds are ~1000 times faster than in trapped ion technologies.

Trapped ion QC

Transitions between key energy levels in ions provide highly accurate time references. These have a long history (1950s) and are foundational in atomic time standards used in e.g. GPS support. Application to quantum computing was an obvious extension and first appeared around the mid 1990s, a little earlier than superconducting quantum computing.

The basic idea is simple. An ion with a single electron outside otherwise closed shells (e.g. Ca+) will exhibit energy levels roughly comparable to hydrogen, the simplest and most comprehensively understood atom in quantum theory and therefore an excellent basis for a qubit. A string of such ions can be captured in an ion “trap”, held in place by a combination of static and oscillating electric/magnetic fields. Contemporary traps are built using familiar microfabrication techniques, embedding control electrodes in a planar surface and floating the ions about 100um above the surface.

Qubit states are controlled by lasers or magnetic fields and are read by lasers, in either case structurally simpler than the waveguides so far exhibited in superconducting technologies. A single qubit gate is implemented by a pulse targeting an individual (localized) ion to excite transitions between ground and first excited states (|0> and |1> states in qubit terms). 2-qubit gates use 2 phase-coherent laser beams and additional quantized motional degrees of freedom in this technology to entangle two qubits (I don’t know the method for magnetic control).

There is a limit to how many ions can be held effectively in a single trap (tens of ions from what I have seen though records stretch to a few hundred), so scaling is accomplished by replicating traps and coupling them through photon exchange between traps. Highest counts I have seen (Quantinuum) are 56 qubits. Reported area for a chip is “thumbnail size”. IonQ is another trapped ion player, claiming a more scalable architecture, whereas Quantinuum claims superior accuracy and performance.

Trapped ion systems still use ultra-low cooling infrastructure (though they do not depend on superconductivity) and a vacuum chamber. Replicating this machinery many times would be expensive and likely would suffer reliability problems. On metrics, trapped ion technologies are ahead significantly in coherence times (up to seconds or even hours) and fidelity/accuracy of gate operations, which might (?) suggest less complex quantum error correction machinery. However, trapped ion system gate speeds are quite a bit slower than other technologies.

Quantum error correction

This topic could be differentiating between competing solutions. Here’s my take based on what I can find on IBM and Quantinuum in this area.

A common approach to address QEC is by entangling multiple physical qubits for a logical qubit. This had required 1000:1 physical to logical qubits in superconducting systems which IBM now admits was impractical. They recently published (see the link) a new method which reduces this requirement considerably. This method they claim should make a large-scale fault-tolerant quantum computer practical by 2029. The target system at that point, Starling, should feature 200 logical qubits and be capable of performing 100 million quantum operations.

Quantinuum with Microsoft have demonstrated an even lower required physical to logical qubit ratio in their ion-based system and anticipate that their target Apollo system in 2029 will support 100s of logical qubits with very low error rates. Interesting that IBM and Quantinuum carefully avoid side-by-side comparisons except on logical qubit counts 😀.

Takeaways

These technologies continue to advance though neither has yet reached production level based on their projections. However they have both pulled in their target date by a year, to 2029. There are some commonalities with semiconductor fabrication but how big an overlap remains to be seen. Still an interesting area to watch. Who knows what new breakthroughs will emerge in that window?

By the way, shout-out to Fred Chen for prodding me to go deeper in this area 😀

Share this post via:

Advancing Automotive Memory: Development of an 8nm 128Mb Embedded STT-MRAM with Sub-ppm Reliability