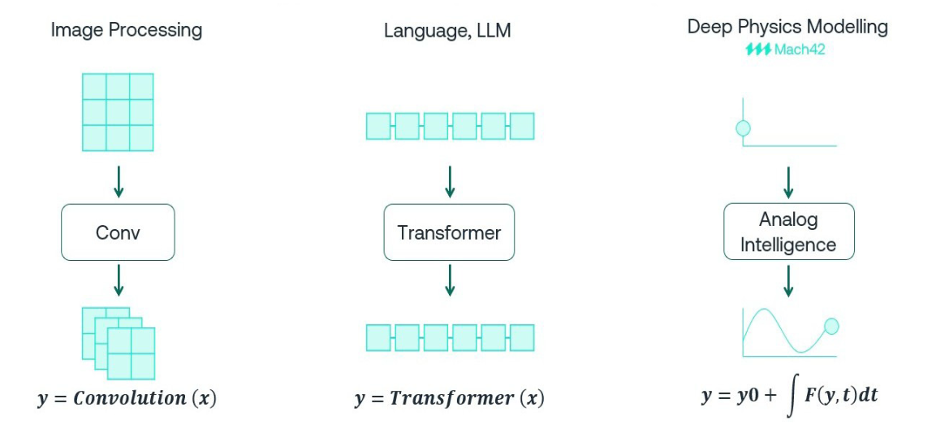

Physical AI is an emerging hot trend, popularly associated with robotics though it has much wider scope than compute systems interacting with the physical world. For any domain in which analysis rests on differential equations (foundational in physics), the transformer-based systems behind LLMs are not the best fit for machine learning. Analog design analysis is a good example. SPICE simulators determine circuit behavior by solving a set of differential equations governed by basic current and voltage laws applied to circuit components together with boundary conditions. Effective learning here requires different approaches.

Machine learning methods in analog

The obvious starting point is to run a bunch of SPICE sims based on some kind of statistical sampling (across parameter and boundary condition variances say) as input to ML training. Monte Carlo analysis is the logical endpoint of this approach. For learning purposes, such methods are effective but significantly time and resource consuming. Carefully reducing samples will reduce runtimes, but what will you miss in-between those samples?

A different approach effectively builds the Newton (-Raphson) iteration method behind SPICE into the training process, enabling automated refinement in gradient-based optimization. (Concerns about correlation with signoff SPICE can be addressed through cross-checks when needed.)

Newton ‘s method is the gold standard in circuit solving but is iterative which could dramatically slow learning without acceleration. Parallelism provided the big breakthrough that launched LLMs to fame. Could the same idea work here? The inherent non-linear nature of analog circuit equations has proven to be a major challenge in effectively using parallelism for real circuits. However a recent paper has introduced an algorithm allowing for machine learning with embedded circuit sim to more fully exploit parallelism using hardware platforms such as GPUs.

Beyond sampling to deep physics modeling

At first glance, simply embedding circuit solving inside a machine learning (ML) algorithm seems not so different from running sims externally then learning from those results. Such a method would still be statistical sampling, packaged in a different way. Mach42 have a different approach in their Discovery Platform which they claim leads to higher accuracy, stability and predictive power in results. I see good reasons to believe their claim.

Brett Larder (co-founder and CTO at Mach42) gave me two hints. First, they aim for continuous time modeling during ML training, whereas most digital methods discretize time. They have observed that conventional methods predict results which are noisy, irregular, even inaccurate, whereas in their algorithm each training point can contain measurements at a different set of time values, rather than requiring that each index on an input/output always correspond to the same time. Training data distributed across timepoints rather than bunched into discretized time steps; I can see how that could lead to more accurate learning.

Second, they aim to learn parameters of the differential equations describing the circuit, rather than learning coarse statistical sampling of input to output results. This is very interesting. Rather than learning to drive a model for statistical interpolation, instead it learns refined differential equations. For me this is intuitively more likely to be robust to changes under different physical conditions and truly feels like deep physics modeling.

The cherry on the cake is that this algorithm can be parallelized to run on a GPU, making training very time-efficient, from SerDes at 2 hours to a complex automotive PMIC at 20 hours, all delivering accuracy at 90% or better. The models produced by this training can run inside SPICE or Verilog-A sims, orders of magnitude faster than classical AMS simulations.

Payoff

Active power management in devices from smartphones to servers depends on LDOs providing regulated power to serve multiple voltage levels. A challenge in designing these circuits is that the transfer function from input to output can shift as current draw and other operating conditions change. Since the goal of an LDO is to provide a stable output, compensating for such shifts is a major concern in LDO design.

The standard approach to characterizing an LDO is to run a bunch of sweeps over circuit parameters to determine how well compensation will manage across a range of load and operating conditions. These simulations consume significant time and resources and can miss potential issues in-between sweep steps. In contrast, the learned dynamic model created by the Discovery Platform provides much more accurate estimation across the range, so that anomalies are much more likely to be detected. Moreover, changes in behavior as parameters are varied can be viewed in real-time thanks to these fast dynamic models.

Very nice – moving beyond transformer-based learning to real physics-based learning. You can read more about this new modelling approach in Mach42’s latest blog HERE.

Also Read:

2026 Outlook with Paul Neil of Mach42

Video EP12: How Mach42 is Changing Analog Verification with Antun Domic

Video EP10: An Overview of Mach42’s AI Platform with Brett Larder

Share this post via:

Comments

There are no comments yet.

You must register or log in to view/post comments.