Dan Clein

New member

People Management is never black or white, it has many shades of grey…

Too many corporate managers hide behind the policies of the companies they work for, sidestepping growth opportunities in the name of political correctness and opting for an “all-is-business” approach that deprives everyone of greatness. The modern manager needs to act decisively in a global market that rewards the use of knowledge and strategy to make the most of different cultures and geographies. Or better still, when required, managers who can ditch rules altogether and operate off-book.

The Unorthodox Manager introduces a wide-ranging managerial approach that will arm readers with outside-the-box principles that enable “boots on the ground” managers to build their own best methods given any circumstances.. Through a rich professional history filled with an abundance of personal lessons, Dan Clein shares the secrets of managing a modern, multicultural team that gets things done.

This book is hope and inspiration for Human Resources departments, encouraging them to work closely with front line managers in various countries and environments and build policies that encompass different time, location and cultural realities. It will also help companies choose the right hires for management jobs, more accurately valuing staffers who care about people and a company’s long term future over short term business incentives.

If the corporation only measures performance by the way of projects and business deliveries, nobody cares about people. CEOs preach in public or internal meetings, articles, and books that people are the most important asset to a successful company. In reality, management above the director level cares about numbers—and not the number of people hired or promoted, not the number of successful new grads brought in and trained, not the number of people that improved performance as a result of a performance improvement plan. They all review and audit revenues and profit numbers. I was very happy as a first-level manager until I got promoted and was exposed to corporate politics and, yes, the numbers crunch!

Let’s analyze how my unorthodox style results compare to the average, or market standard, for that matter. Based on market data in North America, unwanted attrition (the percentage of people who leave the company that the management did not want to lose) is around 4-6 percent annually. That doubles in India to around 13 percent and gets worse up to 30 percent in cities like Bangalore. My record is 0 percent unwanted attrition for twenty years. Why? someone might ask. Because I’ve spent time and energy finding the issues my team members had to deal with, helping them solve them, and making sure they succeed. I’ve invested effort and many outside work hours meeting families and learning about employees’ struggles, so when needed, I knew how to help. When they wanted change, if I thought it was a positive move, I would help them and be their reference for the new job. This made them trust that if they came to ask for help, I would be there. . .. Some are still asking for help or advice, twenty years later.

This book provides the reader with a collection of experiences and verified solutions for successful people management. Hopefully, I can energize and help you go beyond company policies, political correctness, and the priority of the “bottom line,” and start focusing on your team’s (employees’) success. Personally, I believe that even the poorest performer can become a star with personal investment in energy and motivation. The job of a manager is to find the solutions that drive their employees to their best performance. Employees and professional friends alike have pointed out that my style is not in line with “standard business practices,” but I’ve proven, in twenty-plus years of managing people, that my team always delivers, and so have been viewed as an example of success.

I started by managing a team of five people at MOSAID (a small memory design house in Ottawa, Canada) in 1991. There were no schools providing fresh new grads with layout knowledge then, so I had to find “out-of-the-box” solutions to grow the team to ten by 1996. When I joined PMC-Sierra (a company with headquarters in Vancouver, Canada) in December 1999, I inherited five people there. My mandate was to grow the team based on the corporation’s growth needs, so I grew it to thirty-five people all around the world. From a single location in Canada to three in Canada, one in the US, one in Israel, and one in India. I had to learn how to deal with time zones, improve my video and email communication, and understand all kinds of different cultures and religions. I had Chinese, Arabs, Christians, Jews, Hindu, etc., on my team. The majority were women, and they never had issues with salary differences (because they did not exist in my teams) or any bias due to sex or religion. Some of the members of my team were internally trained, some came with knowledge and we had to add to their knowledge, but all had to be introduced to our team flows and procedures. Like in any operation, we made some mistakes on the way to success, and I will share those also.

This book reveals what made me the person I am in my professional life, and why in many cases I was not afraid to step outside of corporate standards or values.

Before we talk about first-line management (my personal sweet spot for management), let’s define the difference between a technical leader and a manager, in Dan Clein’s opinion. I always like to clarify concepts before going into methodologies, so here is my description.

We have a team of ten people that needs to pass a jungle. The technical leader is the individual who climbs a tree to make an informed decision on where to go and how to get there. The decision is based on their knowledge, experience, and the data gathered from the treetop. The technical leader comes down and “sells” to the team what has to be done and starts chopping the vegetation forward, followed by the team. The technical leaders open the path. They have a vision and energy, like to take risks, can easily assess situations, and communicate very well with the team.

The manager, on the other hand, is the one who stays behind and ensures that the team has sharp machetes, food, supplies, and clothing to reach their goal. If needed, the manager will hire additional people based on the feedback from the technical leader. Communication back and forth between the technical leader and manager is the priority. They have to have a very good understanding of each other’s goals and priorities, and—obviously—TRUST. The team’s success depends on its members’ ability to perform, but mostly on the coordination between the technical leader and manager. Technical leaders and managers prepare the team for success together.

Based on my experience, technical leaders can make good managers when they get a little seasoned, if they keep some “exciting” but low-priority technical activities for fun. Managers need time to deal with team issues, from growth to shrinkage, so they need allocated time for people management. In many companies, the managers still have hands-on technical project activities, and this lowers their “people management” involvement and priorities. The main reason for poor management is that, in too many cases, good technical leaders get promoted to managers when successful. However, their interests and priorities are not people, but tasks, technology, and products, so they fail to make the team successful. They can be trained and mentored, but at the end of the day, we all give priority to our personal goals. Companies who understand this differentiation will offer top performers different paths for growth. For people who like to build and manage teams, that would be a path to manager, director, VP, etc. For others interested in staying in the technical world, the path would be to technical advisor (TA), principal engineer (PE), and fellow (F).

What does “fresh blood” mean, in management?

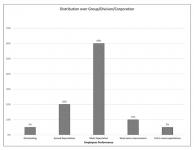

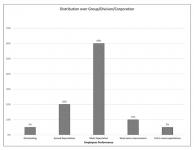

Unfortunately, aggressive companies decided that “performance management” (another book I have in progress) can be solved simply by methodology, so if you want to keep your team “motivated,” you have to refresh the talent pool all the time. In North America, Cisco socialized a bell curve for that with the idea that, every year, the bottom performers have to be let go. Here is the example:

If you analyze the graph, you see that, in principle, every year the company should let go at least 5 percent of the workforce and replenish it with “fresh blood.” In their opinion, this way, everybody is motivated to perform, as their job depends on their personal and team performance. This is what they said, but I have another theory: this was invented by an HR executive to ensure their department was busy all the time with the simpler tasks of recruiting and firing rather than the hard work of helping people grow and improve performance. This thinking prioritizes business success rather than human success, even though the department is called human resources. As a manager, you will have to walk a thin line between the two priorities.

I never adhered to this theory because I believe that each team, like each army, needs many ranks, from soldiers to generals and everything in between. Each project has tasks that require imagination and energy, but also tasks that are repetitive and simple. If you use your superstars on the simple or mundane tasks, they will automate as much as possible and then leave the team/company for more challenging positions. If you only have “soldiers,” you cannot tackle complex projects or challenging activities with tight schedules and deliveries. From my experience, you need both, including a few intermediate levels in between.

I believe that teams will produce what is required, if the conditions to do so are provided. And that’s not only money and tools or measurements, but people. They may have good and bad days, they may have family priorities to deal with, and you as a manager have to take all these into consideration. Nobody lives their life for a company’s growth and glory, though some executives would like to believe they do. The reality is that executives are motivated by recognition and money, and these come from company performance.

The problems with these standard measurements are many, but the worst is that if you don’t have any poor performers (because you had to clean the team last year and had no new hires), and the company mandates that the bottom 5 percent heads out, you will have to let good people go. Maybe at the corporate level the 5 percent is a nice-to-have goal, but some companies are enforcing this as a rule, some first- and second-rank managers obey it, and you get the worst of this partially good idea... Managers will downgrade people from meet expectations to need improvements so they can make the quota. If the team is too small—ten people, for example—the loss is almost irreplaceable. This is not people management. This is “project management,” applied to humans, where the deliveries are “bottom-line” costs. Try to get the top-line back up later.

I always asked HR departments and never received the cost analysis of replacing a solid contributor who is leaving because they’re unhappy versus the 5 percent rule implementation. We know how much somebody costs (salary + overhead) and how much their “business value” is to the company (at least two times that), but nobody provides the cost of losing this person on projects for three to six months, the cost of recruiting new people, and the ramp-up time/cost to bring new people to the same level of performance and comfort inside the organization or team. Based on my personal cost analysis and public domain data, this is a big negative number, but companies do not measure it. If they did, people managers should be measured based on “unwanted” attrition numbers. Unwanted attrition is the percentage of people who leave the company that the management did not want to leave. We are talking about star and solid contributors here. We have “wanted attrition”—people with low performance who will never reach team standards—people who we have to let go. Maybe the technology complexity is beyond their capabilities, or we made a mistake in hiring them in the first place.

There is also the natural attrition, when people retire or the company moves location or changes its profile, such that their specialties are not needed anymore. To build a good performance team, you have to start with hiring the right people, managing their growth and performance, and making them shine. In some cases, I had to send people away, as my team was not capable of providing the challenges some individuals were interested in taking on, or whom I thought weren’t ready for them. We know that 90 percent of people change companies because of their direct manager, so why not spend the time and effort choosing the right people for management and training them?

If you want to learn more feel free to read my book… Here is how to get it:

https://www.theunorthodoxmanager.com/

Dan Clein

www.comet-ic.com

www.comet-ic.com

Too many corporate managers hide behind the policies of the companies they work for, sidestepping growth opportunities in the name of political correctness and opting for an “all-is-business” approach that deprives everyone of greatness. The modern manager needs to act decisively in a global market that rewards the use of knowledge and strategy to make the most of different cultures and geographies. Or better still, when required, managers who can ditch rules altogether and operate off-book.

The Unorthodox Manager introduces a wide-ranging managerial approach that will arm readers with outside-the-box principles that enable “boots on the ground” managers to build their own best methods given any circumstances.. Through a rich professional history filled with an abundance of personal lessons, Dan Clein shares the secrets of managing a modern, multicultural team that gets things done.

This book is hope and inspiration for Human Resources departments, encouraging them to work closely with front line managers in various countries and environments and build policies that encompass different time, location and cultural realities. It will also help companies choose the right hires for management jobs, more accurately valuing staffers who care about people and a company’s long term future over short term business incentives.

If the corporation only measures performance by the way of projects and business deliveries, nobody cares about people. CEOs preach in public or internal meetings, articles, and books that people are the most important asset to a successful company. In reality, management above the director level cares about numbers—and not the number of people hired or promoted, not the number of successful new grads brought in and trained, not the number of people that improved performance as a result of a performance improvement plan. They all review and audit revenues and profit numbers. I was very happy as a first-level manager until I got promoted and was exposed to corporate politics and, yes, the numbers crunch!

Let’s analyze how my unorthodox style results compare to the average, or market standard, for that matter. Based on market data in North America, unwanted attrition (the percentage of people who leave the company that the management did not want to lose) is around 4-6 percent annually. That doubles in India to around 13 percent and gets worse up to 30 percent in cities like Bangalore. My record is 0 percent unwanted attrition for twenty years. Why? someone might ask. Because I’ve spent time and energy finding the issues my team members had to deal with, helping them solve them, and making sure they succeed. I’ve invested effort and many outside work hours meeting families and learning about employees’ struggles, so when needed, I knew how to help. When they wanted change, if I thought it was a positive move, I would help them and be their reference for the new job. This made them trust that if they came to ask for help, I would be there. . .. Some are still asking for help or advice, twenty years later.

This book provides the reader with a collection of experiences and verified solutions for successful people management. Hopefully, I can energize and help you go beyond company policies, political correctness, and the priority of the “bottom line,” and start focusing on your team’s (employees’) success. Personally, I believe that even the poorest performer can become a star with personal investment in energy and motivation. The job of a manager is to find the solutions that drive their employees to their best performance. Employees and professional friends alike have pointed out that my style is not in line with “standard business practices,” but I’ve proven, in twenty-plus years of managing people, that my team always delivers, and so have been viewed as an example of success.

I started by managing a team of five people at MOSAID (a small memory design house in Ottawa, Canada) in 1991. There were no schools providing fresh new grads with layout knowledge then, so I had to find “out-of-the-box” solutions to grow the team to ten by 1996. When I joined PMC-Sierra (a company with headquarters in Vancouver, Canada) in December 1999, I inherited five people there. My mandate was to grow the team based on the corporation’s growth needs, so I grew it to thirty-five people all around the world. From a single location in Canada to three in Canada, one in the US, one in Israel, and one in India. I had to learn how to deal with time zones, improve my video and email communication, and understand all kinds of different cultures and religions. I had Chinese, Arabs, Christians, Jews, Hindu, etc., on my team. The majority were women, and they never had issues with salary differences (because they did not exist in my teams) or any bias due to sex or religion. Some of the members of my team were internally trained, some came with knowledge and we had to add to their knowledge, but all had to be introduced to our team flows and procedures. Like in any operation, we made some mistakes on the way to success, and I will share those also.

This book reveals what made me the person I am in my professional life, and why in many cases I was not afraid to step outside of corporate standards or values.

Before we talk about first-line management (my personal sweet spot for management), let’s define the difference between a technical leader and a manager, in Dan Clein’s opinion. I always like to clarify concepts before going into methodologies, so here is my description.

We have a team of ten people that needs to pass a jungle. The technical leader is the individual who climbs a tree to make an informed decision on where to go and how to get there. The decision is based on their knowledge, experience, and the data gathered from the treetop. The technical leader comes down and “sells” to the team what has to be done and starts chopping the vegetation forward, followed by the team. The technical leaders open the path. They have a vision and energy, like to take risks, can easily assess situations, and communicate very well with the team.

The manager, on the other hand, is the one who stays behind and ensures that the team has sharp machetes, food, supplies, and clothing to reach their goal. If needed, the manager will hire additional people based on the feedback from the technical leader. Communication back and forth between the technical leader and manager is the priority. They have to have a very good understanding of each other’s goals and priorities, and—obviously—TRUST. The team’s success depends on its members’ ability to perform, but mostly on the coordination between the technical leader and manager. Technical leaders and managers prepare the team for success together.

Based on my experience, technical leaders can make good managers when they get a little seasoned, if they keep some “exciting” but low-priority technical activities for fun. Managers need time to deal with team issues, from growth to shrinkage, so they need allocated time for people management. In many companies, the managers still have hands-on technical project activities, and this lowers their “people management” involvement and priorities. The main reason for poor management is that, in too many cases, good technical leaders get promoted to managers when successful. However, their interests and priorities are not people, but tasks, technology, and products, so they fail to make the team successful. They can be trained and mentored, but at the end of the day, we all give priority to our personal goals. Companies who understand this differentiation will offer top performers different paths for growth. For people who like to build and manage teams, that would be a path to manager, director, VP, etc. For others interested in staying in the technical world, the path would be to technical advisor (TA), principal engineer (PE), and fellow (F).

What does “fresh blood” mean, in management?

Unfortunately, aggressive companies decided that “performance management” (another book I have in progress) can be solved simply by methodology, so if you want to keep your team “motivated,” you have to refresh the talent pool all the time. In North America, Cisco socialized a bell curve for that with the idea that, every year, the bottom performers have to be let go. Here is the example:

If you analyze the graph, you see that, in principle, every year the company should let go at least 5 percent of the workforce and replenish it with “fresh blood.” In their opinion, this way, everybody is motivated to perform, as their job depends on their personal and team performance. This is what they said, but I have another theory: this was invented by an HR executive to ensure their department was busy all the time with the simpler tasks of recruiting and firing rather than the hard work of helping people grow and improve performance. This thinking prioritizes business success rather than human success, even though the department is called human resources. As a manager, you will have to walk a thin line between the two priorities.

I never adhered to this theory because I believe that each team, like each army, needs many ranks, from soldiers to generals and everything in between. Each project has tasks that require imagination and energy, but also tasks that are repetitive and simple. If you use your superstars on the simple or mundane tasks, they will automate as much as possible and then leave the team/company for more challenging positions. If you only have “soldiers,” you cannot tackle complex projects or challenging activities with tight schedules and deliveries. From my experience, you need both, including a few intermediate levels in between.

I believe that teams will produce what is required, if the conditions to do so are provided. And that’s not only money and tools or measurements, but people. They may have good and bad days, they may have family priorities to deal with, and you as a manager have to take all these into consideration. Nobody lives their life for a company’s growth and glory, though some executives would like to believe they do. The reality is that executives are motivated by recognition and money, and these come from company performance.

The problems with these standard measurements are many, but the worst is that if you don’t have any poor performers (because you had to clean the team last year and had no new hires), and the company mandates that the bottom 5 percent heads out, you will have to let good people go. Maybe at the corporate level the 5 percent is a nice-to-have goal, but some companies are enforcing this as a rule, some first- and second-rank managers obey it, and you get the worst of this partially good idea... Managers will downgrade people from meet expectations to need improvements so they can make the quota. If the team is too small—ten people, for example—the loss is almost irreplaceable. This is not people management. This is “project management,” applied to humans, where the deliveries are “bottom-line” costs. Try to get the top-line back up later.

I always asked HR departments and never received the cost analysis of replacing a solid contributor who is leaving because they’re unhappy versus the 5 percent rule implementation. We know how much somebody costs (salary + overhead) and how much their “business value” is to the company (at least two times that), but nobody provides the cost of losing this person on projects for three to six months, the cost of recruiting new people, and the ramp-up time/cost to bring new people to the same level of performance and comfort inside the organization or team. Based on my personal cost analysis and public domain data, this is a big negative number, but companies do not measure it. If they did, people managers should be measured based on “unwanted” attrition numbers. Unwanted attrition is the percentage of people who leave the company that the management did not want to leave. We are talking about star and solid contributors here. We have “wanted attrition”—people with low performance who will never reach team standards—people who we have to let go. Maybe the technology complexity is beyond their capabilities, or we made a mistake in hiring them in the first place.

There is also the natural attrition, when people retire or the company moves location or changes its profile, such that their specialties are not needed anymore. To build a good performance team, you have to start with hiring the right people, managing their growth and performance, and making them shine. In some cases, I had to send people away, as my team was not capable of providing the challenges some individuals were interested in taking on, or whom I thought weren’t ready for them. We know that 90 percent of people change companies because of their direct manager, so why not spend the time and effort choosing the right people for management and training them?

If you want to learn more feel free to read my book… Here is how to get it:

https://www.theunorthodoxmanager.com/

Dan Clein

CoMeT-IC Consulting

Concepts, Methodologies & Tools for IC Design & Performance Management