user nl

Well-known member

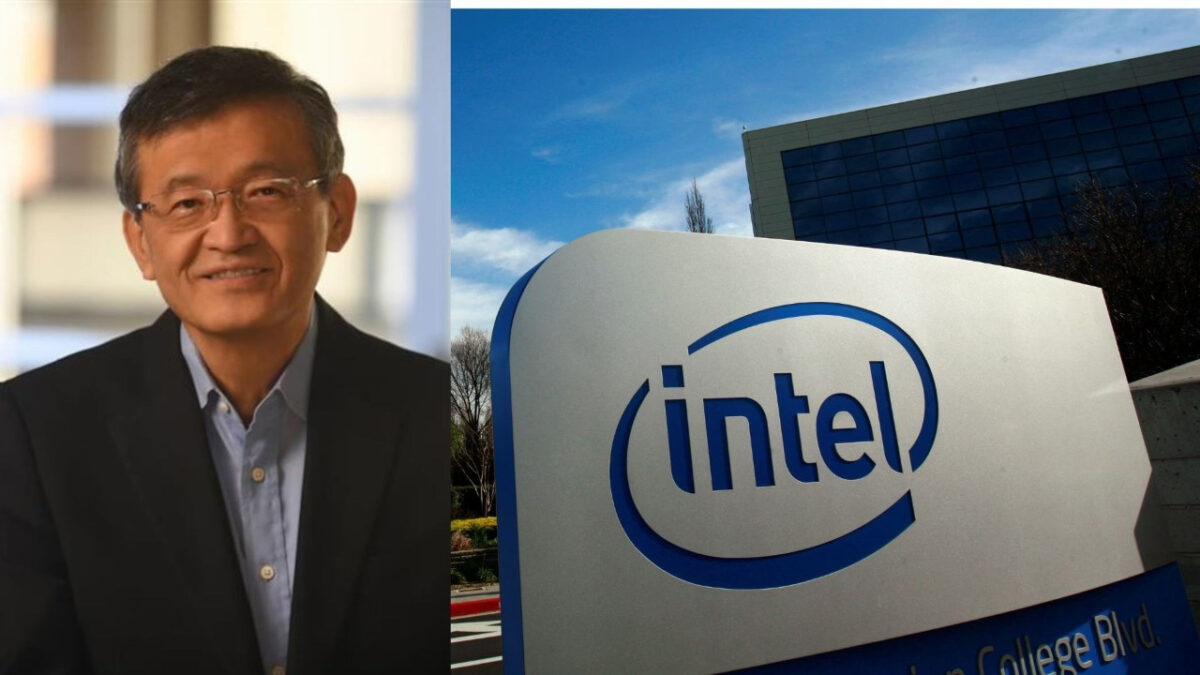

Charlene Barshefsky is a former U.S. Trade Representative. Reed Hundt is a former chair of the FCC. James Plummer is a former Dean of Engineering at Stanford. David B. Yoffie is a professor at Harvard Business School. Ambassador Barshefsky, Mr. Hundt, Professor Plummer, and Professor Yoffie all served as long-time directors on the Intel board.

September 19, 2025 at 4:22 PM EDT

.........................................................................................................................................

Here’s the plan that seems right to us, admittedly from the perspective of outsiders who left Intel’s board some time ago.

First, the government, with support from a consortium of America’s world-leading design firms, should buy all of Intel’s public stock. Nvidia’s $5 billion investment and the subsequent surge in Intel’s stock price suggest that the capital markets would welcome such a move. Some combination of Nvidia, Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Qualcomm, Broadcom, and Google — the best and biggest product design firms on the planet — could easily afford it.

The creation of a successful foundry, drawn from Intel’s manufacturing assets and separated from the design businesses, would be a big win for the Trump administration. It would be even bigger win for the big semiconductor design firms that are otherwise totally dependent on TSMC.

Second, the government and that consortium should find new owners for Intel’s design businesses, including servers and personal computers. Our back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that Intel has left a lot of value locked behind its conglomerate structure. The foundry, for example, has a book value of about $70 billion, but is currently a huge money loser. It needs up to $100 billion in new capital over the next decade to compete with TSMC. The other businesses that could thrive on their own include (1) a microprocessor design business for personal computers, worth somewhere around $100 billion; (2) the design efforts for servers and data centers, also worth potentially $100 billion; (3) the autonomous driving firm, Mobileye, valued at roughly $15. billion; and (4) the extensive venture portfolio, invested in private firms around the world.

Unlocking this value is extraordinarily difficult for a public firm filing quarterly reports. Even in private, the surgery is operationally complicated. Presumably, the board and management cannot see a way forward. Alone, the company cannot raise the money to take the firm private. By itself, it would struggle to obtain the financial, technical and commercial assistance needed to match TSMC. Only the U.S. government would be able to orchestrate the complex, critically important disaggregation of Intel with the necessary participation of the major American design firms.

Third, by going private, Intel can attract the best and brightest talent. With Intel’s competitors flying high on the promise of AI, Intel is suffering from a massive brain drain. As it lays off thousands of employees, the best ones inevitably bail out. The existing public company cannot effectively compete for talent and without talent it is unlikely to succeed in matching TSMC in manufacturing nor make its other units more competitive. Private companies can offer very attractive compensation packages with the promise of a big day when the companies go public again.

The result is that the entire restructuring could be accomplished in roughly a year. That is about as long as the break-up of AT&T took in the 1980s. By 2028, the segments could be sold at handsome prices or taken public with significant returns to private shareholders. Taxpayers could make hundreds of billions of dollars. Not only that, in terms of job creation and national security, the value would be immeasurable.

Naysayers will argue that this strategy is unnecessary. Intel could do it all before, and it can do it all again. But hope is not a strategy, and the world around Intel is not standing still. Naysayers may also argue that Intel should be bought by one of its competitors. Allow Broadcom, for example, to buy Intel and fix it, like it has done with numerous other semiconductor firms. But in today’s environment, an acquisition like this would not fly: China, where Intel sells more than 25% of its products, would never approve it.

Right now, the United States government and Nvidia own a problem. By taking charge of the situation, they can create a tremendous opportunity to do good for the taxpayer. Even more importantly, the break-up of Intel will go a long way to giving the United States the semiconductor ecosystem that underpins every happy scenario for software breakthroughs that benefit the American people and the world.

By Charlene Barshefsky

By Reed Hundt

By James Plummer

By David B. Yoffie

https://fortune.com/2025/09/19/time-for-intel-to-go-private-nvidia-government-trump/

Last edited by a moderator: