Dassault have recently been granted a patent on their approach to managing design hierarchy. I asked them how long it took from filing the patent until it was granted and they said the whole process had taken 8 years. It is a bit of an indictment of the patent system when it takes 8 years, also known as 4 or 5 process nodes, for a patent to issue in an industry as fast-moving as semiconductor design. Even in Dassault’s slower moving main business of mechanical design, 8 years is a long time. That’s longer than the 787 took to create from when Boeing decided to start until delivery started a couple of years ago. In electronics, it is so far back that it predates the iPhone, which launched the smartphone era and the transition from PCs to mobile.

Dassault have recently been granted a patent on their approach to managing design hierarchy. I asked them how long it took from filing the patent until it was granted and they said the whole process had taken 8 years. It is a bit of an indictment of the patent system when it takes 8 years, also known as 4 or 5 process nodes, for a patent to issue in an industry as fast-moving as semiconductor design. Even in Dassault’s slower moving main business of mechanical design, 8 years is a long time. That’s longer than the 787 took to create from when Boeing decided to start until delivery started a couple of years ago. In electronics, it is so far back that it predates the iPhone, which launched the smartphone era and the transition from PCs to mobile.

The patent is 8,521,736. As with all patents it is pretty unreadable. There are only so many times you can read about a “pluraiity of modules” or “a machine-readable storage device” (aka a file) before your eyes glaze over. Despite the official rationale that a patent is a limited monopoly in return for disclosing how to do whatever it is, I’ve never come across anyone in the software world who has used a patent as a basis for implementation. In fact lawyers at companies where I’ve worked have told us not to look at patents so we can’t accidentally be accused of “willful” infringement which caries punitive damages.

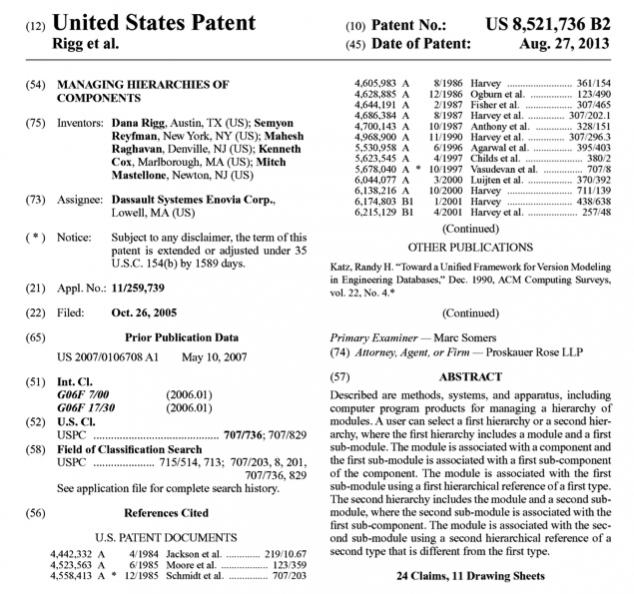

So what is Dassault’s patent all about? Static and dynamic selectors are maintained on each module version that has a hierarchical reference to another module. Static selectors are fixed as each module is checked in, but dynamic selectors point to the latest version unless specifically tagged. So the static selectors give a consistent view of the entire design as checked in, but the dynamic view allows the latest versions of everything to be examined (or manually can pick a mixture of different modules at different stages).

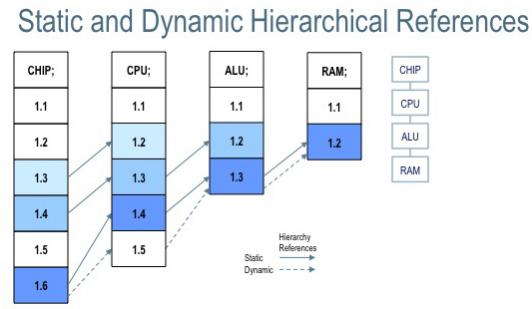

Since modules can be tagged arbitrarily, it is possible to use the dynamic configuration to pick up specific key stable vesions such as “GOLD” or “TAPEOUT”. The means it is possible to control easily whether to have a fully static design, fully dynamic or, usually, some sort of mixture.

In a small example, this capability doesn’t seem all that useful, but when configuring modern SoC designs that may contain literally millions of files developed with geographically dispersed teams. Tags can be used to specify design locations, particular IP (e.g. blocks in an ARM microprocessor), phases of the design, or anything else that will turn out to be useful when trying to pull a particular configuration together (all the latest stuff in San Jose with the stable version from Bangalore, for example).

This capability is used within DesignSync for electronic design. Although mechanical design also uses hierarchy, it is much simpler than electronics because a lot is just a black-box that cannot be pushed down into, unlike with a chip design where ultimately everything is a polygon on a mask or it doesn’t exist. Designing a plane you can’t just push into the engine internals.

More articles by Paul McLellan…

Share this post via:

CEO Interview with Jerome Paye of TAU Systems