Fisita World Mobility Summit 2019 in Nagoya, Japan, brought together powerful perspectives on everything from vehicle architectures (Visteon), to open source software (Synopsys), mobility (METI), and connectivity (Bosch). The most enigmatic juxtaposition at the event, however, came in a panel discussion I moderated between General Motors’ Vice President, Global Electrification, Controls, Software and Electronic Hardware, Dan Nicholson, and Dr. Kazunari Sasaki, professor (hydrogen energy systems) and senior vice president, Kyushu University.

These two executives stand at the fulcrum of vehicle propulsion facing tectonic forces tearing at the automotive industry. For Professor Sasaki, residing as he does in the energy desert of Japan, hydrogen is the future – promising a clean, energy independent path to future mobility.

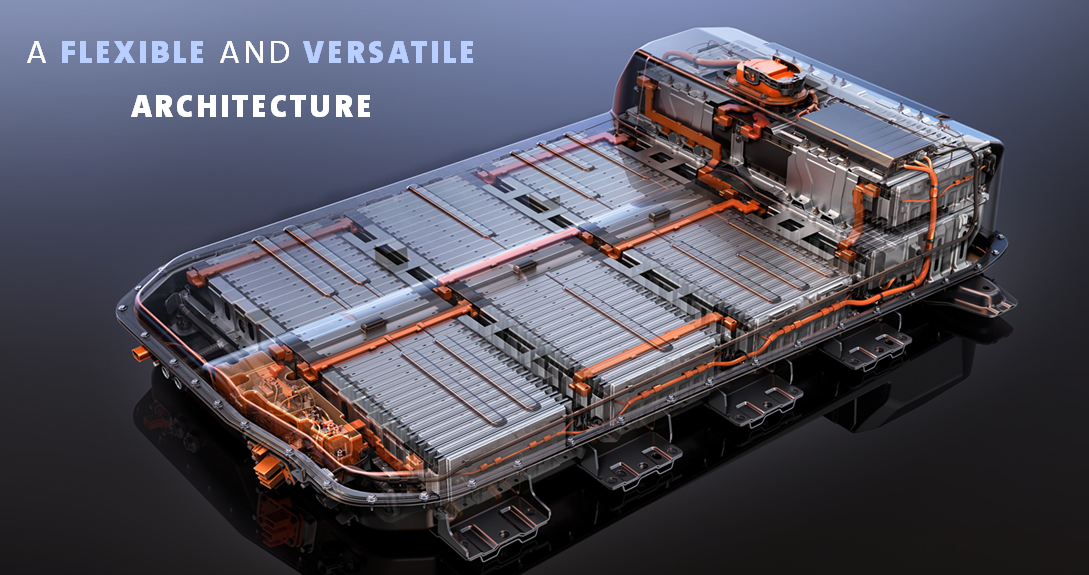

For Mr. Nicholson of GM, all roads lead away from proven profitable propulsion technologies such as diesel and internal combustion engines. The third slide Nicholson showed in his presentation was of a diesel-powered, extended-cab Chevrolet pick-up truck towing a massive trailer. His fifth slide was an artist’s rendering of GM’s new global electric vehicle platform.

The existential crisis posed by these two perspectives is hard to ignore. For Sasaki, the choice of hydrogen is clear, clean, and rational if not downright essential. As noted by a Toyota Advanced Development (AD) executive, James Kuffner, in the closing presentation of the Fisita event: “Hydrogen has an energy density that is 3x higher than gasoline and an overall higher maximum efficiency. If you combine a hydrogen fuel cell with an electric motor, the efficiency is 2x or 3x more efficient than a conventional gas engine.”

Sasaki was also quick to note that hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe and that the primary byproduct of the hydrogen energy cycle is water vapor. When put this way, opponents of hydrogen would appear to be either ignorant or foolish – or “fuelish” to borrow Tesla Motors’ CEO Elon Musk’s disparaging assessment of hydrogen’s prospects.

For Nicholson, GM is in the midst of a massive corporate pivot away from smaller passenger cars toward crossovers and SUVs, away from internal combustion engines to electric powertrains, and away from human-centric driving to autonomy. This is Clayton Christensen’s “creative destruction” on steroids threatening 40% of the legacy ICE supply chain and a good portion of the vehicle assembly workforce – painful for GM having just recently concluded a month-long UAW strike.

Unfortunately for Nicholson the Fisita event occurred prior to GM’s latest earnings report and before the company announced plans for a new EV battery assembly plant (a joint venture with LG Chem) in Lordstown along with its intentions to build an EV pickup truck in Hamtramck by 2021. As a result, Nicholson was noncommittal as to the timing of GM’s wider deployment of EV technology.

What is clear, though, is that the shift to EV technology, by Nicholson’s own description, has significant implications for the role of software and connectivity in future electrified vehicles. These implications are touching the entire architectural underpinnings of the vehicle – which was reflected in the domain consolidation strategy described by Markus Schupfner, senior vice president and chief technology officer for Visteon speaking at the Fisita Summit.

As bleak (and promising) as the picture may be for a legacy ICE-oriented manufacturer like GM, the prospects for the promoters of hydrogen are more grim and hold important lessons for auto makers. The merits of hydrogen propulsion are both indisputable and debatable – and they are likely to be debated until that massive ball of hydrogen and helium in the sky implodes.

The automotive poster child for hydrogen propulsion is Toyota’s Mirai. This vehicle offers an important example of both the lengths and limits to which an automobile company can stretch to promote a vehicle it desperately wants to be successful – in the face of massive consumer indifference.

After four years, Toyota claims to have put 6,000 hydrogen-powered Mirai’s on the road in the U.S. These have been hard won sales with a range of consumer incentives including:

· A complimentary fuel cell card worth $15,000

· $2,500 in loyalty cash

· $7,500 in bonus cash

· 1.9% financing for 72 months

The incentives are necessary given the limits of the current network of fueling stations confined mainly to California. The limits of existing fueling options and the weakness of the current hydrogen infrastructure was made clear when a catastrophic fire and explosion occurred at an Air Products hydrogen plant in Santa Ana, California, in June of this year knocking out hydrogen supplies for Northern California for five months.

The Air Products disaster forced owners of hydrogen-fueled vehicles to idle or trade them in. (The high cost of luxury car insurance was noted by some as a reason for turning their cars in. Toyota representatives said the company took on the lease or financing payments for some Mirai owners.)

The developments in California could and should be seen by many as the end of the hydrogen car conversation in the U.S. Hydrogen may make sense for commercial vehicles and public transportation, but the vulnerability of an already fragile and fledgling charging network is likely to be too much for even the greenest of green-leaning car buyers to tolerate. There are two valuable takeaways here.

First, California, like Japan, has geographic and geologic reasons for taking a regulatory interest in the automotive market. Both Japan and California are concerned about emissions. But Japan has an abiding interest in energy independence and California has a perpetual struggle with air quality.

These circumstances of geography give both regions common cause to promote both electrification and hydrogen fuel technologies. California has been willing to put its thumb on the scale for electrification with stringent emissions and fuel efficiency standards – but neither Japan nor California have provided incentives for hydrogen-fueled vehicles.

This has put companies like Toyota, Hyundai, and Honda in the awkward position of advertising, promoting, and selling hydrogen-powered cars that may be green but are complicated and expensive to operate from a cost, charging, and insurance standpoint. The array of incentives offered by Toyota on the Mirai represent a case study in how a car company tries to sell a car against the headwinds of consumer indifference.

It is instructional to compare the enthusiastic funding of charging and the range of discounts and discounted financing Toyota is offering for the Mirai against the lack of aggressive promotional activity by BMW, Cadillac, Chevrolet, Nissan, Mitsubishi, and other auto makers for their electric vehicles.

I can remember visiting local Chevrolet dealers in the earliest days of the Volt extended range electric vehicle and finding the car being offered at a premium price with dealers claiming ignorance of a well-documented low-cost lease option. The Volt met its demise in early 2019 and GM expects to sell a measly 20,000 Bolt EVS annually. It’s hard to get excited about a car when you lose money on every one you sell.

It’s clear that the Bolt is being allocated sparse marketing dollars. I can’t say that I’ve ever seen a television advertisement or a dealer-advertised incentive offer for a Bolt. The vehicle is increasingly looking like a gig-economy fleet offering for the foreseeable future.

Comparing the promotional effort applied to the Mirai by Toyota and the paucity of promotion allotted by the legacy ICE-based vehicle makers for EVs, it is easy to see why Tesla has scampered away with the lion’s share of the EV market and is threatening the sales leadership of traditional ICE-based luxury cars. Car companies are refusing to back up their nascent EV efforts with muscular marketing campaigns.

The latest losers (in the estimation of automotive journalists and some analysts) have been Audi’s E-tron and Jaguar’s I-pace – both posting a few thousand vehicle sales in their first months on the U.S. market in the face of more than 111,000 Tesla Model 3 sales. Alternative propulsion technologies, whether electric or hydrogen-based, remain an awkward talking point for auto makers.

Key takeaways are that car buying decisions remain emotional – not rational. The biggest challenge isn’t making the cars that people want, it is making people want the cars that have been made. Alone among EV auto makers, Tesla appears to be making the cars that people want. It remains one of the few car makers if not the only one struggling to keep pace with advance orders.

The real challenge for Tesla’s EV rivals like General Motors may not be the electrical architecture of their vehicles. It will be rewiring their marketing and dealer networks to support and promote EV-based vehicles.

Advancing Automotive Memory: Development of an 8nm 128Mb Embedded STT-MRAM with Sub-ppm Reliability